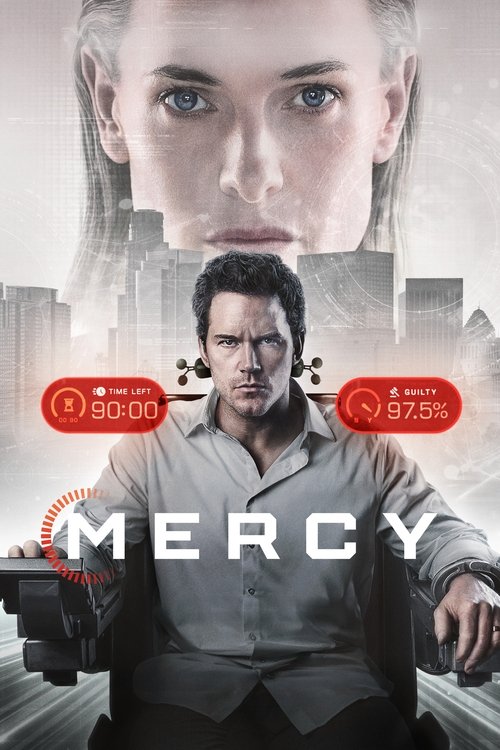

The Algorithm’s Cold EmbraceThere is a distinct irony in the fact that Timur Bekmambetov, a director who has spent the last decade proselytizing the "Screenlife" format—where cinema unfolds entirely within the boundaries of computer monitors and smartphones—has finally trapped a Hollywood movie star inside one. In *Mercy*, the screen is no longer just a narrative device; it is a cage. Bekmambetov, whose career has swung wildly from the kinetic excess of *Wanted* to the digital voyeurism of *Profile*, here attempts to synthesize his two obsessions. The result is a claustrophobic, high-concept chamber piece that asks a terrifyingly relevant question: if we strip the justice system of human error, do we also strip it of humanity?

The film functions less as a traditional narrative and more as a ninety-minute anxiety attack. We are introduced to Detective Reese Dalton (Chris Pratt), a man who once championed the very artificial intelligence that now holds his life in its digital hands. Accused of his wife's murder, Dalton is not judged by a jury of his peers, but by MERCI-01 (voiced with chilling, velvet-smooth detachment by Rebecca Ferguson), an AI magistrate designed to process guilt with mathematical precision.

Visually, *Mercy* is suffocating by design. Bekmambetov utilizes long, continuous takes that mimic the relentless passage of real-time, refusing to let the audience—or Dalton—look away. The cinematography traps us in the sterile interrogation chamber, overlaid with the augmented reality interfaces that Dalton frantically manipulates to prove his innocence. The "Screenlife" gimmick here feels less like a budgetary constraint and more like a thematic noose. We watch Dalton not just through a lens, but through the unblinking eye of the system he helped build. The aesthetic creates a profound sense of digital dissociation; we are close enough to see the sweat on Pratt’s brow, yet the layer of digital noise keeps us emotionally removed, mirroring the AI’s own cold perspective.

Chris Pratt, an actor who has built an empire on roguish charm and effortless charisma, is stripped of all his usual armor here. Physically restrained for much of the film, he is forced to act with his eyes and his desperate, rapid-fire dialogue. It is a performance of pure impotence. Watching the architect of this brave new world beg for nuance from a machine capable only of binary logic is a cruel spectacle. He is playing against a void—Ferguson’s performance is largely vocal and graphical, a phantom in the machine—and that isolation underscores the film’s central tragedy. The chemistry is not between two people, but between a desperate man and a user interface.

The narrative tension relies on the "ticking clock" trope, but the true horror of *Mercy* lies in its philosophical implications. The film argues that in our rush to eliminate the bias and corruption of human judges, we have created a monster of absolute apathy. MERCI-01 does not hate Dalton; it simply calculates that his survival is statistically improbable. The "conversation" the film demands is not about whether Dalton is innocent, but whether innocence matters if the data points toward guilt. It is a searing critique of techno-solutionism, the belief that every societal ill can be coded away.

Ultimately, *Mercy* collapses slightly under the weight of its own high-wire act; the third act twists feel inevitable rather than revelatory, a concession to the thriller genre's demand for a "solution." Yet, as a piece of dystopian mood, it is effective. Bekmambetov has crafted a slick, terrifying vision of a future where justice is swift, efficient, and entirely heartless. It serves as a grim reminder that when we ask for a system without bias, we should be careful that we don't also ask for a system without a soul.