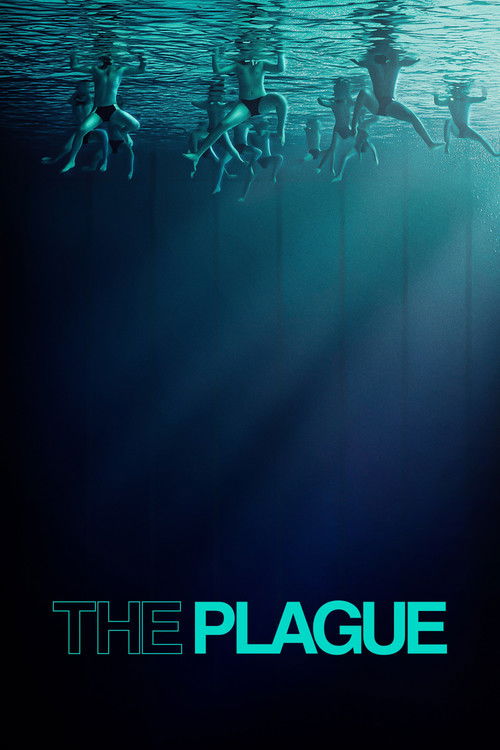

The Chlorine Stench of CrueltyAdolescence is rarely the golden hour of innocence that nostalgia merchants would have us believe. It is, more often, a visceral state of emergency—a time when the body betrays you, social hierarchies are enforced with fascistic precision, and the desperate need to belong can drive a child to commit acts of unthinkable callousness. In *The Plague*, director Charlie Polinger captures this terrifying frequency with a precision that borders on the sadistic. This is not merely a coming-of-age drama; it is a horror film where the monster is not a slasher in the woods, but the suffocating pressure of masculinity in its embryonic, toxic form.

Polinger, making a confident and unsettling feature debut, transports us to the humid, echoing chambers of a water polo camp in 2003. The setting is masterfully chosen. An indoor pool is a place of distortion—sounds are amplified, vision is blurred by chlorine and humidity, and the body is terrifyingly exposed. From the opening sequence, Polinger’s camera, often submerged, treats the water not as a place of play, but as a combat zone. We see thrashing limbs, silent screams, and the constant, rhythmic struggle to keep one’s head above the surface—a perfect visual metaphor for the social drowning occurring above the waterline.

The narrative centers on Ben (played with heart-wrenching vulnerability by Everett Blunck), a socially anxious arrival who quickly realizes that the camp is governed by a ruthless caste system. At the top is Jake (Kayo Martin), a bully whose cruelty is masked by a terrifyingly charismatic smile. At the bottom is Eli, a boy suffering from severe eczema, which the other campers have mythologized into a contagious "plague." The film’s tension arises not from whether Ben will survive the physical demands of the sport, but whether his moral compass can survive his proximity to power. Watching Ben slowly detach from his own empathy to avoid becoming a target himself is a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions, played out in Speedos and locker rooms.

Polinger’s visual language emphasizes the grotesquerie of this transformation. As the film progresses, the "plague"—initially just a cruel nickname for a skin condition—manifests as a psychosomatic body horror. The camera lingers on rashes, scratches, and the physical manifestations of guilt, turning the teen body into a landscape of trauma. The influence of *Lord of the Flies* is evident, but Polinger strips away the desert island allegory; these boys don’t need to be stranded to turn on each other. They do it under the watchful, yet negligent, eye of their coach (Joel Edgerton), whose failure to intervene serves as a damning indictment of how adult passivity enables youth cruelty.

What makes *The Plague* so difficult to shake is its refusal to offer the audience a comfortable exit. There is no triumphant winning goal, no tearful reconciliation that washes away the sins of the summer. Instead, the film leaves us with the heavy, damp realization that the cruelty learned in these formative years doesn't just vanish; it calcifies. Ben’s journey suggests that the cost of fitting in is often the permanent loss of a piece of one's soul.

In an era of cinema often obsessed with empowering narratives and clear moral binaries, *The Plague* stands out for its bleak honesty. It forces us to remember the specific, nauseating dread of being twelve years old, unprotected, and desperate. It is a film that clings to you like the smell of chlorine—sharp, chemical, and impossible to wash off.