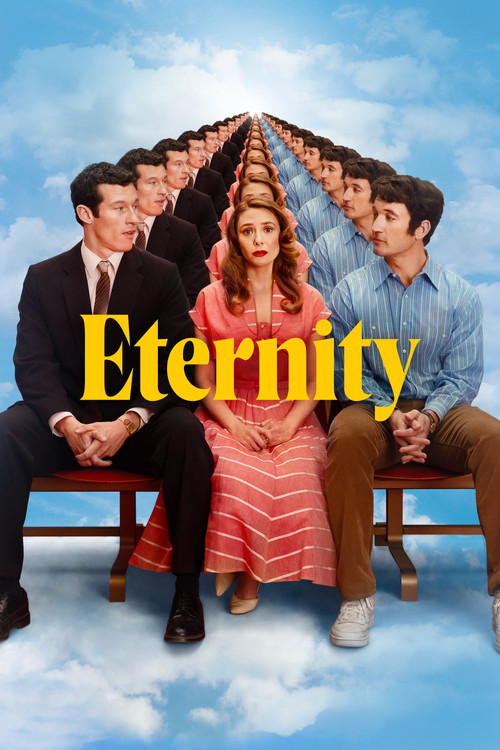

✦ AI-generated review

The Bureaucracy of Bliss

Cinema has spent a century obsessing over the afterlife, oscillating between the fire-and-brimstone morality plays of the 1940s and the metaphysical abstraction of recent art-house fare. But in *Eternity*, director David Freyne offers a third, distinctively modern option: the afterlife as a mid-century convention center, staffed by overworked bureaucrats and painted in the soothing, sterile pastels of a retirement community brochure. It is a vision of the great beyond that feels less like judgment day and more like a never-ending Sunday afternoon—comfortable, safe, and quietly terrifying.

Freyne, whose previous work demonstrated a sharp eye for the awkwardness of human connection, here graduates to a canvas of metaphysical ambition. *Eternity* posits that upon death, we are not weighed against a feather, but rather given a week to choose our permanent residence from a catalog of themed paradises. Into this candy-colored purgatory comes Joan (Elizabeth Olsen), a woman whose soul is suddenly the battleground for a conflict as old as the genre itself: the war between the Comfortable Real and the Idealized Hypothetical.

Visually, the film is a triumph of production design over terrifying existential implications. The "Junction"—the transit hub where souls decide their fate—is rendered with a Wes Anderson-esque fastidiousness. It is a world of soft curves, retro-futuristic terminals, and endless waiting rooms. This aesthetic choice is not merely decorative; it serves the narrative’s central thesis that eternity is, essentially, a curated vacation. By grounding the supernatural in the banality of travel logistics, Freyne creates a space where the characters’ emotional baggage feels heavier than the metaphysical stakes. We are lulled by the beauty of the set design, much like the characters are lulled into complacency, until the suffocating reality of the premise sets in: you have to choose, and you can never change your mind.

The film’s heart beats in the chest of Elizabeth Olsen, who performs a delicate high-wire act. As Joan, she is caught between Larry (Miles Teller), the husband of 65 years with whom she shared a life of authentic, messy domesticity, and Luke (Callum Turner), the first love who died young and has waited in this lobby for decades, preserved in the amber of youthful potential. This is not a choice between a hero and a villain; it is a choice between memory and imagination. Teller, shedding his usual bravado for a kind of prickly vulnerability, embodies the friction of long-term love—the bickering, the silence, the shared history that is as heavy as it is comforting. Turner, conversely, is the ghost of "what if," the romantic spark that never had the chance to fade into routine.

Where the film risks stumbling is in its reluctance to truly twist the knife. The script, at times, retreats into the safety of sitcom rhythms just as the emotional waters begin to deepen. The "Afterlife Coordinators" (played with scene-stealing dryness by Da'Vine Joy Randolph and John Early) provide ample levity, but occasionally undercut the profound sadness inherent in Joan's dilemma. There is a version of this movie that is a tragedy about the impossibility of satisfaction, but Freyne steers us gently back toward the warmth of the rom-com.

Ultimately, *Eternity* succeeds because it respects the dignity of its characters' confusion. It suggests that the tragedy of human life isn't that it ends, but that it forces us to exclude infinite other lives we could have lived. In asking Joan to choose one timeline forever, the film illuminates the beauty of the mortal world, where we are defined not by the eternity we select, but by the messy, linear, and finite choices we make every day. It is a sweet, beautifully dressed film that leaves a lingering, bittersweet aftertaste—a reminder that "forever" is a long time to be right, and an even longer time to be wrong.