The Refiner’s FireIf cinema is a mirror, the films of Alex Kendrick are less a reflection of the world as it is, and more a blueprint of how a specific segment of it wishes it to be. With *The Forge* (2024), Kendrick returns to the universe of his 2015 hit *War Room*, but shifts the lens from the domestic battlefield of marriage to the internal forge of young manhood. While it carries the unmistakable DNA of a sermon, to dismiss it merely as a "message movie" is to overlook its fascinating, if occasionally didactic, engagement with the crisis of modern masculinity. This is not subtle filmmaking, but it is possessed of a clarity of purpose that is rare in an era of narrative ambiguity.

Visually, *The Forge* operates with a utilitarian competence that marks a step up for the Kendrick Brothers. The director utilizes the industrial aesthetic of the film's setting—a manufacturing plant—to ground his theological metaphors. The sparks of welding torches and the grinding of metal are not just background noise; they are the visual lexicon for the protagonist's soul. Kendrick often frames his characters in two distinct modes: the chaotic, cluttered interiors of Isaiah’s aimless adolescence (screens, headphones, darkened bedrooms) and the structured, illuminated spaces of his mentorship. The camera does not judge Isaiah so much as it observes his inertia, allowing the audience to feel the suffocating weight of his potential energy waiting for a spark.

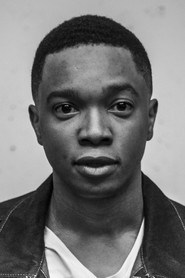

At the narrative's center is Isaiah Wright (Aspen Kennedy), a nineteen-year-old drifting in the purgatory between high school and "real life," anesthetized by video games and resentment. The film’s emotional intelligence shines in its depiction of the single-mother dynamic. Priscilla Shirer, reprising her role as Cynthia (sister to her character in *War Room*), delivers a performance of exhausted love that anchors the film. Her ultimatum to Isaiah—"step up or move out"—isn't played for melodrama, but as a terrified act of necessary severity. Kennedy, conversely, effectively captures the defensive sullenness of a young man who knows he is failing but lacks the tools to stop.

The film’s "heart," however, beats in the mentorship between Isaiah and Joshua Moore (Cameron Arnett), a successful businessman who runs his company like a discipleship incubator. Their interactions form the spine of the film. In one widely discussed sequence, Moore utilizes a literal sword-forging analogy to break down Isaiah’s ego. To a secular eye, the dialogue here can feel heavy-handed—characters essentially speak in parables. Yet, within the context of the genre, it works because Arnett plays Moore not as a saint, but as a man who has already walked through the fire. The chemistry between mentor and mentee allows the film to explore the ache of fatherlessness without devolving into pity; it offers structure as the antidote to abandonment.

Ultimately, *The Forge* is a film about the friction required for change. It argues that character is not innate, but manufactured through intentional stress and heat. While it suffers from the pacing issues common to its genre—scenes often run long to ensure the moral is fully articulated—it succeeds in its specific ambition. It does not try to be a broad cultural blockbuster; it aims to be a functional tool for its community. In a cinematic landscape often obsessed with deconstructing heroes, Kendrick offers a sincere, if prescriptive, manual on how to build one.