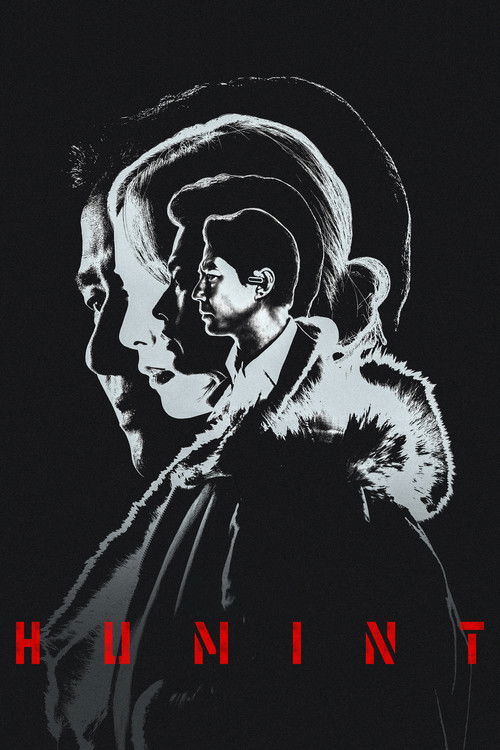

The Silent War of the HeartIn the lexicon of espionage cinema, "HUMINT"—human intelligence—usually implies a transactional relationship: information extracted from flesh and blood, often at the cost of the latter. But in Ryoo Seung-wan’s latest directorial effort, the term becomes a desperate plea. After the suffocating heat of *Escape from Mogadishu* and the maritime brawls of *Smugglers*, Ryoo has turned his gaze to the freezing greys of Vladivostok. Here, in a city that feels like the end of the world, he constructs a film that is less about statecraft and more about the crushing weight of intimacy in a profession designed to destroy it. *HUMINT* is not merely an action film; it is a tragedy of proximity, asking how we can touch another human being when every hand is trained to hold a weapon.

Ryoo’s visual language has matured into a terrifying precision. Collaborating again with cinematographer Choi Young-hwan, he captures Vladivostok (doubled by the stark architecture of Latvia) not as a playground for stunts, but as a purgatory of concrete and ice. The camera moves with a predator’s patience, stalking the characters through steam-filled dumpling shops and wind-battered ports. Unlike the kinetic frenzy of *Veteran*, the action here is punctuated by breathless silences. The violence, when it erupts, is ugly and desperate—less a choreographed dance and more a series of frantic collisions. A standout sequence involving a triangular standoff in a cramped apartment doesn’t rely on bullet time, but on the terrifying intimacy of three men realizing that pulling the trigger means ending their own souls, not just a mission.

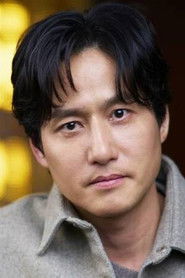

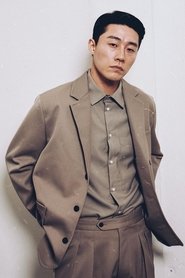

At the center of this frozen vortex is a quartet of performances that elevate the material beyond genre tropes. Zo In-sung, returning as the South Korean NIS agent Chief Jo, strips away his usual charismatic veneer to play a man hollowed out by duty. He is the film’s anchor, a professional who knows the game is rigged but plays it anyway. However, the film’s emotional reactor is Park Jeong-min as the North Korean security officer Park Geon. With a performance of coiled intensity, he portrays a man whose ideological armor is shattered not by a bullet, but by the quiet devastation of love. His scenes with Shin Sae-kyeong—who delivers a career-best performance as the reluctant informant Seon-hwa—are masterclasses in restraint. They convey a romance that exists entirely in the subtext, a longing so palpable it makes the surrounding gunfire feel secondary.

The film’s central conflict is not the search for a "mole" or a MacGuffin, but the struggle to remain human in a system that demands you become data. Ryoo deftly critiques the machinery of the divided peninsula, showing us that the "enemy" is rarely the man across the border, but the callous bureaucracies that view these agents as disposable assets. The character of the North Korean Consul (played with chilling menace by Park Hae-joon) represents this dehumanization—a man who sees people only as leverage. The tragedy of *HUMINT* is that for Geon and Seon-hwa to survive, they must become "intelligence" rather than individuals, a sacrifice the film mourns in every frame.

Ultimately, *HUMINT* cements Ryoo Seung-wan’s status as a director who refuses to let the blockbuster scale dilute the human stain. It lacks the triumphant escapism of his earlier hits, replacing it with a melancholic bruise that lingers long after the credits roll. By the time the snow settles on the blood-stained streets of Vladivostok, we are left with a haunting realization: in the shadow wars of the 21st century, the most dangerous thing a spy can possess is not a state secret, but a beating heart. This is cinema that chills the bone to warm the spirit, a grim yet beautiful reminder that even in the coldest places, humanity struggles to breathe.