✦ AI-generated review

The Velocity of Empty Dreams

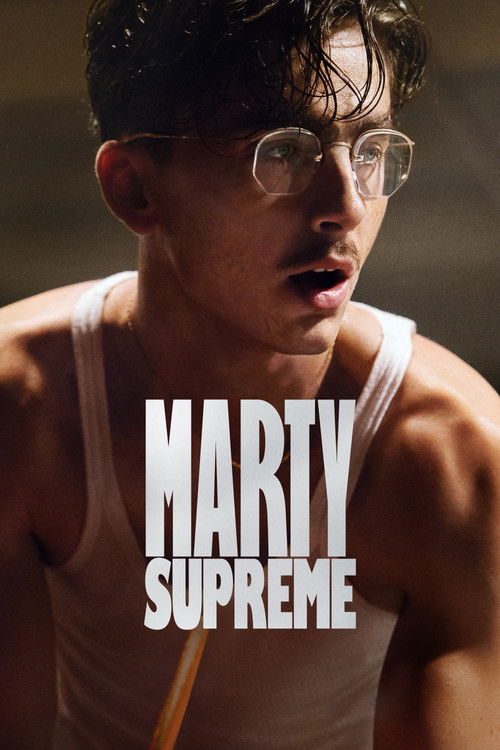

We are accustomed to seeing the American 1950s through a lens of lacquer and chrome—a sedate, pastel-colored era of post-war conformity. In *Marty Supreme*, director Josh Safdie takes a hammer to that vitrine, shattering the glass to reveal the sweaty, desperate pulse beating underneath. This is not the Eisenhower era of white picket fences; it is a fever dream of ambition, played out at the speed of a ping pong ball smashing against a table. Safdie’s first solo outing without his brother Benny is a ferocious, anxiety-inducing masterpiece that reframes the American Dream as a hustle where the only crime is stopping for a breath.

From the opening frames, shot on gritty 35mm by Darius Khondji, the film establishes a visual language that is deliberately disorienting. We are technically in 1952, yet the camera moves with the jittery, handheld panic of 1970s New Hollywood, and the soundtrack pulses with anachronistic 1980s synth-pop. This temporal dissonance is brilliant: it unmoors us, forcing us to feel the timeless nature of Marty Mauser’s (Timothée Chalamet) toxicity. The ping pong matches are not treated as parlor games but as gladiatorial combat. The sound design amplifies the *pock-pock* of the ball into gunshots, creating a suffocating soundscape that mirrors the chaos inside Marty’s head.

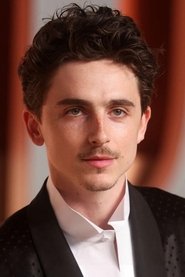

At the center of this hurricane is Chalamet, delivering a performance that is nothing short of career-defining. Physically transforming into "The Needle"—skeletal, moustachioed, and vibrating with nervous energy—he sheds his usual boyish charm for something far more reptilian. His Marty Mauser is a man who believes confidence is currency, a hustler who will steal from his own boss (a weary Larry Sloman) just to buy a plane ticket to a championship he hasn’t qualified for.

What makes the performance profound, however, is the hollowness Chalamet allows us to glimpse behind the bravado. In the widely discussed "Ritz scene," where Marty orders beef Wellington and caviar he cannot afford, he isn’t just scamming the establishment; he is desperately trying to fill a spiritual void with material excess. He is a shark who will drown if he stops moving, yet he has no idea where he is swimming to.

Safdie balances this frenetic energy with surprising moments of gravity. The much-debated "honey scene," where Marty’s rival Bela Kletzki recounts a haunting Holocaust survival story while Marty is busy eyeing a potential conquest, serves as a brutal indictment of the protagonist’s narcissism. Marty hears the words, but he doesn't *listen*; his ambition has rendered him deaf to human suffering. It is a chilling sequence that elevates the film from a sports comedy to a tragic character study.

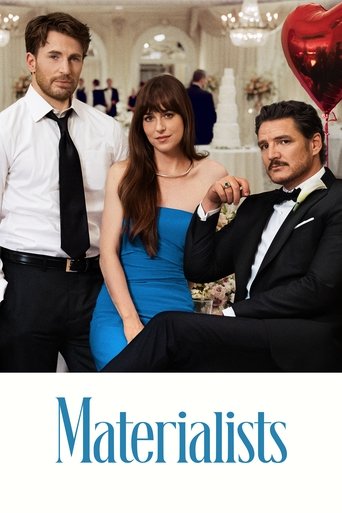

The supporting cast provides necessary friction to Marty’s slide into oblivion. Gwyneth Paltrow, in a triumphant return to the screen, plays fading starlet Kay Stone not as a victim of Marty’s charms, but as a bored predator who recognizes a fellow grifter. Her weary glamour creates a fascinating counterweight to Chalamet’s manic desperation. Meanwhile, the stunt casting of Kevin O’Leary as a shark-like businessman pays off unexpectedly, blurring the lines between the film’s 1950s setting and our modern obsession with transactional relationships.

*Marty Supreme* is a relentless, exhausting experience, but that is precisely the point. By the time the final match concludes—a blur of motion that leaves the audience as breathless as the players—we are left with the distinct aftertaste of melancholy. Safdie has crafted a "propulsive epic" that celebrates the hustle while mourning the soul lost in the process. It is a film that argues greatness is possible, but the price of admission is everything you are.