The Architecture of FailureIn the lexicon of American cinema, the heist film is usually a study in competence. We watch, breathless, as professionals manipulate time and technology to subvert systems of power. But Kelly Reichardt, the quiet poet of the Pacific Northwest and now the New England suburbs, has never been interested in competence. With *The Mastermind* (2025), she takes the genre’s rigid skeleton—the plan, the crew, the execution, the getaway—and gently dissolves it in the humid air of 1970 Massachusetts. The result is not a thriller, but a tragedy of mediocrity; a portrait of a man who mistakes his own restlessness for genius.

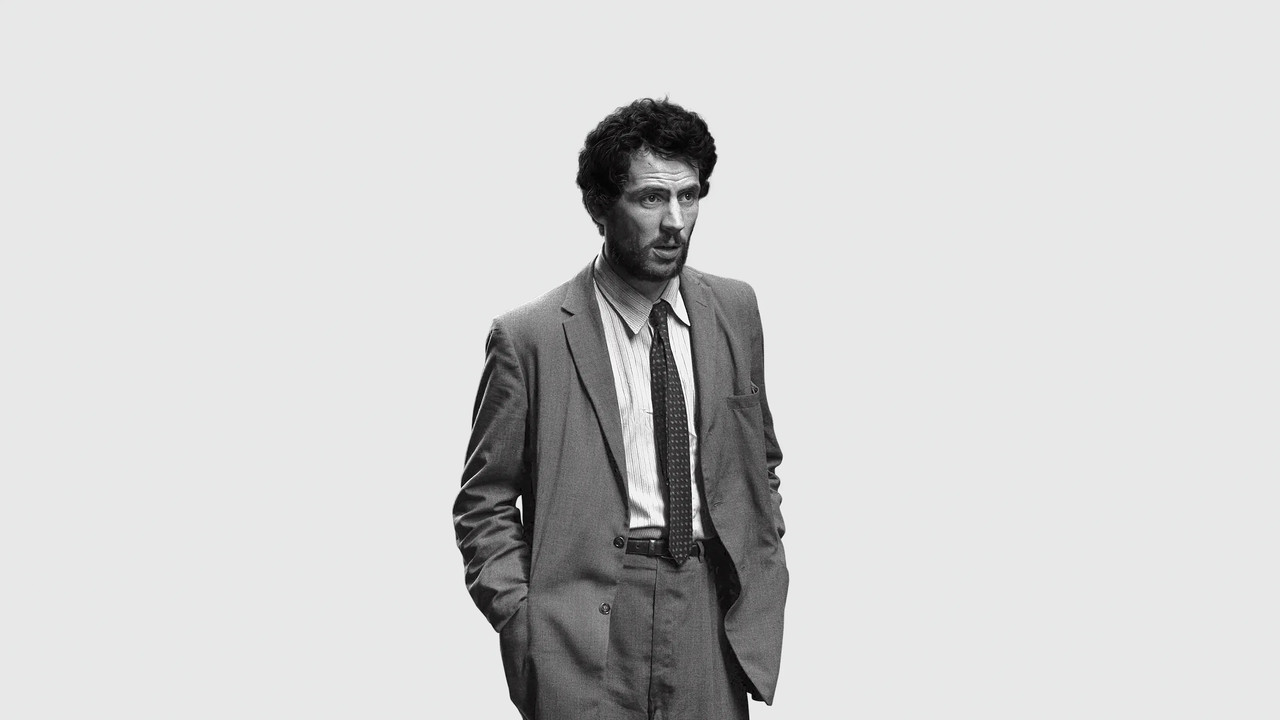

Reichardt’s lens, operated by her longtime collaborator Christopher Blauvelt, captures the era not through garish needle drops or bell-bottom clichés, but through a suffocating beige stillness. The film looks like a faded Polaroid found in a drawer—mute browns, dusty sunlight, and the overwhelming texture of wood paneling. This visual language serves the story’s central irony: J.B. Mooney (Josh O'Connor) views himself as a protagonist in a high-stakes drama, yet the world around him remains stubbornly mundane. The camera rarely moves to match his internal agitation; instead, it observes him with a static, almost judicial detachment, trapping him in the very domestic spaces he is desperate to transcend.

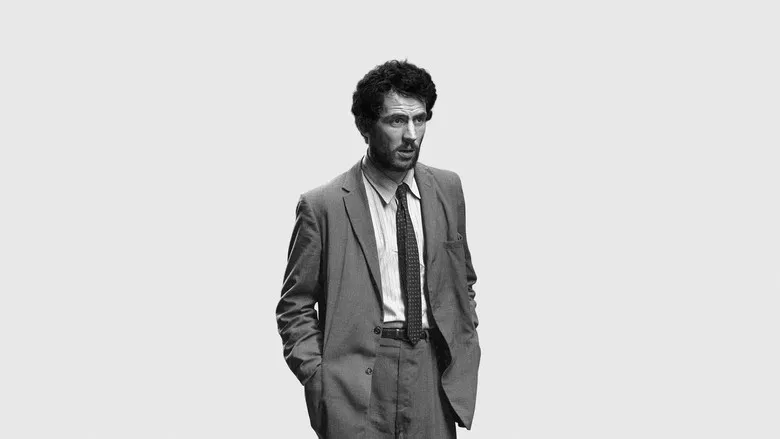

The heart of the film lies in O'Connor’s precipitous performance. As J.B., he sheds the brooding charisma of his past roles for a sweaty, nervous energy that is painful to watch. He is a man who "lives for the narrative," as one critic noted, treating his wife Terri (Alana Haim) and their children not as family, but as props in his self-mythology. The heist itself—a clumsy theft of Arthur Dove paintings from a sleepy local museum—is executed with such lack of grace that it becomes a dark comedy of errors. Yet, Reichardt refuses to let us laugh *at* him entirely. In J.B.’s frantic improvisation, we see the terrifying vulnerability of a man realizing, in real-time, that he is not the exception to the rule.

A pivotal sequence involving J.B.’s old friends, Fred (John Magaro) and Maude (Gaby Hoffmann), exposes the film’s moral weight. When J.B. arrives seeking sanctuary, the collision between his delusional criminal fantasy and their grounded, ethical reality is devastating. It is here that the Vietnam War backdrop moves from ambient noise to thematic text. While the country bleeds abroad and protests erupt at home, J.B.’s selfish "rebellion" is revealed as nothing more than privileged escapism. He isn't fighting the system; he is simply refusing to participate in the adult world.

Ultimately, *The Mastermind* is an anti-heist film that steals the audience’s expectation of closure. There is no blaze of glory, only the slow, agonizing friction of consequences. Reichardt suggests that the true crime isn't the theft of the art, but the theft of peace from those who loved J.B. enough to trust him. It is a quiet devastation, a film that whispers its verdict rather than shouting it, leaving us to contemplate the heavy cost of a life lived entirely for oneself.