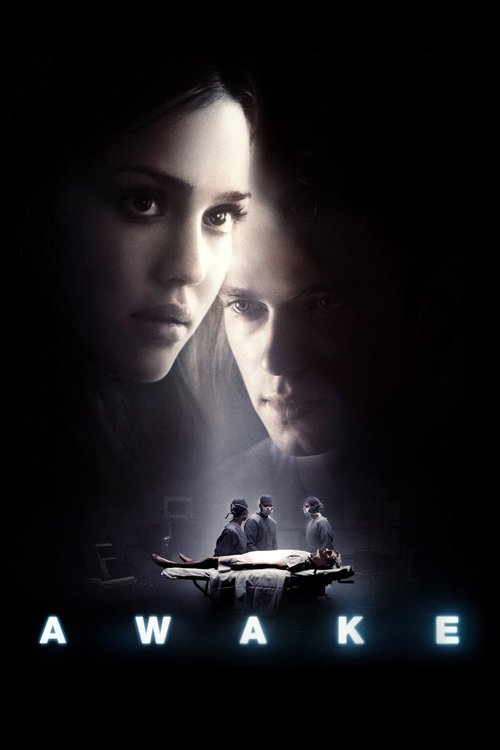

The Anatomical Theatre of BetrayalThere is a specific, primal coordinate of human terror that lies in the space between consciousness and agency. We fear the loss of control more than pain itself. Joby Harold’s 2007 directorial debut, *Awake*, serves as a fascinating, if melodramatic, exploration of this fear. While contemporary critics largely dismissed the film as a pulp thriller, and medical professionals decried its inaccuracies regarding "anesthetic awareness," to view *Awake* merely as a medical procedural is to miss its operatic ambition. It is not a documentary on surgical failure; it is a heightened Greek tragedy performed in scrubs, where the protagonist’s paralysis becomes a cruel metaphor for his blindness to the treacheries of his own life.

The film introduces us to Clay Beresford (Hayden Christensen), a young billionaire whose life is a glossy veneer of wealth and secret romance. When he undergoes a heart transplant, the anesthesia fails to sedate his mind, leaving him physically frozen but mentally screaming as the scalpel breaks skin. Harold uses this terrifying premise—the "locked-in" state—to strip away the protagonist's privilege. In the sterile, fluorescent glare of the operating theater, Clay is no longer a master of the universe; he is meat. The director’s visual language shifts from the warm, golden hues of Clay's romantic life to cold, clinical blues and harsh whites, creating a suffocating sense of reality that presses against the lens.

As Clay lies helpless, his internal monologue becomes our only guide, a narrative device that could have been clunky but instead emphasizes his utter isolation. Critics often deride Christensen’s performance as wooden, yet here, his restrained affect works in the film’s favor. Before the surgery, Clay is a man sleepwalking through his own existence, naive to the machinations around him. It is only when he is literally paralyzed that he paradoxically "wakes up" to the truth. The film cleverly utilizes an out-of-body narrative device—Clay’s consciousness roaming the hospital corridors—to allow him to witness the conspiracy unfolding against him. This liminal space, where Clay is a ghost in his own life, visualizes the dissociation of trauma.

The true emotional weight of the film, however, rests not on the romance with Jessica Alba’s deceptively sweet Sam, but on the shoulders of Lena Olin as Clay’s mother, Lilith. In a genre often populated by disposable supporting characters, Olin delivers a performance of ferocity and grace. The narrative initially frames her as the overbearing, possessive matriarch—a Freudian obstacle to Clay's happiness. Yet, as the conspiracy of the "trusted" doctors and the lover is revealed, the film subverts our expectations. The "monster" mother is revealed to be the only guardian of truth in a world of smiling liars.

The film’s climax moves beyond the medical thriller into the realm of sacrificial myth. The physical heart being transplanted becomes a heavy symbol for the emotional heart being broken and then restored. The betrayal Clay suffers is total—institutional, romantic, and fraternal—and the surgery becomes a violent externalization of this internal dismantling. The script forces us to ask: who truly loves us? The one who whispers sweet nothings while plotting our demise, or the one who is willing to destroy themselves to keep our blood pumping?

Ultimately, *Awake* succeeds not because it is realistic, but because it is unapologetically cynical about human greed and fiercely idealistic about maternal love. It plays out like a modern Grand Guignol, using shock and visceral horror to arrive at a sentimental truth. It suggests that sometimes, we must be cut open and immobilized before we can see the world for what it truly is.