✦ AI-generated review

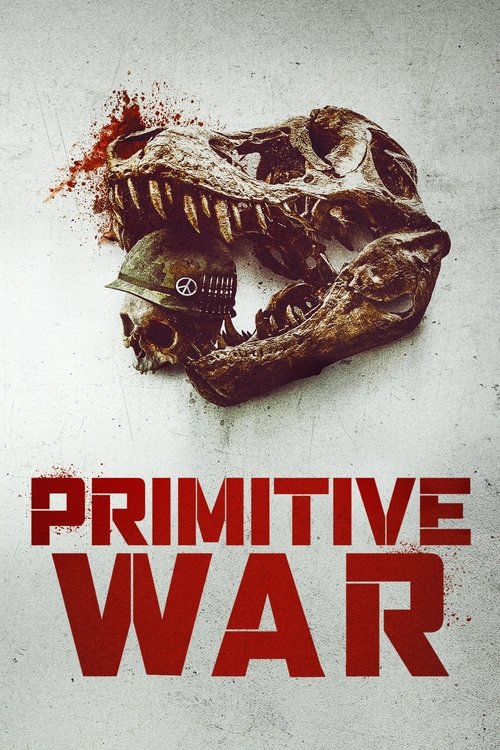

The Valley of Ancient Ghosts

The Vietnam War film is a genre so calcified in its own tropes—the whirling Huey blades, the needle-drop of Creedence Clearwater Revival, the weary cynicism of the grunt—that it has become a kind of modern mythology. Typically, these films suggest that the true monster is war itself, or perhaps the darkness inherent in the human soul. Luke Sparke’s *Primitive War* (2025) takes this metaphor and literalizes it with a boldness that borders on the delirious. By dropping a reconnaissance unit into a jungle infested not just with the Viet Cong but with resurrected dinosaurs, Sparke bypasses the subtle psychological horrors of *Apocalypse Now* for something far more primal. It is a film that asks a simple, audacious question: what if the "green hell" of the jungle was actually a gateway to a hell far older?

Sparke, an Australian filmmaker known for his ambitious, maximalist approach to independent sci-fi (*Occupation: Rainfall*), attacks this adaptation of Ethan Pettus’s novel with a commendable lack of restraint. Visually, the film operates in a fascinating state of friction. The cinematography by Wade Muller leans heavily into the gritty, desaturated palette of late-60s war cinema—grainy greens, sweaty close-ups, and the claustrophobic density of foliage. Yet, this "grounded" aesthetic collides headlong with the fantastical brightness of its creatures. Unlike the shadowed, rain-slicked tension of *Jurassic Park*, Sparke often stages his horrors in unforgiving daylight. It is a risky choice that sometimes exposes the seams of the film’s digital reach, but it also creates a unique, sun-baked anxiety. When a Utahraptor tears through a formation of soldiers, the terror isn’t hidden in the dark; it is exposed, bloody and bizarrely matter-of-fact.

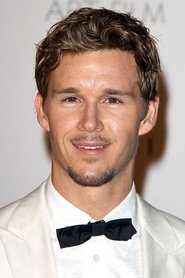

At the narrative center is Vulture Squad, a "dirty dozen" archetype led by Ryan Kwanten’s stoic Sergeant Baker. The script struggles initially to elevate these men beyond their military caricatures—we have the rookie, the cynic, the hardened vet. However, the film finds its rhythm when it shifts from a war drama to a survival siege. The sheer absurdity of the premise strips away the political baggage of the Vietnam setting, leaving only the raw mechanic of survival. There is a specific, widely discussed sequence involving a river crossing where the silence is weaponized; the water, usually a source of ambush by human enemies, becomes the domain of a massive aquatic predator. Here, the film achieves a genuine sense of dread, reminding us that in the face of an apex predator, ideology and nationality are irrelevant. We are all just meat.

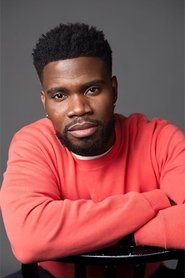

The film’s third act introduces a "Collider" sub-plot involving Cold War scientific overreach, a narrative pivot that threatens to topple the film into pure camp. Yet, the cast, particularly a scene-chewing Jeremy Piven and a grounded Tricia Helfer, play it with a straight face that anchors the madness. They treat the sudden appearance of a T-Rex not as a B-movie punchline, but as a tactical nightmare to be solved with rifles and grenades.

*Primitive War* is not a film of subtle introspection, nor does it possess the philosophical weight of the war films it mimics. But it succeeds as a piece of muscular, gonzo cinema because it refuses to wink at the audience. It treats its preposterous collision of eras with deadly seriousness. In doing so, Sparke has crafted a creature feature that feels distinct in a landscape of sanitized blockbusters—a jagged, bloody reminder that nature, whether ancient or modern, always holds the high ground.