✦ AI-generated review

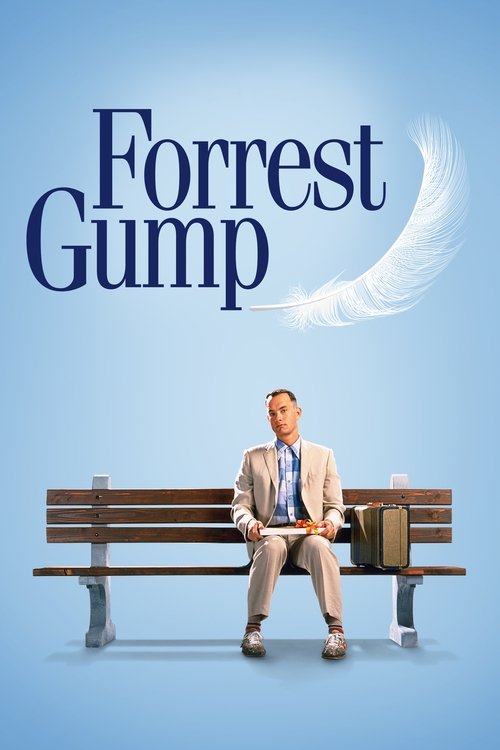

The Feather Weight of History

In 1994, American cinema offered two distinct visions of the national psyche. One was *Pulp Fiction*, a chaotic, violent, adrenaline-fueled deconstruction of morality. The other was *Forrest Gump*, a gentle, nostalgic fable that swept the Academy Awards by offering precisely the opposite: a comforting promise that if you do what you are told and keep running, history cannot hurt you. Decades later, Robert Zemeckis’s magnum opus remains a fascinating, if contentious, Rorschach test for the American experience—a technically dazzling film that treats the turbulence of the 20th century as background scenery for a holy fool.

To understand the film’s enduring power, one must look past its quote-heavy script ("Life is like a box of chocolates") and examine Zemeckis’s visual language. Zemeckis is a technician of the highest order, and here he pioneered "invisible effects." By digitally inserting Tom Hanks into archival footage of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon, Zemeckis achieved something profound: he collapsed the distance between the audience and the untouchable figures of history. However, this technical wizardry serves a specific thematic purpose. By placing Forrest—a man of limited intellect but infinite earnestness—into these moments, the film strips them of their political teeth. The Vietnam War, the Black Panther movement, and the Watergate scandal are rendered toothless, mere obstacles on Forrest’s running path rather than defining moral crises. The camera glides over them with the same slick, Rockwellian sheen that defines the film’s aesthetic.

At the heart of this visual splendor lies a deeply polarized narrative. The film functions as a dichotomy between two characters: Forrest and Jenny (Robin Wright). Forrest represents compliance. He follows orders, joins the army, plays ping-pong, and mows lawns. He is the ultimate blank slate, and for his lack of resistance, the universe rewards him with millions of dollars and a front-row seat to history. Jenny, conversely, represents the counterculture. She questions, she protests, she experiments with drugs and sexual liberation. For her engagement with the turbulent spirit of the '60s and '70s, the narrative punishes her with abuse, addiction, and eventually a fatal illness.

Critics often point to this dynamic as evidence of the film’s conservative undertones—a rejection of the complex social shifts of the era in favor of a "boomer lullaby." Yet, to dismiss the film solely as propaganda is to ignore the crucial third pillar: Lieutenant Dan (Gary Sinise). While Forrest is a fantasy of untouched innocence and Jenny is a tragedy of over-experience, Lt. Dan is the film’s only true human. He rages against God, loses his legs, falls into despair, and eventually finds peace not through blind luck, but through a painful confrontation with his own "destiny." The scene where he shouts at the hurricane from the mast of the shrimp boat is the film’s emotional anchor, providing the raw, existential grit that Forrest’s charmed life lacks.

Ultimately, *Forrest Gump* is a film about the desire to float. The feather that opens and closes the movie symbolizes the film’s central question: "Do we have a destiny, or are we all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze?" Zemeckis suggests we are safest when we float. It is a seductive, beautifully crafted lie about American history—that we can survive the fire without getting burned—but it is told with such technical mastery and heartfelt sincerity that, thirty years later, we are still willing to listen.