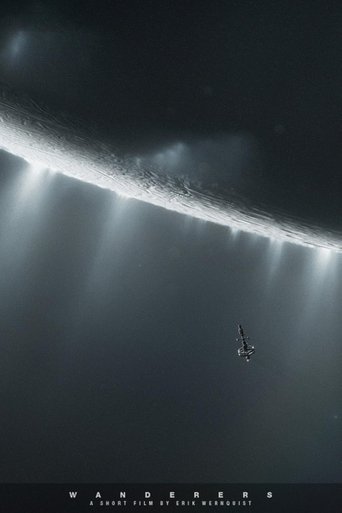

The Architecture of EmpathyIn the modern cinematic landscape, the desire to escape the human condition is often rendered through explosive spectacle or dystopian grimness. We build machines to destroy us or to save us, but rarely to simply *understand* us. Daniel Chong’s *Hoppers* (2026) arrives as a curious, vibrant rebuttal to this trend. Ostensibly a family comedy about a girl transferring her consciousness into a robotic beaver, the film quickly reveals itself to be a far more tender exploration of dysphoria and connection. Chong, best known for the gentle, awkward camaraderie of *We Bare Bears*, brings that same humanistic lens to Pixar, crafting a film that asks not just what it means to be an animal, but what it takes to be present in one's own life.

The premise is high-concept sci-fi distilled into whimsical farce: scientists have unlocked the ability to "hop" human minds into animatronic fauna. For Mabel (Piper Curda), a young woman for whom the noise of human society has become deafening, the technology offers more than scientific discovery; it offers a fugue state, a vacation from the self. Chong frames the early laboratory scenes not with the sterile coldness of a thriller, but with the chaotic energy of a startup run by dreamers. However, the film truly breathes when Mabel wakes up in the fur and circuitry of a beaver.

Visually, *Hoppers* is a triumph of restraint. In an era where animation often chases the uncanny valley of hyper-realism, Chong and his art department utilize what they’ve dubbed the "Paintbrush tool," a rendering technique that simplifies background textures into impressionistic strokes. This is not merely an aesthetic choice; it is narrative functionalism. By softening the world, the film mimics the sensory shift Mabel experiences—reality becomes less sharp, more fluid, and strangely, more true. The forest doesn't look like a photograph; it looks like a memory of nature, idealized and inviting.

The heart of the film, however, beats in the strange, bureaucratic society of the animals themselves. We are introduced to King George (Bobby Moynihan), a beaver monarch who rules not with an iron fist but with a distinctively nervous energy. The dynamic between Mabel—hiding her human intellect inside a clumsy robot body—and George provides the film’s comedic engine, yet it also drives its central tragedy. Mabel is an impostor in Eden. The film navigates the environmental stakes—a construction project led by the slick Mayor Jerry (Jon Hamm) threatening the habitat—without descending into preachy didacticism. Instead, the ecological threat serves as a mirror to Mabel's internal conflict: the fear of losing a sanctuary she never truly belonged to in the first place.

There is a pervasive "weirdness" to *Hoppers* that feels refreshing for a studio that occasionally plays it safe. The humor is idiosyncratic, relying less on pop-culture references and more on the absurdity of biology and social hierarchy. Yet, beneath the jokes about beaver protocols and "janky" robot movements, there is a profound melancholy. The technology that allows Mabel to connect with nature ultimately highlights her separation from it. She is observing the sublime through a lens of wires and data.

Ultimately, *Hoppers* succeeds because it refuses to treat its sci-fi conceit as a gimmick. It uses the barrier of the robot suit to dismantle the barriers Mabel has built around her own heart. It is a film about the clumsy, imperfect, and often hilarious attempts we make to find our "tribe," whether that community walks on two legs or four. In a digital age where we all project avatars of ourselves into the void, Chong suggests that the most radical act is not hopping into a new body, but being comfortable in the one we have.