The Uncanny Valley of DomesticityThere is a specific, primal anxiety in the collapse of the domestic sanctuary. When the threat comes not from an intruder kicking down the door, but from within the home itself—transmuting a loved one into a lethal predator—the horror becomes intimately violation. Johannes Roberts, a director who has spent his career refining the mechanics of entrapment (most notably in *47 Meters Down*), understands this implicitly. In *Primate*, he strips away the comforts of the modern "animal attack" subgenre, eschewing the glossy safety of CGI for something far more tactile and disturbing. He offers us a film that is less about a killer monkey and more about the fragility of the dominance we assume over the natural world.

Roberts frames the narrative with a deceptive sleekness. We are introduced to the cliffside Hawaiian paradise of Lucy (Johnny Sequoyah) and her family, a space defined by glass, water, and open air. It is a monument to human control over the environment. At the center of this is Ben, the family’s pet chimpanzee. The film takes time to establish Ben not as a prop, but as a member of the family unit, making his eventual rabies-induced descent a tragedy before it becomes a slaughter. When the infection takes hold, Roberts avoids the cartoonish villainy of typical creature features. Instead, he leans into the uncanny; the terror comes from seeing familiar, human-like expressions warped by a viral madness.

Visually, *Primate* is a triumph of spatial awareness. Roberts transforms the sprawling luxury home into a claustrophobic cage. The cinematography utilizes the architecture against the characters—long hallways become kill boxes, and the transparency of glass walls offers visibility without safety. The centerpiece of this tension is the pool sequence, a set piece that rivals the aquatic dread of Roberts’ earlier work. Here, the characters are suspended in water, trapped between the risk of drowning and the absolute certainty of violence waiting at the pool's edge. It is a masterclass in static tension, proving that movement is not required for momentum.

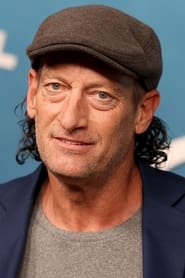

Crucially, the film’s sound design deserves specific praise, particularly in how it navigates the perspective of Lucy’s father, played by Troy Kotsur. By dropping the audio to near-silence during his sequences, Roberts forces the audience into a state of hyper-vigilance. We are denied the auditory cues that usually signal a jump scare, leaving us as vulnerable as the character. It is a respectful and terrifying utilization of Kotsur’s performance, which anchors the film’s emotional stakes.

The decision to rely heavily on practical effects and suit performance for Ben gives the film a weight that digital effects simply cannot replicate. There is a physical presence to the chimp—a heaviness to his movement and a wet, matted reality to his fur—that grounds the horror in the physical realm. When violence occurs, it is messy, difficult, and shockingly brutal. This is not the sanitized violence of a blockbuster; it is mean-spirited and raw, reminiscent of the unforgiving nature of 1980s horror cinema like *Cujo* or *Link*.

Ultimately, *Primate* succeeds because it refuses to wink at the audience. It treats its absurdity with dead seriousness. In an era where horror often apologizes for itself with irony, Roberts delivers a straight-faced, ruthless examination of nature reclaiming its territory. It is a reminder that we are only ever guests in the animal kingdom, and sometimes, the landlord comes to collect.