The Architecture of SleepThere is a pervasive lie in modern American animation, a glossy commandment that has replaced the fairy tales of old: *If you dream it, it will come true.* It is a comforting opiate for a generation raised on algorithmically generated hope, but it is rarely honest. Alex Woo’s directorial debut, *In Your Dreams*, dares to dismantle this doctrine. It suggests that the waking world, with all its sharp edges and disappointments, is not a prison to escape, but the only place where life actually happens.

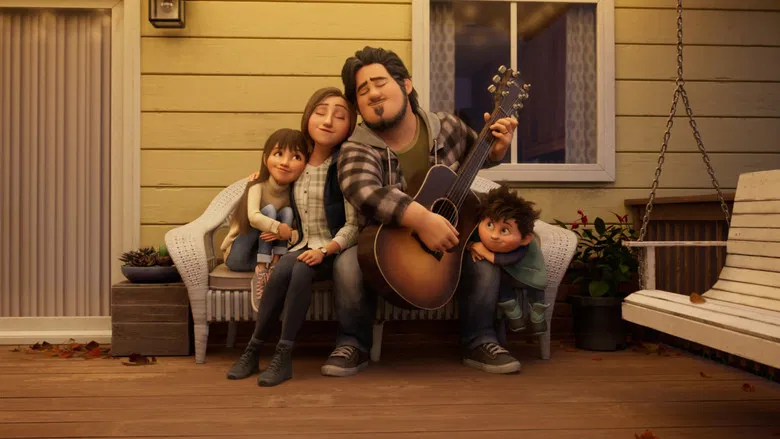

Woo, a veteran of Pixar’s story department, understands that the most effective children’s cinema is often a Trojan horse for adult anxieties. On the surface, the film is a kinetic, candy-colored odyssey about two siblings—Stevie (Jolie Hoang-Rappaport), a neurotic perfectionist, and her brother Elliot (Elias Janssen), an agent of pure chaos—journeying into the subconscious to save their parents’ crumbling marriage. But beneath the slapstick of zombie breakfast foods and plush giraffe guides lies a profound melancholy about the impotence of children in the face of adult failure.

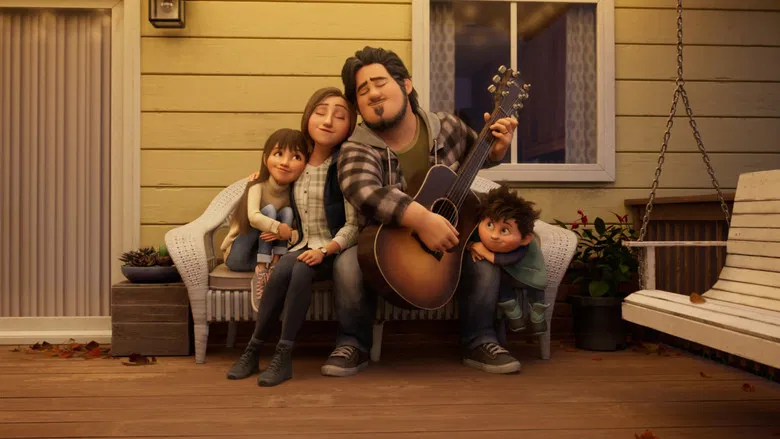

The visual language of *In Your Dreams* is a study in dichotomy. The "real world" is rendered with a tactile, almost suffocating grounding; you can practically smell the stale air of a household bracing for divorce. When the children cross the threshold into the dreamscape, however, the film unzips its own reality. Woo and co-director Erik Benson utilize a shifting aesthetic that moves from 3D stability to 2D anime-inspired fluidity, mirroring the instability of the dreaming mind.

This is not merely aesthetic flexing; it is narrative function. The dream world is seductive because it is malleable, a place where Stevie can edit out her brother’s annoying tendencies or script her parents’ reconciliation. The animation becomes looser, wilder, and more vibrant the further they travel from the truth. Yet, the film’s most striking visual achievement is how it allows the grotesque to bleed into the whimsical. The nightmare sequences are not just scary; they are psychologically specific, manifesting the characters' dread of abandonment in ways that feel genuinely dangerous.

At its heart, the film rests on the fragile chemistry between Stevie and Elliot. The "bickering siblings" trope is well-worn territory, but the script treats their friction as a symptom of their shared trauma rather than a plot device. Stevie’s desire for a "perfect family"—the wish she intends to drag to the Sandman—is revealed to be a toxic fantasy. The film bravely argues that the pursuit of perfection is often a rejection of love.

The voice performances, particularly from Simu Liu and Cristin Milioti as the parents, provide a necessary anchor. They are not villains, nor are they oblivious buffoons; they are simply people who have run out of road. By grounding the parents' conflict in recognizable, quiet tragedy, the film raises the stakes of the children’s magical journey. We know, even if Stevie doesn't, that no amount of magic dust can fix a fundamental incompatibility.

*In Your Dreams* ultimately lands on a verdict that feels revolutionary for its genre: Dreams are a distraction. In a cinematic landscape that constantly tells children to retreat into fantasy to solve their problems, Woo’s film gently guides them back to the dinner table, messy and broken as it may be. It posits that while dreams are a nice place to visit, we cannot live there. The resolution is not a magical fix, but an acceptance of the beautifully fractured reality of being a family. It is a mature, bittersweet lesson wrapped in the guise of a Saturday morning adventure, proving that sometimes, waking up is the bravest thing we can do.