✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Grief

The crime thriller is often mistakenly viewed as a puzzle box—a mechanism of clues, red herrings, and eventual revelations designed to satisfy our intellectual vanity. But in the hands of a director like Ying-Ting Tseng, the genre becomes something far more permeable and aching. In *The Abandoned* (2023), the mystery of a mutilated corpse is not merely a whodunit; it is a structural survey of a society that has decided certain lives—and certain sorrows—are invisible.

The film opens with a sequence that serves as a thesis statement for the entire narrative. On New Year's Eve, amidst the explosive joy of fireworks, we find Detective Wu Jie (a hollowed-out Janine Chang) sitting in her car, a service pistol pressed under her chin. She is a woman attempting to exit a world that has already ended for her following the suicide of her fiancé. She is interrupted not by a savior, but by the discovery of a corpse—a Thai migrant woman, washed ashore without a heart or a ring finger. This juxtaposition is crucial: Wu Jie is saved from death only by the intrusion of death. It suggests that her penance, or perhaps her path to understanding her own grief, lies in witnessing the grief of others.

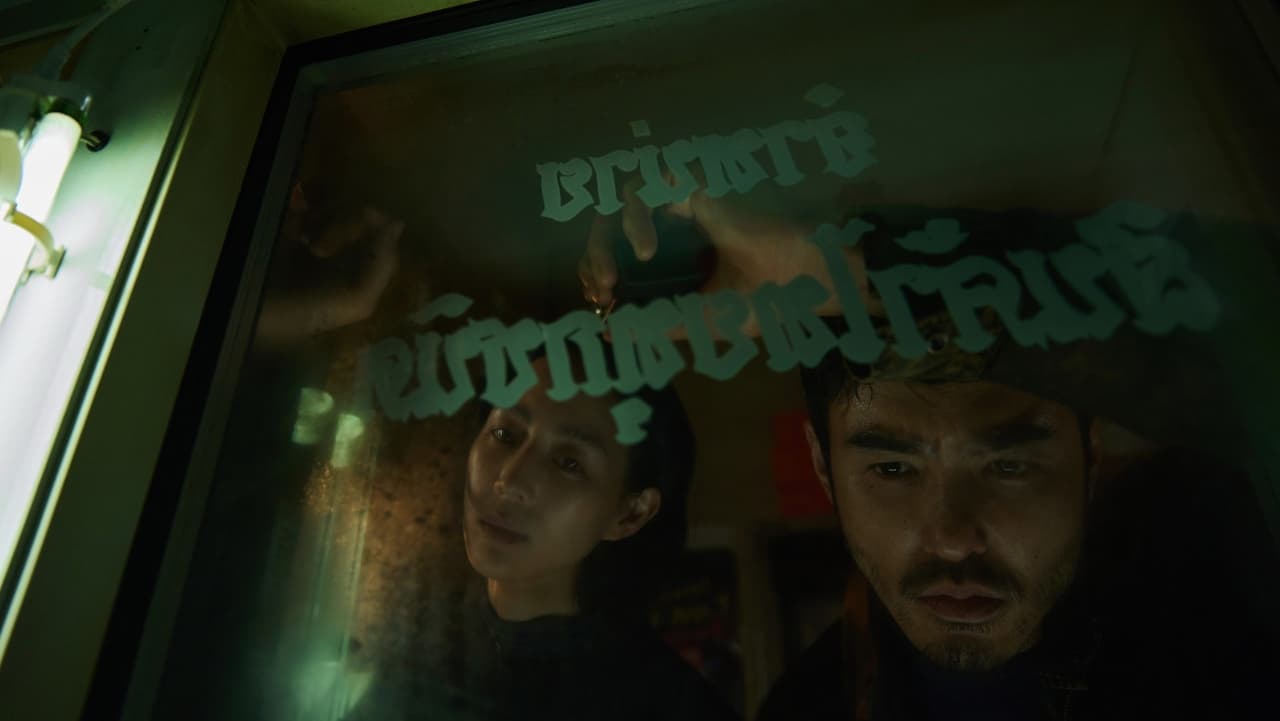

Tseng, stepping confidently into feature filmmaking after his socially conscious TV work, drenches the film in a neo-noir aesthetic that feels suffocatingly wet and cold. The cinematography does not just capture Taipei; it captures the shadows of Taipei. The camera lingers on the forgotten corners—the illegal factories, the damp alleyways, and the riverbanks where the city spits out what it refuses to digest. This visual language serves the film’s dual focus: the "abandoned" are not just the lovers left behind by suicide or murder, but the Southeast Asian migrant workers who power Taiwan’s economy while remaining legally and socially spectral.

The procedural elements of the film are competent, involving a rookie partner and a morally grey broker (Ethan Juan), but the film’s true power lies in its thematic mirroring. The killer and the detective are terrifyingly similar architects of pain; both are defined by an inability to process the departure of a loved one. While the killer tries to preserve "love" through grisly anatomical trophies—literalizing the metaphor of giving someone your heart—Wu Jie tries to preserve her connection to her fiancé by remaining in the stasis of her own depression.

Where many serial killer films devolve into a glorification of the villain's intellect, *The Abandoned* remains steadfastly humanistic. It argues that the true horror is not the violence committed by a single psychopath, but the systemic indifference that allows women to vanish without a ripple. The victims are targeted not just because they are vulnerable, but because they are culturally illegible to the majority.

Ultimately, *The Abandoned* transcends the limitations of the police procedural. It is less interested in the satisfaction of handcuffs clicking shut than in the quiet, devastating realization that survival is a choice one must make daily. The film concludes not with a triumph of law and order, but with a weary, necessary acceptance that while we cannot bring back the dead, we can choose not to join them just yet.