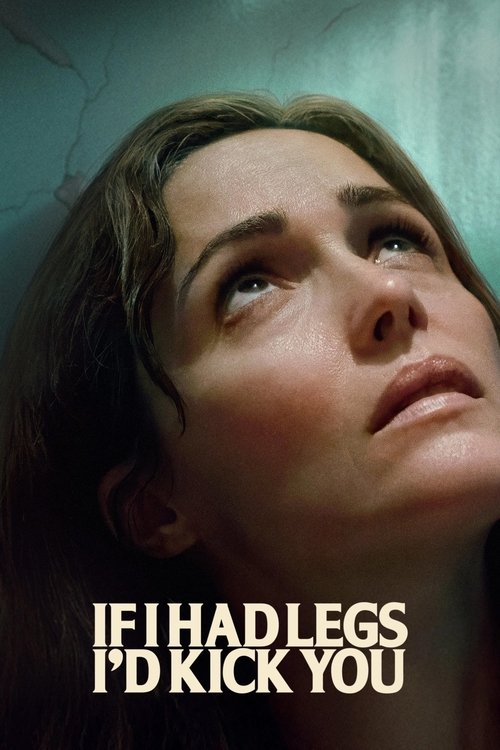

The Architecture of UnravelingIn the seventeen years since Mary Bronstein’s debut feature *Yeast*, the landscape of American independent cinema has shifted, but the specific frequency of anxiety she captures—a high-pitched, vibrating wire of feminine desperation—remains singularly her own. Her long-awaited return, *If I Had Legs I’d Kick You*, is not merely a portrait of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown; it is a structural dissection of the collapse itself. While comparisons to the frenetic cinema of the Safdie brothers (Josh Safdie produces here) are inevitable given the shared creative orbit, Bronstein operates in a different register. Where they often look outward at the chaos of the street, Bronstein looks inward, turning the domestic sphere into a pressure cooker where the lid has been welded shut.

The film introduces us to Linda (Rose Byrne), a therapist and mother whose existence has become a logistical nightmare of medical equipment and emotional deficit. Her daughter, suffering from a mysterious illness that requires tube feeding, is presented largely as a disembodied voice and a set of demands, a directorial choice that shrewdly forces the audience to inhabit Linda’s fraying perspective. We do not see the child as a subject of pity; we experience her as the architect of Linda's confinement. The visual language reinforces this claustrophobia. Bronstein and cinematographer Christopher Messina shoot Byrne in punishing close-ups, trapping her in the frame just as she is trapped in her life. The sound design is equally aggressive—the rhythmic, mechanical whir of the feeding pump becomes the film’s heartbeat, a relentless metronome counting down to an explosion that feels perpetually imminent.

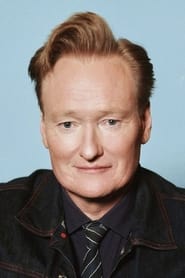

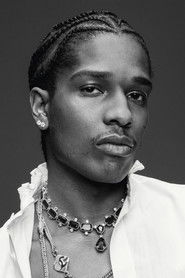

When the literal ceiling of her home collapses, flooding her life with brackish water and forcing a relocation to a motel, the film transitions from domestic drama to a kind of surrealist survival horror. This is where the screenplay shines, balancing the absurdity of the situation with the gravity of Linda’s internal state. The physical space of the motel becomes a purgatory where Linda interacts with a Greek chorus of oddities, including a motel superintendent played with surprising warmth by A$AP Rocky. Yet, the film’s most striking dialectic is found in the therapy scenes. Conan O’Brien, cast against type as Linda’s supervisor and therapist, delivers a performance of chilling restraint. He is a wall of professional silence against which Linda throws herself, his refusal to validate her spiraling logic serving as the ultimate provocation. It is a brilliant casting stroke; O’Brien’s familiar face promises levity, but he offers only a mirror to Linda’s disintegration.

At the center of this maelstrom is Rose Byrne, who delivers a performance that strips away all vanity. Linda is prickly, irrational, and frequently cruel—a "bad mother" by societal standards, but a profoundly human one by Bronstein’s. Byrne does not beg for the audience's sympathy; she demands our witness. She physicalizes the exhaustion of caregiving in a way that feels taboo, acknowledging the dark, intrusive thoughts that accompany the drudgery of keeping another human being alive. The film posits that the true horror of motherhood is not the sacrifice, but the isolation of the experience—the screaming into a void that refuses to echo back.

*If I Had Legs I’d Kick You* is an endurance test, certainly, but one that yields a terrifying clarity. It rejects the sanitized cinematic narrative of resilience in favor of something messier and more honest. Bronstein has crafted a film that feels less like a story and more like a panic attack captured on celluloid, asking us to sit in the discomfort until we, like Linda, learn to breathe underwater.