✦ AI-generated review

The Ecstasy of Excess

Martin Scorsese has spent half a century chronicling the American appetite for self-destruction, usually through the eyes of men who want the world and are willing to burn it down to get it. If *Goodfellas* was an examination of blue-collar gangsterism and *Casino* the dissection of corporate mob rule, then *The Wolf of Wall Street* (2013) is the director’s final, manic thesis on the spiritual rot of capitalism itself. It is a film that does not merely depict greed; it inhales it, snorts it, and dares the audience to enjoy the high before revealing the inevitable crash.

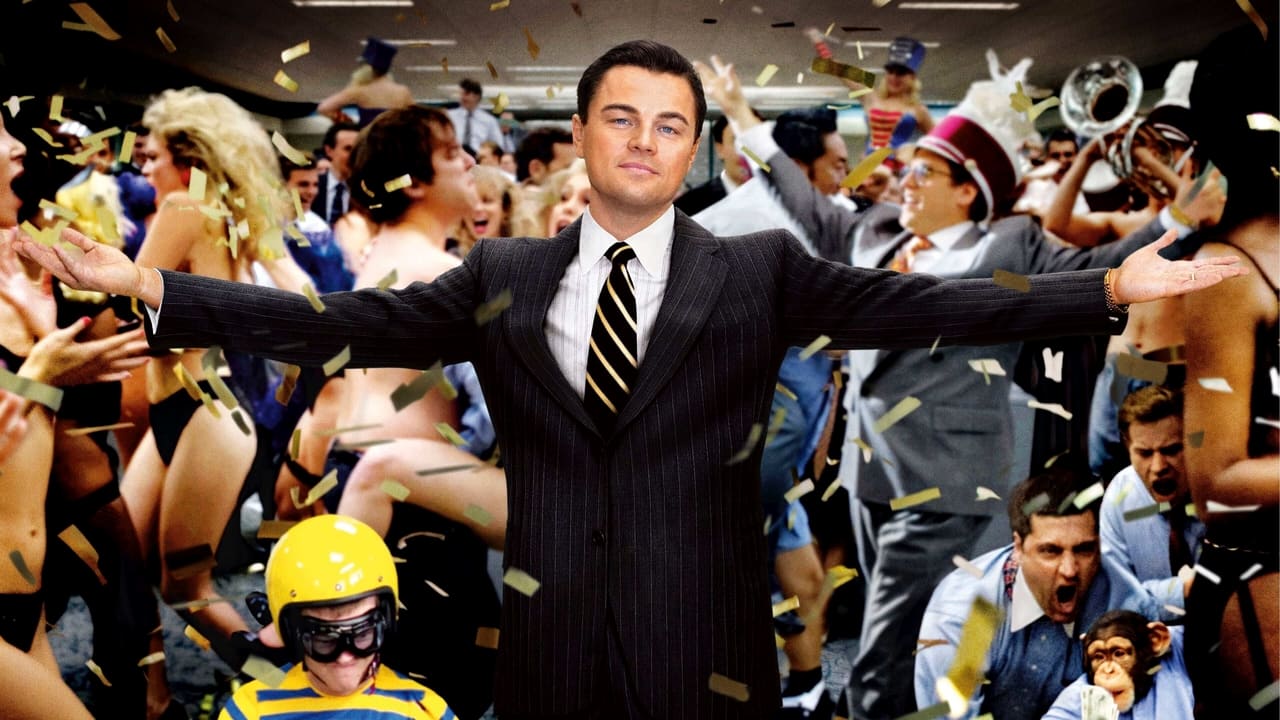

Scorsese and screenwriter Terence Winter frame the saga of Jordan Belfort not as a cautionary tale, but as a kinetic, three-hour bacchanal. The visual language is deliberately exhausting, mirroring the drug-fueled stamina of its protagonist. Editor Thelma Schoonmaker cuts the film with a rhythmic aggression that mimics a heartbeat spiking on cocaine, refusing to let the viewer breathe or look away. This is most evident in the film’s centerpiece sequence: the "Cerebral Palsy" phase of the Quaalude overdose. Here, Scorsese strips Belfort of his verbal weapons—his primary superpower—and reduces him to a prehistoric creature dragging his body toward a Lamborghini. It is a moment of supreme physical comedy that rivals the silent era's slapstick, yet it is underscored by a terrifying reality: this man is willing to die, and kill, to maintain his grip on his empire.

At the center of this storm is Leonardo DiCaprio, who delivers a performance of feral intensity. He sheds the brooding weight of his dramatic roles to play Belfort as a charismatic monster, a man whose charm is as lethal as it is infectious. The genius of the performance—and the film—lies in the breaking of the fourth wall. When Belfort speaks directly to the camera, he is not just narrating; he is recruiting. He treats the audience as his co-conspirators, explaining the mechanics of the con with a wink, assuming we are just as hungry for the easy money as he is.

This complicity is where the film drew its sharpest criticism, with detractors arguing that Scorsese glamorized the depravity he sought to critique. However, to demand a clear moral lecture from Scorsese is to misunderstand his art. He refuses to act as the viewer’s conscience. Instead, he presents the seduction of wealth in all its gaudy, naked glory, trusting us to see the hollowness beneath. He shows us the cost—the destroyed families, the endangered children, the complete erosion of the soul—but he never pauses the party to scold the guests.

The film’s true verdict arrives in its final, haunting shot. Belfort, stripped of his fortune but not his nature, stands before a seminar of eager, wide-eyed hopefuls. He asks them the same question he asked his first disciples: "Sell me this pen." As the camera tracks over the audience, we do not see disgusted faces turning away from a convicted criminal. We see desperation. We see envy. We see a sea of people waiting for the next wolf to lead them. Scorsese leaves us with the uncomfortable realization that Jordan Belfort is not an aberration of the system, but a reflection of a society that values the sale above the soul. The tragedy is not that men like Belfort exist, but that we keep buying what they are selling.