The Architecture of ExhaustionThere is a moment in *Padre no hay más que uno 5: Nido repleto* where Javier (Santiago Segura) stands in the hallway of his overcrowded home, buffeted by the cacophony of his adult children, their partners, and the extended family that refuses to leave. The camera lingers on him not as the frantic patriarch of the earlier films, but as a man visibly eroding under the weight of his own creation. It is a fleeting shot, perhaps unintentional in its gravity, but it betrays the film’s true subject: not the joy of family, but the suffocating inability to move forward.

Santiago Segura, a director who once redefined Spanish cinema with the grotesque satire of *Torrente*, has spent the last decade constructing a very different kind of fortress. His *Padre* saga has become a box-office annuity, a reliable machine that prints tickets by reflecting the anxieties of the Spanish middle class back at them with a softening filter. In this fifth installment, however, the filter is wearing thin. The premise—that the children, now grown, refuse to leave the nest—shifts the genre from family sitcom to a mild form of domestic horror. The house, once a playground for childhood antics, has become a claustrophobic ecosystem where privacy is extinct and maturity is indefinitely postponed.

Visually, Segura shoots the film with the bright, flat lighting of a television commercial, a choice that feels increasingly discordant with the script’s underlying tension. The "Nido Repleto" (Full Nest) of the title is rendered as a space of constant, overlapping motion. Scenes are packed with bodies, the frames cluttered with the detritus of too many lives lived in too few square meters. It creates a sensory overload that mimics the characters' stress, though one suspects this is less a stylistic choice and more a necessity of wrangling an ensemble cast that has ballooned to unmanageable proportions. The visual language effectively traps the viewer; there is literally nowhere to look that isn't occupied by a family member demanding attention.

At the heart of the film lies a generational conflict that Segura approaches with surprising weariness. The children are no longer cute agents of chaos; they are distinct personalities exhibiting a failure to launch that feels culturally specific to modern Spain, where economic precarity often forces multi-generational cohabitation. Yet, the script, co-written by Segura and Marta González de Vega, retreats from the sharper edges of this reality. Instead of exploring the genuine frustration of a generation unable to afford independence, the film falls back on the familiar crutch of the "man-child" trope—extending it now to the actual children.

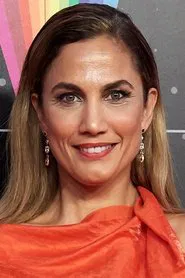

Toni Acosta, returning as Marisa, remains the film’s anchor, playing the straight woman with a resilience that borders on the heroic. Her chemistry with Segura is lived-in and effortless, providing the film with its few moments of genuine warmth. However, the introduction of more peripheral characters—in-laws, boyfriends, eccentric neighbors—dilutes the core dynamic. The narrative becomes episodic, a series of sketches stitched together rather than a cohesive story. We drift from one misunderstanding to another, the stakes never rising above the level of a sitcom dilemma.

Ultimately, *Padre no hay más que uno 5* suffers from the very syndrome it attempts to satirize: it doesn't know when to let go. It is a film that exists because the market demands it, not because the story requires it. Segura has proven he understands the pulse of the audience better than almost any working director in Spain, but in filling the nest to capacity, he has left no room for the story to breathe. We leave the theater not with a sense of closure, but with the distinct feeling that we, like Javier, are trapped in a loop of diminishing returns, waiting for a quiet that never comes.