✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Resentment

There is a distinct tragedy in watching a beautiful thing be dismantled by the very hands that built it. Jay Roach’s *The Roses* (2025) understands this paradox intimately, presenting marriage not as a sanctuary, but as a meticulously designed structure that—like the ill-fated museum Theo designs in the film’s first act—is vulnerable to the slightest shift in the atmospheric pressure of ego. While inevitable comparisons will be drawn to Danny DeVito’s 1989 adaptation of the Warren Adler novel, Roach’s film is less a remake and more a renovation, stripping the story down to its studs to examine how modern ambition rots the foundations of domesticity.

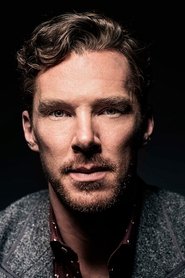

Roach, a director often associated with broad political docudramas and slapstick, here adopts a visual language that is deceptively glossy. The cinematography by Florian Hoffmeister bathes the Roses’ life in the warm, inviting hues of a high-end real estate listing. This is crucial to the film’s satirical bite: the battlefield is not a gothic dungeon, but a sun-drenched, open-concept kitchen. The "smart home" that Theo (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Ivy (Olivia Colman) inhabit becomes a third character—a technological panopticon that records their dissolution. When the violence erupts, it feels all the more violating because it shatters such a curated aesthetic. The destruction of Ivy’s prized Julia Child oven is not just a property dispute; it is an act of desecration against her identity.

At the center of this debris field are Cumberbatch and Colman, two actors who elevate the material from screwball farce to a study in psychological fragility. Cumberbatch plays Theo not as a monster, but as a man suffering from a distinctly modern form of emasculation. When his architectural career literally collapses, he doesn't just lose a job; he loses the "great man" narrative he had written for himself. Watching him shrink into the role of a resentful stay-at-home husband while Ivy’s culinary star rises is painful precisely because he plays it with such wounded, pathetic dignity.

Colman, meanwhile, is a revelation of suppressed fury. Her Ivy is not the shrill harpy of misogynistic divorce comedies, but a woman waking up to the realization that her support was the scaffolding holding up her husband’s fragile genius. The film’s most potent scene is arguably their "meet-cute" flashback, where Theo asks to borrow a knife in a restaurant kitchen—ostensibly for a suicide attempt, but played as a flirtation. It is a moment of electric chemistry that Roach wisely uses to twist the knife later; we mourn their hatred because we so fully believed in their love.

The script, penned by Tony McNamara (*The Favourite*), injects the dialogue with a lethal, rhythmic precision that creates a dissonance with Roach's sometimes too-gentle direction. McNamara’s words are razor blades wrapped in silk, exposing the transactional nature of their union. However, the film occasionally hesitates to fully embrace the abyss. Where the 1989 film was a nihilistic descent into hell, *The Roses* flirts with the idea of redemption, offering a glimmer of hope that feels somewhat unearned given the scorched earth that precedes it.

Ultimately, *The Roses* is a sharp, if occasionally uneven, critique of the "power couple" mythos. It suggests that in a world where success is a zero-sum game, a marriage of equals is impossible if both partners demand to be the protagonist. Roach has crafted a film that asks us to laugh at the absurdity of two people destroying their lives over material possessions, all while quietly reminding us that the things we own often end up owning us.