The Future is a Foreign CountryTime travel cinema often falls into two traps: the intricate puzzle box of paradoxes (à la *Primer*) or the broad, slapstick nostalgia of fish-out-of-water comedies. With *Cycle of Time* (*C'était mieux demain*), director Vinciane Millereau aims for the latter but lands somewhere far more interesting. In her feature directorial debut, Millereau uses the well-worn trope of a time-slip not just to execute pratfalls about smartphones, but to stage a sharp, sociological interrogation of the "good old days."

The premise is deceptively simple, echoing the setup of *Les Visiteurs* but stripping away the medieval chainmail for 1950s petticoats. Hélène (Elsa Zylberstein) and Michel (Didier Bourdon) are the archetypal mid-century couple: he is the breadwinner banker, she is the domestic goddess polishing appliances. When a freak accident involving a washing machine—a brilliant visual metaphor for the "spin cycle" of progress—hurls them into 2025, the film avoids the low-hanging fruit of mere technological confusion. Instead, Millereau focuses on social displacement.

Visually, the film is a tale of two palettes. The 1950s segments are bathed in a Kodachrome warmth, a saturated, almost suffocating coziness that mirrors Hélène's gilded cage. When the action shifts to 2025, the screen is invaded by cold blues, harsh fluorescents, and the sleek, alienating glass of modern Paris. This aesthetic shift isn't just stylistic; it’s narrative. The sterile environment of the future serves as the backdrop for the film’s most potent twist: while Michel withers in this new world, struggling with unemployment and a loss of patriarchal status, Hélène blooms.

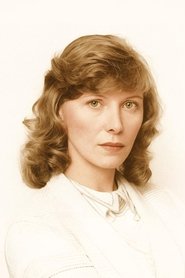

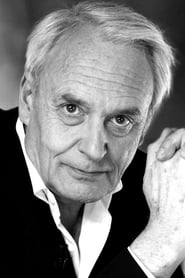

Elsa Zylberstein delivers a performance of nuanced liberation. Watching her Hélène navigate the corporate hierarchy of a modern bank isn't just funny; it’s cathartic. She sheds the "perfect housewife" skin not with hesitation, but with a ravenous hunger for agency. Conversely, Didier Bourdon, often typecast as the grumbling traditionalist, finds a tragicomic depth here. His Michel represents a specific kind of obsolete masculinity, adrift in a society that no longer rewards his default settings. The scene where he attempts to navigate a purely digital job interview—confused not just by the interface, but by the lack of deference shown to him—is painful, hilarious, and deeply human.

The film's "hilarious" marketing tag belies a sharper edge. Millereau doesn't just ask if the past was better; she asks *for whom* it was better. The subplot involving their children, who adapt to the 2025 tech-dystopia with frightening speed, serves as a reminder that nostalgia is often a luxury of the privileged. The "conversation" around this film has rightly focused on its feminist undertones, but it is equally a critique of the modern void—a world where Hélène has power, but where connection is mediated by screens.

*Cycle of Time* is not without its flaws; the third act rushes toward a resolution that feels slightly too tidy for the complex gender dynamics it unpacks. However, it succeeds where many comedies fail: it respects its characters. It doesn't mock the 1950s naiveite nor does it blindly celebrate 2025's progress. Instead, it leaves us with the uncomfortable truth that while we have gained the world in speed and equity, we may have lost the rhythm of living. It is a vibrant, intelligent debut that marks Millereau as a director who understands that the most dangerous time travel isn't through history, but through social class.