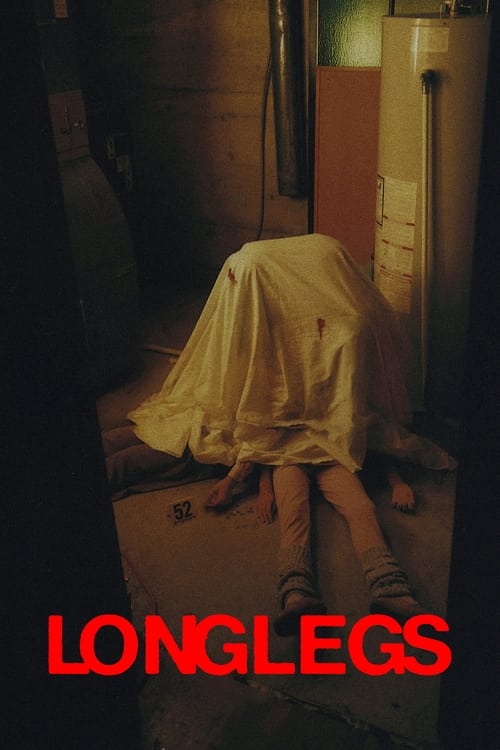

✦ AI-generated review

The Anatomy of a Nightmare

It is perhaps inevitable that Osgood Perkins, the son of *Psycho* star Anthony Perkins, would eventually craft a film that feels less like a narrative and more like a hereditary curse. In *Longlegs*, Perkins does not merely direct a horror movie; he conducts a séance for the specific, grainy dread of the 1990s. While the film wears the skin of a police procedural—inviting immediate and somewhat superficial comparisons to *The Silence of the Lambs*—it has no interest in the comfort of logic. Where Clarice Starling solves a puzzle, Agent Lee Harker is asked to remember a nightmare. The result is a film that operates on dream logic, a suffocating masterpiece of atmosphere where the true horror is not the killer you catch, but the family secrets that catch you.

From its opening moments, *Longlegs* establishes a visual language of isolation. Shot in a claustrophobic 4:3 aspect ratio, the prologue introduces us to a snowy Oregon landscape and a young girl who meets a stranger in a station wagon. The scene is quiet, almost banal, until the stranger’s voice—a high-pitched, nursery-rhyme croon—shatters the peace. Perkins utilizes negative space with weaponized precision throughout the film; characters are frequently framed in the lower third of the screen, crushed by the weight of the empty space above them. It creates a subliminal anxiety, forcing the viewer to scan the background for threats that may or may not be there. The camera does not just observe; it stalks.

At the center of this wide-angle desolation is Maika Monroe as FBI Agent Lee Harker. Monroe gives a performance of restrained interiority, playing Harker not as a stoic action hero but as a woman vibrating with repressed trauma. She is "half-psychic," a trait the film treats less like a superpower and more like a wound that hasn't healed. Her stillness is a defense mechanism. Against her silence, Nicolas Cage’s titular killer is a glamorous, grotesque explosion. Cage, channeled through layers of prosthetics and the spirit of a decaying glam-rock star, delivers a performance that is undeniably "gonzo," yet perfectly calibrated to the film’s frequency. He is the boogeyman of the Satanic Panic era made flesh—loud, absurd, and terrifying because he seems to operate by laws of physics that do not apply to the rest of us.

However, to view *Longlegs* simply as a cat-and-mouse thriller is to miss its tragic heart. Beneath the occult ciphers and the T. Rex lyrics lies a devastating commentary on maternal love and the corrosive nature of protection. The revelation of the complicity involved—the lengths a parent will go to ensure their child is "allowed to grow up"—twists the knife. The horror is not just that the Devil exists, but that he was invited into the living room to keep the peace. The film suggests that the nuclear family is not a sanctuary, but a containment unit for evil.

The film’s conclusion offers no cathartic release, no neat tying of bows. In the final scenes, as the gun clicks empty and the doll remains whole, Perkins denies us the victory of the "good guy with a gun." We are left with the sinking realization that trauma is not something you defeat; it is something you inherit. *Longlegs* is a rare achievement in modern horror: a film that doesn't just want to scare you for ninety minutes, but wants to stain your memory, lingering like the hum of a disconnected telephone line.