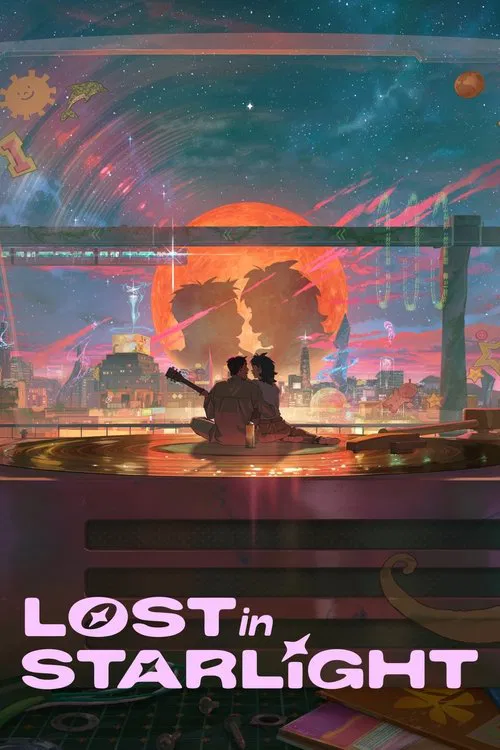

The Space Between UsIn the vast, silent vacuum of cinema, the "long-distance relationship" has long been a favored trope, usually measured in time zones or train rides. But in Han Ji-won’s *Lost in Starlight* (2025), the distance is measured in light-years, and the silence is absolute. Marking Netflix’s first foray into feature-length Korean animation, the film arrives not as a loud blockbuster clamoring for attention, but as a quiet, luminous meditation on the gravity of human connection. It is a work that asks a terrifying question: when we reach for the stars, do we inevitably let go of the hand holding ours on Earth?

Han, previously known for her delicate indie sensibilities in *The Summer*, scales up her vision without losing her intimacy. The film is set in a 2050 Seoul that eschews the dystopian grays of *Blade Runner* for a warm, "retro-futuristic" vibrancy. Here, analog vinyl records spin alongside holographic displays, suggesting a future that yearns for its past. This aesthetic is not merely decorative; it is the film’s central thesis. We are moving forward, Han suggests, but we are desperate to carry our memories with us.

Visually, *Lost in Starlight* is a triumph of atmosphere over action. The animation style evokes the hyper-realism of Makoto Shinkai—rain slicking the neon streets, light fracturing through glass—but tempers it with a distinct, softer character design that feels uniquely Korean. One specific sequence stands out as a masterclass in visual storytelling: a hallucinatory moment where the cosmos transforms into the grooves of a spinning vinyl record. It is a dizzying, beautiful conflation of the infinite and the intimate, visually arguing that a single song can hold as much weight as a galaxy. The sound design mirrors this, contrasting the deafening roar of rocket launches with the suffocating quiet of a bedroom where a text message remains unread.

At its core, the film rests on the shoulders of Nan-young (voiced with steely vulnerability by Kim Tae-ri) and Jay (Hong Kyung). Nan-young is not the typical wide-eyed dreamer; she is a scientist haunted by the ghost of her mother, an astronaut who never returned. Her desire to go to Mars is less about exploration and more about a cosmic form of closure. Jay, a musician paralyzed by his own artistic stagnation, becomes her tether to Earth. The "meet-cute" involving a broken turntable is perhaps the film’s only concession to genre cliché, but the relationship that follows is refreshingly adult. They do not merely pine; they negotiate the terms of a love that has an expiration date.

The film’s true bravery lies in its refusal to offer easy answers. As Nan-young departs for the Red Planet, the narrative fractures into a "Voices of a Distant Star" dynamic, where communication lag stretches from minutes to hours, then days. The horror of the film is not alien monsters or technical failure, but the silence between messages. Han captures the specific modern anxiety of the "delivered" status, magnified by millions of miles. Kim Tae-ri’s voice performance is exceptional here; she conveys a sense of professional detachment that slowly cracks to reveal a terrified daughter and lover beneath the spacesuit.

If *Lost in Starlight* stumbles, it is perhaps in its third act, which leans heavily into metaphysical abstraction that may alienate viewers looking for a concrete resolution. Yet, this ambiguity feels earned. The film posits that love, like space travel, is an act of faith—a belief that something exists in the void even when you cannot see it.

Ultimately, *Lost in Starlight* is a significant milestone for Korean animation, proving it can compete with the emotional depth and technical prowess of its Japanese neighbors while carving out its own identity. It is a film that reminds us that while our feet may leave the ground, our hearts remain stubbornly subject to Earth's gravity. It is a beautiful, aching journey that suggests the farthest distance is not between planets, but between two people who can no longer touch.