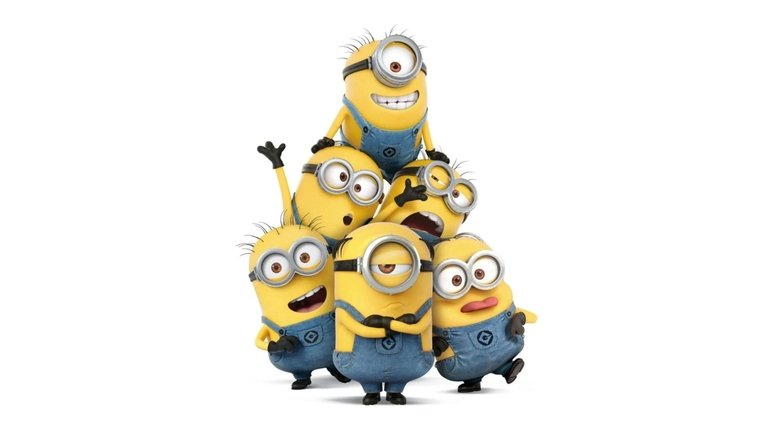

The Gilded Cage of AbsurdityTo dismiss the Minions as mere merchandise fodder is to ignore the nihilistic joy that Pierre Coffin has cultivated for nearly two decades. In *Minions & Monsters*, the third standalone entry in this gibberish-spouting saga, Coffin returns to the director's chair not to reinvent the wheel, but to set it on fire and roll it down a hill. While the film is ostensibly a family comedy about our yellow anti-heroes attempting to conquer 1930s Hollywood, it functions more effectively as a chaotic satire of the creative process itself. This is not just a sequel; it is a fever dream of ambition and failure, wrapped in denim overalls.

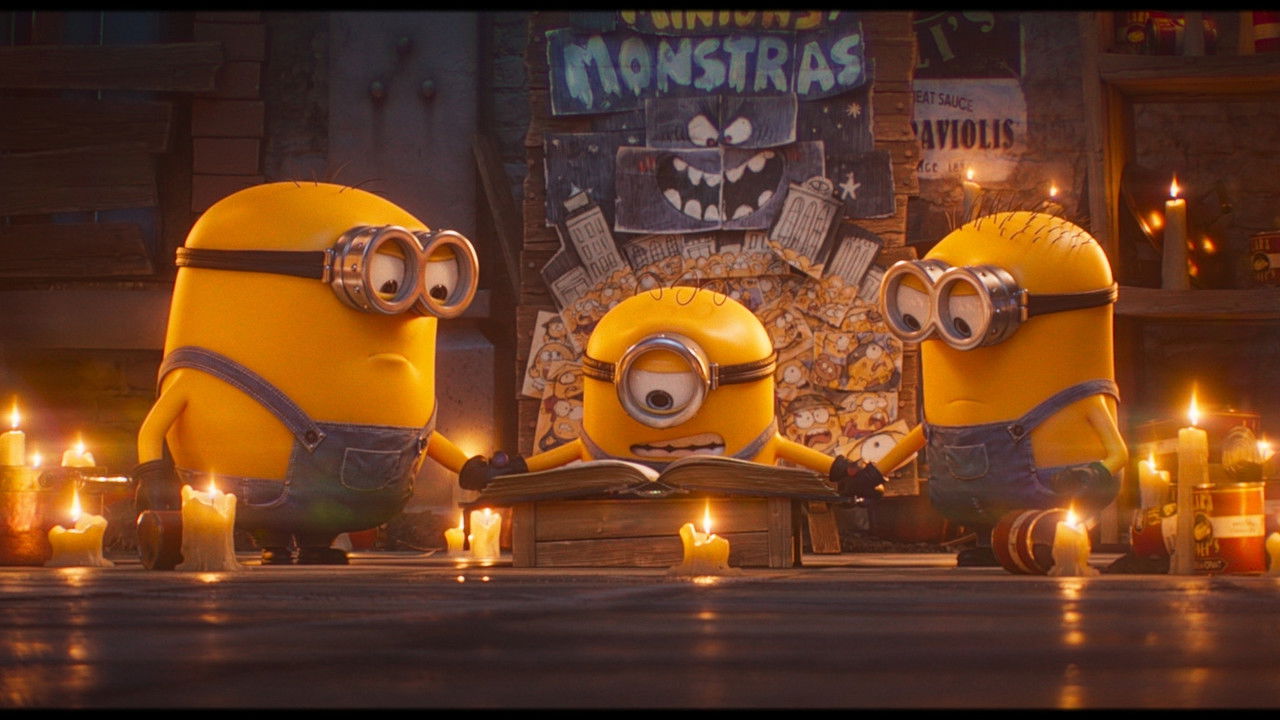

Visually, *Minions & Monsters* is Illumination’s most texture-rich offering to date. Coffin and his team have moved away from the pristine, plastic sheen of previous entries, embracing a noir-adjacent aesthetic that suits the film’s Golden Age of Hollywood setting. The lighting is moodier, the shadows longer, and the monsters—when they inevitably arrive—are rendered with a delightful grotesquerie that recalls the practical effects of Ray Harryhausen. The sound design, too, deserves praise; the juxtaposition of the Minions' high-pitched "Banana" dialect against the guttural, earth-shaking roars of eldritch horrors creates a sonic comedy that lands in every scene.

However, the film’s true strength lies in its surprising thematic weight. The narrative hook—Minions using a spellbook to summon "real" monsters because they can’t afford special effects—is a biting commentary on the industry’s hunger for spectacle at any cost. There is a palpable sense of desperation in Kevin, Stuart, and Bob this time around. They are no longer content to serve a master; they want to *be* the masters of the screen. This shift from henchmen to auteurs provides the film's emotional spine. When their summoning ritual goes wrong, unleashing a Cthulhu-esque entity that cares little for studio contracts, the chaos feels deserved, almost karmic.

Ultimately, *Minions & Monsters* succeeds because it refuses to take its own stakes seriously while treating its characters’ incompetence with utmost respect. It doesn’t have the heartfelt family dynamics of *Despicable Me*, but it replaces sentimentality with a pure, unadulterated anarchic spirit. It serves as a reminder that in a cinema landscape obsessed with logic and lore, there is still immense value in the art of the pratfall. Coffin has crafted a film that is as nonsensical as it is entertaining—a monstrously good time that proves these little yellow agents of chaos are far from past their prime.