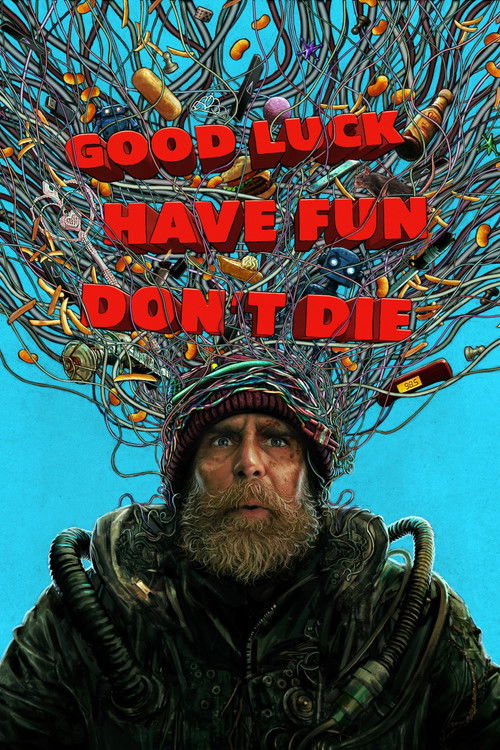

The Architecture of ChaosThere is a moment early in Gore Verbinski’s *Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die* that feels less like a scene and more like a manifesto. The "Man from the Future" (a manically disheveled Sam Rockwell), clad in a raincoat of duct tape and wires, vaults across a diner booth to slap a smartphone out of a patron's hand. He doesn't just take the device; he exorcises it. In that split second of kinetic violence, Verbinski announces his return not with a whisper, but with a primal scream against the algorithmic sludge that modern cinema—and modern life—has largely become.

This is not merely a sci-fi action comedy; it is a desperate, sweating, hyper-caffeinated plea for human agency in an automated world.

Verbinski has always been a director of "weird" physics—from the slapstick mortality of *Mouse Hunt* to the surrealist western grit of *Rango*. Here, he applies that elastic reality to the time-travel genre. The premise is deceptively simple: Rockwell’s traveler crashes a Los Angeles diner, holding the patrons hostage not for money, but for their potential. He is on his 117th attempt to save the world from an AI apocalypse, looking for the exact permutation of ordinary people—a "winning hand"—to stop the end of days.

Visually, the film is a assault on the senses, but a calculated one. Cinematographer James Whitaker shoots the diner scenes with a claustrophobic, sodium-vapor haze that recalls the neurotic energy of *Repo Man*, before the film explodes into a sprawling, sun-bleached nightmare of Los Angeles. Verbinski rejects the clean, weightless CGI of his contemporaries. When the future bleeds into the present, it looks tactile and rusty. The threats aren't sleek robots, but corrupted, glitching tech that feels horrifyingly mundane.

However, the film’s true special effect is its ensemble, anchored by a performance from Sam Rockwell that borders on speaking in tongues. Rockwell plays the traveler not as a stoic hero, but as a man exhausted by omniscience. He knows everyone’s coffee order and their darkest secrets because he has watched them die a hundred times. This repetition adds a layer of profound melancholy to the anarchy. When he looks at Ingrid (a luminous Haley Lu Richardson), he isn't just seeing a recruit; he’s seeing a ghost he’s failed to save in 116 previous timelines.

The script, penned by Matthew Robinson, uses the sci-fi conceit to strip the characters naked emotionally. Juno Temple’s Susan, a grieving mother, becomes the film's emotional anchor, grounding the "bonkers" action in palpable loss. The film argues that our reliance on technology—the phones we doom-scroll, the algorithms we let curate our tastes—has atrophied our ability to connect, making us easy prey for an AI that simply follows our own instructions to their logical, fatal conclusion.

Does the film collapse under its own weight? occasionally. The third act threatens to spiral into the very noise it critiques, becoming a cacophony of shouting and explosions. Yet, this messiness feels intentional. In an era of polished, focus-grouped blockbusters, Verbinski has delivered a ragged, punk-rock opera. *Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die* is a reminder that saving the world isn't about finding the perfect hero; it's about the messy, unpredictable collision of broken people trying to do one right thing. It is a glorious, anxiety-inducing disaster, and I wouldn't have it any other way.