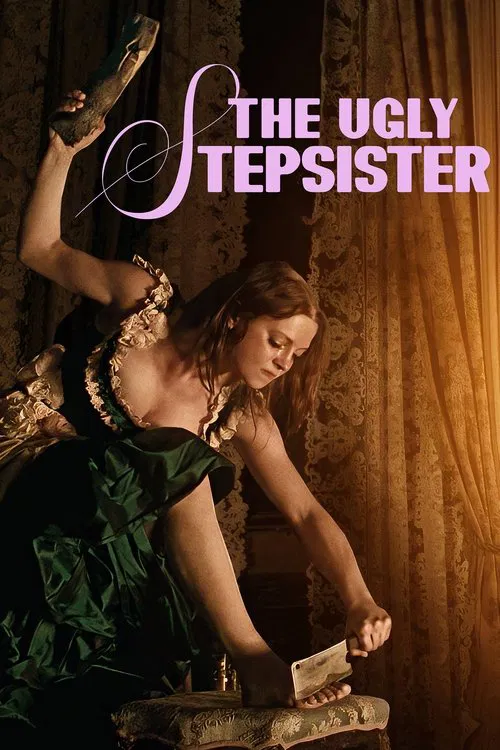

The Guillotine of GlamourIf the fairy tale is a machine for teaching children morality, Emilie Blichfeldt’s *The Ugly Stepsister* is the wrench thrown into its gears. We have grown accustomed to the revisionist fable—the villain’s origin story, the misunderstood witch—but Blichfeldt’s feature debut offers something far more visceral than a simple perspective shift. This is not merely a story about the "other" sister; it is a blood-soaked, candy-colored indictment of the industrial complex of beauty. By dragging the subtext of Perrault and Grimm into the harsh light of body horror, Blichfeldt transforms the pursuit of a "happily ever after" into a gruesome surgical theater where the patient is the female soul.

The film operates in a mode one might call "enchanted realism," a stylistic choice that feels indebted to the saturated, dreamlike decay of 70s European cinema. The kingdom of Swedlandia is not a sanitized Disney park, but a place where the opulent and the grotesque hold hands. Blichfeldt’s camera, often employing uncomfortable zooms and a hazy, soft-focus aesthetic, captures a world that is rotting from the inside out. The production design does not just serve the narrative; it suffocates it. The velvets are too red, the pastries too rich, and the smiles too tight, creating an atmosphere where the pressure to conform feels physically heavy.

At the center of this maelstrom is Elvira, played with fearless, unhinged vulnerability by Lea Myren. Elvira is not simply "ugly" in the Hollywood sense (a beautiful actress in glasses); she is a chaotic force of insecurity, molded by a mother (Ane Dahl Torp) who wields beauty standards like a weapon. Myren’s performance is a high-wire act. She invites us to pity Elvira, then revolt against her desperation, and finally, to see our own complicity in her madness. The body horror elements—the chiseling of a nose, the sewing of eyelashes—are not scares for the sake of scares. They are the logical conclusion of a society that demands women cut away pieces of themselves to fit into a glass slipper, or in this case, a narrow societal mold.

The inevitable comparison is to Coralie Fargeat’s *The Substance*, another recent entry in the "beauty is hell" canon. However, where *The Substance* feels slick and clinical, *The Ugly Stepsister* is messier, earthier, and perhaps more tragic. The horror here isn't just in the gore; it's in the mundanity of the self-hatred. When Elvira resorts to medieval methods to catch the eye of the blandly handsome Prince Julian, the tragedy is not that she fails, but that she believes success would actually save her.

Blichfeldt’s direction ensures that we never forget the physical toll of this ambition. The sound design deserves special mention—the crunch of bone and the squelch of flesh are amplified to nauseating levels, forcing the audience to hear the price of beauty even when they want to look away. Yet, amidst the blood and the satire, there is a profound sadness. The film suggests that the "wicked" stepsister was never born wicked; she was made that way by a world that refused to look her in the eye unless she was pleasing to it.

In the end, *The Ugly Stepsister* is a challenging, often repulsion-inducing watch that refuses to give the audience a comfortable exit. It deconstructs the Cinderella myth not to liberate the princess, but to show us the pile of discarded bodies required to maintain the fantasy. It is a film that demands we look in the mirror and ask not "who is the fairest of them all," but why we care so desperately in the first place.