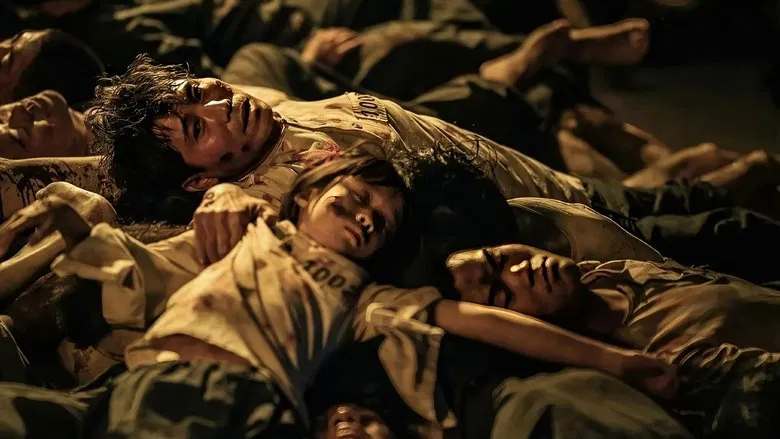

The Weight of MemoryTo confront the horrors of Unit 731 is to stare into an abyss where science was stripped of its conscience and humanity was reduced to raw data. For decades, this chapter of World War II—where the Japanese Imperial Army conducted lethal biological experiments on civilians in Northeast China—has remained a festering wound in historical memory. Zhao Linshan’s *731* (internationally titled *Evil Unbound*) arrives in 2025 not merely as a war film, but as a cinematic "courtroom of justice," explicitly released on the anniversary of the Mukden Incident. Yet, while the film carries the heavy burden of witnessing, it ultimately stumbles under the weight of its own theatricality, leaving us to question whether the gloss of modern production enhances or obscures the gritty reality of the past.

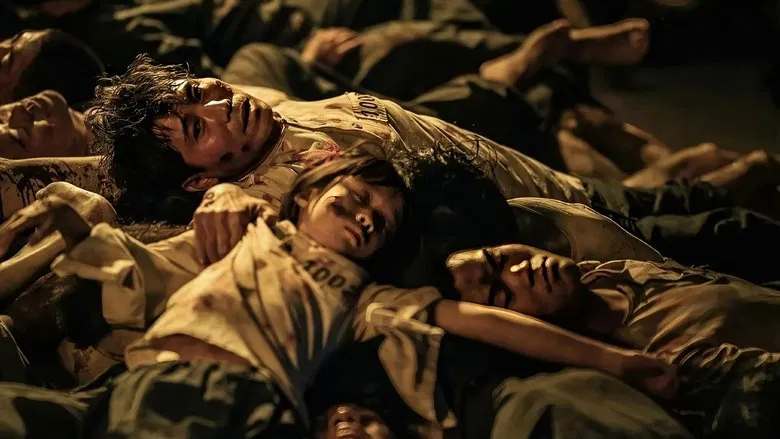

From a visual standpoint, Zhao constructs a world that is suffocatingly cold. The cinematography leans heavily into a desaturated palette of steel grays and snow whites, punctuated only by the jarring crimson of blood and the sterile white of lab coats. This is a deliberate stylistic choice, creating a visual language of isolation. The vast, frozen landscapes of Heilongjiang are not just a setting but a prison, emphasizing the hopelessness of the "maruta"—the dehumanizing term ("logs") used for the victims. However, the film’s reliance on polished, high-contrast aesthetics occasionally betrays its subject matter. There are moments where the CGI enhancements feel too pristine, creating a distance between the audience and the visceral horror of the experiments. Unlike the raw, almost unwatchable grit of the 1988 film *Men Behind the Sun*, Zhao’s lens sometimes feels too safe, prioritizing cinematic composition over the chaotic ugliness of truth.

The narrative anchor is Wang Yongzhang (played by Jiang Wu), an ordinary vendor whose descent into this hellscape serves as the audience's entry point. The film attempts to humanize the statistics by focusing on the camaraderie and desperate resilience of the prisoners. Here, the film struggles with a tonal imbalance. In an effort to create moments of hope or defiance, the script occasionally veers into melodrama that feels at odds with the clinical cruelty of the setting. The performances are committed, particularly Jiang Wu, who conveys a crumbling stoicism that is heartbreaking to watch. Yet, the character arcs are often undercut by dialogue that feels designed for a modern audience's sensibilities rather than grounding us in the terrifying uncertainty of 1940s captivity. The internal struggle—the fight to remain human when treated as a specimen—is powerful, but it is frequently interrupted by scenes that feel performative rather than authentic.

Ultimately, *731* occupies a complicated space in modern cinema. It is a necessary film in terms of subject matter, demanding that the world acknowledge atrocities that have often been overshadowed by other wartime narratives. However, as a piece of art, it is caught between the desire to be a somber historical document and a gripping survival thriller. The director’s ambition to create a "courtroom" is noble, but true justice in art requires a fearless confrontation with the complex, unpolished nature of evil. *731* succeeds in reminding us of the pain, but it falls short of making us truly feel the suffocating silence of those who were lost to the frost. It is a memorial etched in ice, but one that perhaps needed more fire to truly burn itself into the cinematic consciousness.