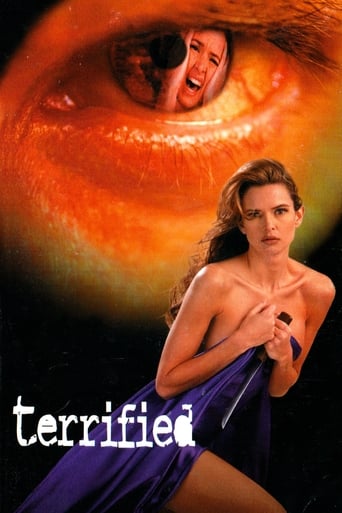

✦ AI-generated review

The Frozen Dial

Sequels in the horror genre typically operate on a principle of escalation: more blood, higher body counts, louder screams. They are rarely exercises in restraint, and even more rarely do they attempt to mature alongside their audience. *The Black Phone 2*, however, is not interested in merely repeating the jump scares of 2021. By shifting the setting from the suffocating claustrophobia of a suburban basement to the vast, agoraphobic whiteout of a Colorado blizzard, director Scott Derrickson has crafted a film that is less about the return of a monster and more about the freezing effect of trauma.

Set four years after the original, in 1982, the film finds siblings Finney (Mason Thames) and Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) navigating the treacherous waters of high school. If the first film was a Spielbergian nightmare of middle school vulnerability, this sequel is a meditation on the PTSD of survival. Derrickson and co-writer C. Robert Cargill made the astute decision to wait for their young actors to age naturally, allowing the narrative to evolve from a "boy in a well" story into a complex study of two teenagers who survived the unspeakable but are still trapped in its orbit.

Visually, the film is a striking departure. The warm, grainy textures of the 1970s have been replaced by the stark, clinical cold of the early 80s. The shift to the "Alpine Lake" winter camp provides a new visual language; where the first film used walls to confine, this one uses weather. The blizzard that traps the protagonists serves as a potent metaphor for Dante’s Ninth Circle of Hell—a treachery defined not by fire, but by ice. Derrickson’s camera captures the snow not as a wonderland, but as a blank page that refuses to let the past remain buried.

The heart of the film remains the unbreakable bond between Finney and Gwen. McGraw, in particular, is a revelation. Her Gwen is no longer just a spunky comic relief with a divine gift; she is a young woman burdened by visions that feel less like superpowers and more like a curse. The scene where she first dreams of the winter camp—a sequence shot with a disorienting, tilt-shift lens effect—establishes the film’s dream logic. It is here that the Black Phone rings again, not as a physical object, but as a psychic intrusion.

The return of Ethan Hawke as The Grabber was the production's biggest risk. How do you bring back a dead villain without cheapening his demise? Derrickson solves this by positioning The Grabber not as a resurrected slasher, but as a haunting. Hawke plays the role with a terrifying, spectral glee, embodying the idea that violence echoes long after the weapon is dropped. His presence is felt more in the atmosphere than in physical confrontation, making him a symbol of the "ghosts" that abuse survivors carry with them.

A particularly inspired choice is the casting of Miguel Mora as Ernesto, the brother of the first film’s victim, Robin. Seeing the face of a dead friend on a living boy adds a layer of melancholic surrealism to Finney’s journey, constantly reminding him—and the audience—of what was lost.

*The Black Phone 2* avoids the trap of being a "franchise product." It doesn’t set up a universe so much as it deepens a wound. It argues that escaping the basement was only the beginning; the real horror is learning how to live in a world that remembers you as a victim. Tense, emotionally resonant, and visually chilling, it is a rare sequel that earns its dread.