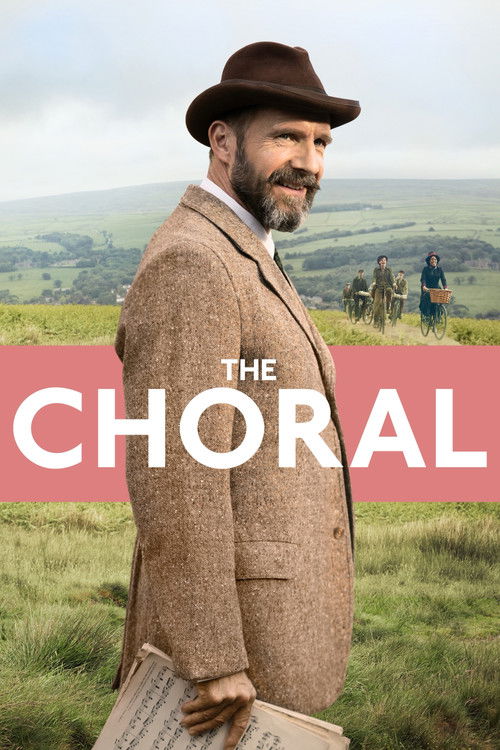

The Architecture of a SighThere is a specific, melancholy frequency that writer Alan Bennett and director Nicholas Hytner have tuned into for decades—a frequency where the grand tragedies of history vibrate against the teacups of provincial English life. In *The Choral*, their fourth and perhaps most tender collaboration, they return to this familiar territory, but the stakes have shifted. We are not in the chaotic classrooms of *The History Boys* or the eccentricity of *The Lady in the Van*. We are in Ramsden, Yorkshire, in 1916, where the silence left by the men gone to the Front is so deafening it can only be filled by the swell of a chorus.

To view *The Choral* merely as a "period drama" is to miss its sharper edges. It is, at its heart, a film about the architecture of grief. The narrative setup is deceptively quaint: the local choral society, decimated by the draft, must recruit teenagers and old men to bolster their ranks for a performance of Elgar’s *The Dream of Gerontius*. But Hytner, working with cinematographer Mike Eley, shoots the Yorkshire Dales not as a pastoral idyll, but as a landscape holding its breath. The opening sequence, where figures emerge from the mist like ghosts of the future dead, establishes a visual language of disappearance. The war is rarely seen, yet it is the phantom limb twitching in every frame.

Into this vacuum steps Dr. Henry Guthrie, played with a prickly, exacting brilliance by Ralph Fiennes. Guthrie is a Bennett archetype—the intellectual outsider—but Fiennes imbues him with a terrifying fragility. An atheist, a homosexual, and a Germanophile in a town gripped by jingoistic fervor, Guthrie is a walking provocation. The film’s central conflict is not the war itself, but the battle for the town’s soul. The community wants to sing to forget; Guthrie demands they sing to understand. His insistence on performing Elgar—a Catholic work about the journey of a soul through death—is an act of artistic defiance. He forces a community terrified of the telegram boy to look purgatory in the eye and harmonize with it.

The brilliance of the script lies in how it handles the "loss of innocence." The young recruits (played with raw energy by newcomers like Oliver Briscombe and Taylor Uttley) treat the choir not as a solemn duty, but as a hormonally charged social club—a place to flirt before the inevitable conscription papers arrive. Hytner captures these rehearsals with a kinetic fluidity, the camera sweeping through the ranks, contrasting the weathered faces of the old men (the superb Mark Addy and Alun Armstrong) with the fresh, doomed faces of the boys. It is a visual polyphony of generations: those who have survived, and those who are waiting to be spent.

Critics often accuse Bennett of being too "stagey," but here, the theatricality is the point. These characters are performing normalcy while their world collapses. When the choir finally achieves a moment of unity, the sound is not triumphant in the Hollywood sense; it is a desperate, beautiful assertion of existence. The music does not save them from the war—art, the film argues, is not a shield. It is simply the only way to endure the unendurable.

*The Choral* is a film of quiet devastation. It suggests that in the face of mechanized slaughter, the most radical act a civilization can perform is to gather in a drafty hall and insist on the precise execution of a crescendo. It is a minor-key masterpiece, leaving us not with a bang, but with the lingering resonance of a collective sigh.