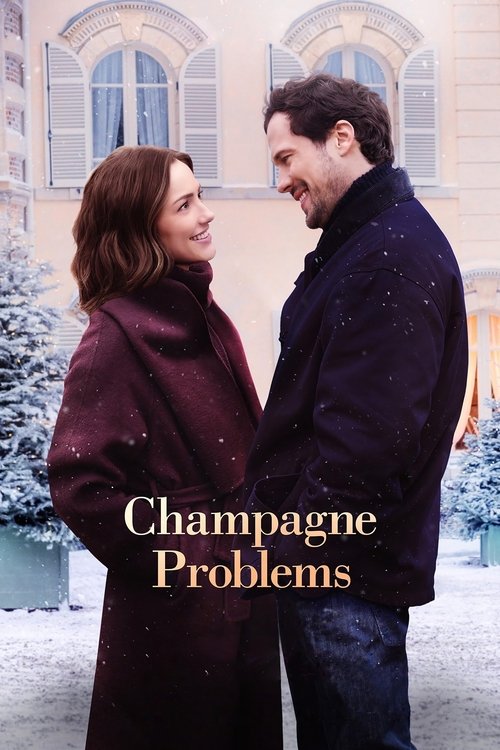

The Effervescence of IllusionThere is a moment in Mark Steven Johnson’s *Champagne Problems* (2025) that betrays the film’s glossy, algorithmic exterior. Sydney Price (Minka Kelly), a corporate acquisition shark whose ambition is usually signaled by the tightness of her ponytail, stands amidst the golden-hour glow of a French vineyard. She is there to liquidate a legacy; she stays to fall in love. It is a narrative beat as old as the genre itself, yet Johnson—a filmmaker who has curiously migrated from the leather-clad angst of *Daredevil* and *Ghost Rider* to the soft-focus comfort of Netflix holiday romances—frames it with a sincerity that almost hurts. The film, much like the bubbly beverage it fetishizes, offers a fleeting, intoxicating escape, even if we know the headache that awaits us in the real world.

To dismiss *Champagne Problems* as merely "content" to be consumed while wrapping gifts is to ignore the specific visual language Johnson is attempting to refine. Having moved on from *Love in the Villa*, he seems determined to perfect the "tourism core" aesthetic. The cinematography here is not just bright; it is aggressive in its luminosity. Paris is not a city of grit or traffic, but a series of postcards stitched together by an unseen hand. The camera glides over the Seine and through the vineyards of Champagne with a smoothness that suggests a world without friction. This visual suffocation—where every room is perfectly lit and every coat is perfectly tailored—serves as a metaphor for Sydney’s internal state. She is a woman who has optimized her life to the point of sterility, and the messy, organic chaos of the Cassell family vineyard is the necessary antidote.

However, the film’s true conflict is not between Sydney and the handsome, brooding heir Henri (Tom Wozniczka), but between the authentic and the manufactured. The script posits a battle for the soul of Château Cassell: should it remain a family endeavor or become a portfolio asset for "The Roth Group"? It is ironic, then, that the film itself is a product of the Netflix machine, arguably the "Roth Group" of modern cinema.

Minka Kelly anchors this contradiction with a performance that is surprisingly tender. In scenes where she must choose between her career and her conscience, she allows a flicker of genuine fatigue to break through her polished veneer. She plays Sydney not as a villain redeemed by love, but as a survivor of late-stage capitalism looking for an exit ramp. Her chemistry with Wozniczka is serviceable, but the real emotional weight comes from Thibault de Montalembert (of *Call My Agent!* fame) as the patriarch Hugo. He brings a gravitas to the role that elevates the material, reminding us that behind every "legacy brand" are human hands and human grief.

The film stumbles in its reliance on broad caricatures—Flula Borg’s eccentric German investor feels like he wandered in from a different, louder movie—but it recovers in its quieter moments. The scenes inside Henri's dream bookstore, a sanctuary of paper and ink, suggest a reverence for tangible things in a digital age.

Ultimately, *Champagne Problems* is a film about the desire to be "un-acquired." In a year where cinema is fighting for its soul against franchises and algorithms, Johnson delivers a story about a small, beautiful thing resisting absorption by a giant, indifferent entity. That the movie itself is a standardized unit of streaming entertainment is the final, sparkling irony. It goes down smooth, sweet, and uncomplicated, leaving you with a lingering wish that life could be resolved as easily as a third-act misunderstanding under the Parisian lights.