The Embers of a Dying MythThe Western has never truly died; it merely learned to disguise itself. Sometimes it wears the chrome of a post-apocalyptic wasteland, other times the kevlar of a modern tactical thriller. In *Hellfire*, director Isaac Florentine strips away the disguise, returning us to the genre’s skeletal remains—a lone stranger, a corrupt town, and the inevitable purgative violence. Yet, beneath the bullet casings and the bruised knuckles of its septuagenarian protagonist, this film is not just an action vehicle; it is a meditation on the exhaustion of the American mythos, embodied by a hero who looks less like a savior and more like a ghost who forgot to fade away.

Florentine, a craftsman revered in the cult circles of martial arts cinema for his balletic precision in films like *Undisputed II*, here trades his usual kinetic freneticism for something heavier, almost geological. The film does not sprint; it trudges, mirroring the weary gait of its lead.

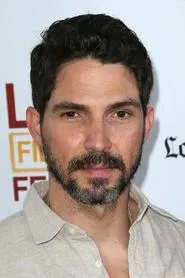

Visually, *Hellfire* is suffocated by the heat of its own title. The cinematography by Ross W. Clarkson favors a palette of scorched earth and rusted metal, creating a world that feels pre-apocalyptic. The town of Rondo is not a community but a cage, ruled by the grotesque Jeremiah (Harvey Keitel) and his enforcer Sheriff Wiley (Dolph Lundgren). Florentine frames these villains not as masterminds, but as symptoms of a rotting system—men who have mistaken cruelty for power.

The film’s aesthetic success lies in its refusal to glamorize this decay. When violence erupts, as it must, it is not the smooth, choreographed dance of Florentine’s earlier work. It is messy, desperate, and ugly. The sound design emphasizes the crunch of bone and the wheeze of breath over the sleek "pew-pew" of suppressed pistols, grounding the action in a fragile mortality that defies the genre’s usual invincibility.

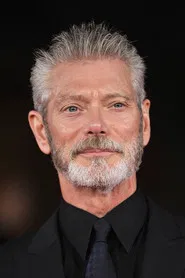

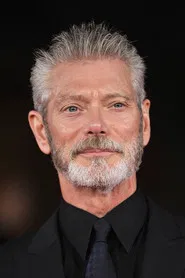

At the center of this scorched landscape is Stephen Lang, an actor of granite resolve and eyes that seem to have witnessed the burning of libraries. As the nameless Drifter—later dubbed "Nomada"—Lang delivers a masterclass in physical silence. He is the antithesis of the modern superhero; he is not saving the world, he is barely saving himself.

The film’s "heart" is located in the unspoken dialogue between Lang’s body and the space he inhabits. Watch the scene where he first enters the local diner. He doesn't swagger; he occupies the room with the reluctance of a man who knows his mere presence is a catalyst for trouble. The script, sparse and archetypal, relies on Lang to convey decades of trauma through posture alone. His confrontation with Lundgren’s sheriff is not a clash of titans, but a meeting of two relics—one who has chosen to uphold corruption to survive, and one who has chosen to destroy it to atone. It is "dad cinema" elevated to Greek tragedy, questioning the utility of violence in a world that no longer remembers why the war started.

Ultimately, *Hellfire* transcends its direct-to-video DNA by embracing the melancholy of its existence. It is not trying to launch a franchise or sell toys. It is a story about the end of things—the end of the frontier, the end of the "tough guy" era, and the end of the illusion that a good man with a gun can fix a broken society. Isaac Florentine has crafted a eulogy with a pulse, reminding us that sometimes the fire doesn't cleanse; it just reveals the hardness of what remains. In a cinema landscape obsessed with youth and multiverses, there is something profoundly grounding in watching an old man simply try to set one small corner of the world right, before the darkness takes him too.