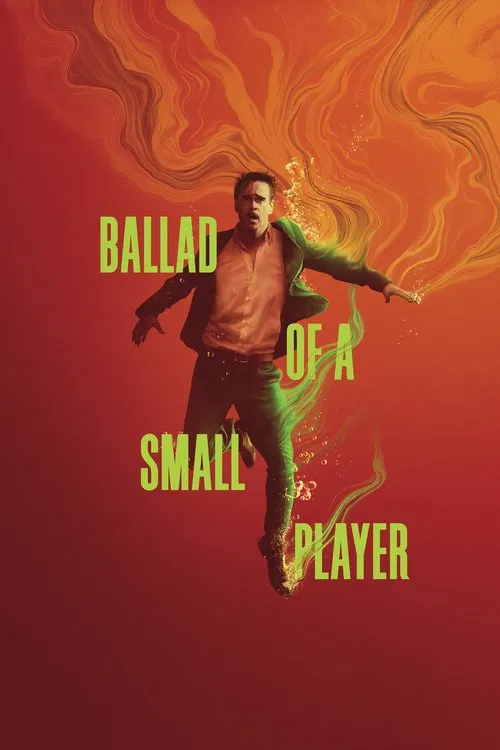

The Hungry Ghost of MacauIn the neon-choked arteries of Macau, where day is indistinguishable from night and luck is a deity more demanding than any god, Edward Berger finds his latest playground. Following the muddy trenches of *All Quiet on the Western Front* and the hermetic whispers of *Conclave*, Berger’s *Ballad of a Small Player* (2025) feels like a fever break—a delirious, sweat-slicked plunge into the purgatory of addiction. Adapted from Lawrence Osborne’s novel, the film is less a crime thriller than a spiritual autopsy of a man who has decided that losing is the only way to feel alive. It is a film that vibrates with the anxiety of a hand waiting to be turned over, asking us not if the protagonist will win, but if he even wants to.

Berger’s visual language here is a radical departure from the austere discipline of his previous work. He and cinematographer James Friend treat Macau not as a city, but as a hallucination. The frame is often suffocated by gold and crimson, the camera prowling the baccarat tables with a predatory restlessness. There is a "pop-up book" quality to the interiors—lavish, artificial, and suffocating—that mirrors the fraudulent existence of "Lord Doyle" (Colin Farrell). Berger uses reflections constantly; Doyle is rarely seen directly, but rather refracted through glass, polished marble, and the glossy eyes of fellow gamblers. This is a visual thesis on identity: Doyle is a copy of a copy, a man playing a role so deeply that the original self has long since dissolved into the humidity.

At the center of this kaleidoscope is Colin Farrell, delivering a performance of physical and emotional exhaustion that anchors the film’s flightier metaphysical ambitions. As Doyle, a disgraced financier masquerading as an aristocrat, Farrell is a study in manic desperation. He doesn't just play the addiction; he embodies the superstitious terror of it. Watch his hands during the baccarat scenes—the way he squeezes the cards, "peeking" at the pips as if trying to physically alter reality through sheer will. It is a grotesque ballet of hope and fatalism. His relationship with the enigmatic Dao Ming (Fala Chen) offers a grounding tether, but the film’s true antagonist is the supernatural weight of the "Hungry Ghost Festival." Berger suggests that Doyle is already a ghost, haunting the casinos because he has nowhere else to go. Tilda Swinton, as the eccentric investigator pursuing him, serves as a bizarre, almost Brechtian reminder of the reality Doyle is fleeing, though her tonal eccentricity sometimes threatens to capsize the film's mood.

Ultimately, *Ballad of a Small Player* is a polarizing entry in Berger’s filmography because it refuses to offer the catharsis of a traditional redemption arc. It posits that for the true gambler, the money is irrelevant; the point is the suspension of time, the moment between the bet and the reveal where anything is possible. The narrative occasionally buckles under its own philosophical weight, and the supernatural elements can feel opaque to the uninitiated. Yet, as a sensory experience, it is undeniable. Berger has crafted a film that feels like a long night in a casino: disorienting, seductive, and tinged with the creeping dread that eventually, the house always takes it all.