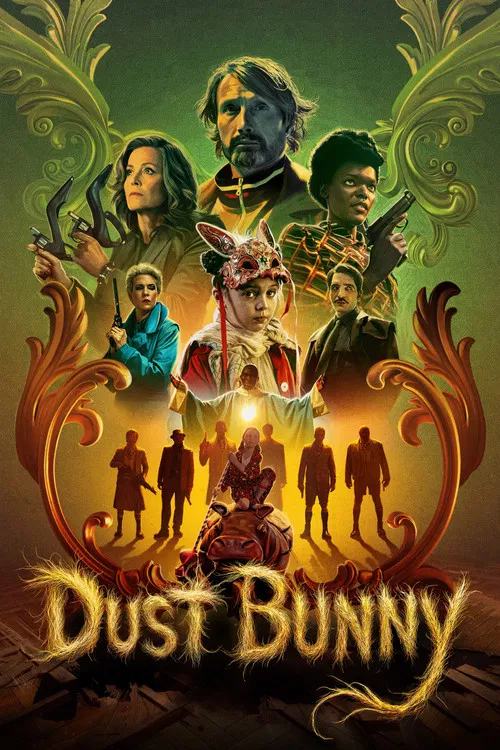

The Teeth in the FluffThere is a moment early in Bryan Fuller’s *Dust Bunny* where the camera, trapped in an aggressive, anxiety-inducing 3:1 aspect ratio, lingers on the floorboards of a ten-year-old’s bedroom. We are waiting for a jump scare, conditioned by decades of "monster under the bed" tropes to expect a claw or a glowing eye. Instead, Fuller gives us something far more unsettling: silence, dust, and the crushing weight of a child’s unheard trauma. For his feature directorial debut, Fuller—the visual maximalist behind television’s *Hannibal* and *Pushing Daisies*—has crafted a film that is ostensibly a "gateway horror" fable but operates more profoundly as a meditation on the protective lies adults tell children, and the violent truths children tell themselves to survive.

The premise reads like a bedtime story scribbled by a feverish Grimm brother. Aurora (a revelation in Sophie Sloan) is convinced a literal dust bunny—a sentient, carnivorous accumulation of neglect living under her bed—has devoured her family. Her solution is pragmatic rather than panicked: she hires her neighbor (Mads Mikkelsen), a hitman she has observed from afar, to kill it. What follows is not merely an odd-couple action comedy, though it certainly wears those clothes with style. It is a collision of two lonely worlds. Mikkelsen, shedding the sophisticated cruelty of Hannibal Lecter for a weary, tactile tenderness, plays the hitman not as a cool professional, but as a man whose violence is a heavy coat he is too tired to take off.

Fuller’s visual language here is suffocatingly beautiful. He rejects the standard widescreen format for a letterbox strip that mimics the human field of vision when hiding—peering through the crack of a closet door or over the edge of a blanket. This claustrophobia forces us to look at the textures of Aurora’s world: the peeling wallpaper that seems to breathe, and the saturated, candy-colored lighting that suggests a reality warping under emotional pressure. It is a visual landscape that feels like *Amélie* directed by John Carpenter, where whimsy is the only defense against the grotesque.

The heart of the film, however, is not the creature effects (which oscillate intentionally between terrifying and Jim Henson-esque absurdity), but the unspoken pact between Aurora and her neighbor. The film’s "conversation" has largely focused on its genre-bending audacity, but the real alchemy is in how Fuller treats the monster. Is it real? Is it a manifestation of grief? The film refuses to cheapen Aurora’s experience by fully committing to either until it hurts. When the violence erupts—and it does, with a balletic brutality that recalls the best of Hong Kong cinema—it feels like an externalization of Aurora’s internal chaos. Mikkelsen defends her from human assassins and supernatural dust alike, validating her fears in a way no other adult has. He doesn't just protect her; he *believes* her.

*Dust Bunny* is imperfect; its third act struggles to reconcile its emotional stakes with the mechanics of a creature feature showdown. Yet, in an era of cinema dominated by algorithmic safety, Fuller offers a jagged, handmade jewel. He understands that for a child, the difference between a monster and a memory is negligible—both can eat you alive if you let them. By the time the credits roll, we realize this wasn't a story about killing a monster. It was a story about finding someone willing to hold the flashlight while you look underneath the bed.