The Burden of the UncreatedTo witness the childhood of a god is to witness a horror story, not of jump scares or gore, but of the terrifying dissonance between the infinite and the fragile. In *The Carpenter's Son*, director Lotfy Nathan—best known for the gritty, documentary-style *12 O'Clock Boys* and the Tunisian drama *Harka*—does not give us the golden-haloed Christ of Sunday school felt boards. Instead, drawing from the apocryphal *Infancy Gospel of Thomas*, he offers us a suffocating, dusty, and deeply human examination of a family crushed by a secret too heavy for mortal shoulders. This is not a film about faith as comfort; it is about faith as a haunting.

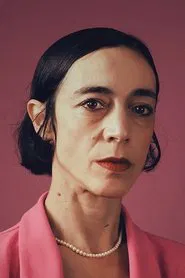

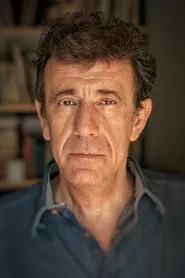

Nathan’s visual language is stripped of the polished sheen typical of biblical epics. Shot on 35mm, the film possesses a tactile grain that makes the heat of Roman-era Egypt feel oppressive. The desert here is not a place of spiritual clarity but a landscape of concealment and paranoia. The camera often lingers on the physical labor of the Carpenter (a subdued, almost feral Nicolas Cage) and the watchful, terrified eyes of the Mother (FKA twigs). The sound design is equally sparse, relying on the wind and the uncomfortable silences of a household where the most important things must never be spoken. When the supernatural does intrude, it is not with a choir of angels, but with a discordant, biological violence that feels closer to Cronenberg than DeMille.

At the center of this storm is Noah Jupe’s "The Boy." Jupe delivers a performance of terrifying vulnerability, portraying a child whose very existence is a volatile weapon he cannot control. The film’s central conflict is not Romans versus Jews, but the internal war within this makeshift family. Cage, shedding his recent penchant for maximalism, plays Joseph as a man disintegrating under the pressure of protecting a divinity he doesn't fully understand. There is a profound tragedy in his attempt to be a father to a son who belongs to the cosmos. The introduction of "The Stranger" (Isla Johnston)—a Satanic figure who tempts the boy not with riches, but with the freedom to be powerful—serves as the catalyst for the film’s most harrowing question: If you had the power to unmake the world, would mercy be your first instinct, or your last?

Ultimately, *The Carpenter's Son* succeeds because it refuses to be a sermon. It treats the Incarnation as a traumatic event—a rupture in the natural order that leaves casualties in its wake. By focusing on the "lost years" of Jesus, Nathan explores the terrifying gap between human morality and divine will. It suggests that the road to salvation was paved not just with good intentions, but with the confusion of a child realizing he is the knife held against the throat of history. It is a challenging, jagged piece of cinema that demands we look at the holy family and see not icons, but refugees hiding from a light too bright to bear.