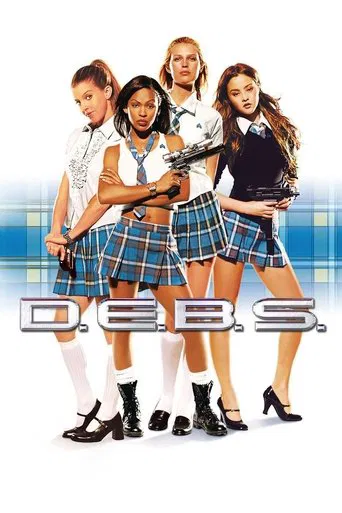

The Aesthetics of EmptinessIf *Drive-Away Dolls* was Ethan Coen and Tricia Cooke shaking off the dust of the Coen Brothers’ legacy with a road-trip giggle, *Honey Don’t!* is their attempt to linger in the smoke of a burnt-out cigarette. This second entry in their self-described "lesbian B-movie trilogy" trades the kinetic energy of the highway for the stagnant heat of Bakersfield, California. While it ostensibly wears the trench coat of a neo-noir, the film is less interested in solving a mystery than in striking a pose. It is a work of aggressive stylization, a candy-colored pulp comic that feels simultaneously over-caffeinated and narratively exhausted.

Visually, the film is a fascinating contradiction. Coen and cinematographer Ari Wegner capture the parched landscapes of the Central Valley with a sun-baked brutality that recalls *Blood Simple*, yet the interiors are pure camp theater. Honey O'Donahue (Margaret Qualley) operates out of a world that feels unstuck in time—she drives a muscle car and clings to payphones in a post-COVID world, a deliberate anachronism that underscores her detachment from reality. The film's aesthetic is a "noir cosplay," where the textures of leather, desert dust, and cheap motel sheets are rendered with fetishistic care. It creates a suffocating sense of reality where the heat waves distort not just the horizon, but morality itself.

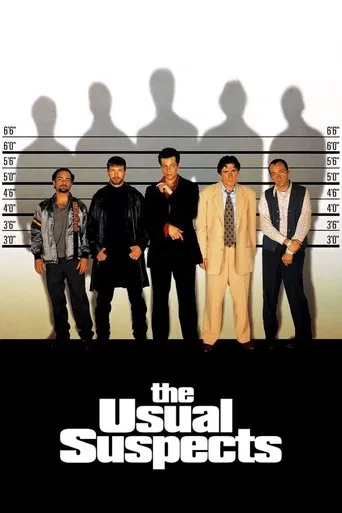

However, the narrative collapses under its own ambition to be "vibes-first" cinema. The central mystery—involving a dead client, a cult-like church, and a drug ring—is treated with such cavalier indifference that it becomes impossible for the audience to invest in the stakes. The screenplay, co-written by Coen and Cooke, seems allergic to genuine tension, preferring to undercut every moment of potential dread with a quip or a sexual detour. While the sex positivity is refreshing—the film is unapologetically horny, treating queer desire as a primary engine rather than subtext—it often feels like a distraction from a hollow core.

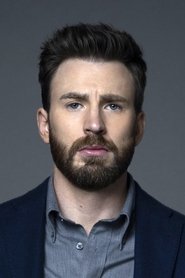

The film’s salvation lies entirely in its performances, specifically the friction between Qualley and her co-stars. Qualley plays Honey not as a hardened cynic, but as a woman performing the role of a detective, her brow permanently furrowed in a caricature of concentration. Her chemistry with Aubrey Plaza’s MG Falcone is electric, a dangerous dance of mutual suspicion and attraction that provides the film’s only real emotional gravity. Plaza, operating in her usual register of deadpan menace, anchors the film when it threatens to float away into pure absurdity. Conversely, Chris Evans, cast against type as the sleazy Reverend Drew Devlin, chews the scenery with a manic energy that suggests he is in a different movie entirely—a cartoon villain in a story that desperately needed a terrifying one.

Ultimately, *Honey Don’t!* is a film that demands to be looked at rather than watched. It is a collection of striking postcards from a trip that went nowhere. Ethan Coen seems to be wrestling with the ghost of his own filmography, attempting to replicate the nihilistic absurdity of *Burn After Reading* or *The Big Lebowski* without the structural discipline that made those films masterpieces. It leaves us with a lingering sense of style, a few memorable images of neon and dust, but a silence where the heart of the story should be.