✦ AI-generated review

The Ache Behind the Anthem

There is a distinct, often patronizing genre of cinema dedicated to the "amateur." We usually watch these films with a detached smirk, waiting for the characters to realize they are delusional. But Craig Brewer is not that kind of director. From the sweaty, desperate ambition of *Hustle & Flow* to the joyous resurrection of *Dolemite Is My Name*, Brewer has established himself as the poet laureate of the American underdog—specifically, the artist whose art the world deems "lowbrow." In *Song Sung Blue*, he turns his empathetic lens toward the most easily mocked subculture in entertainment: the tribute band. What follows is a film that begins as a sequined party and ends as a bruising meditation on resilience, proving that the distance between a dive bar and a stadium is measured not in talent, but in the sheer will to survive.

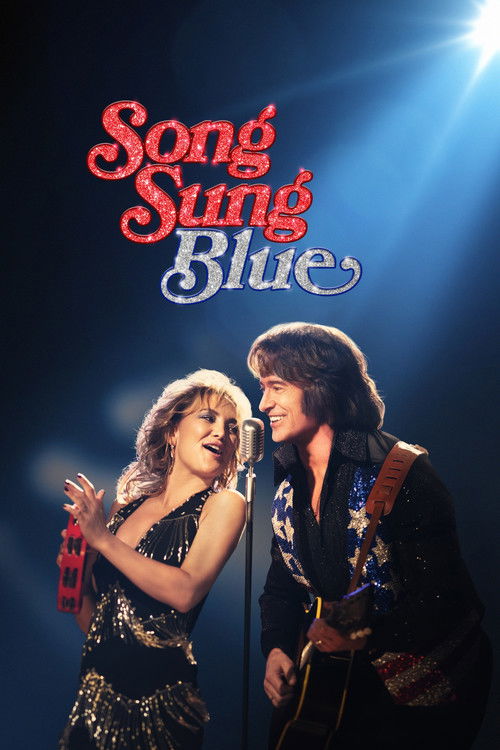

Brewer’s visual language here is a study in textures. He juxtaposes the harsh, gray chill of a Milwaukee winter with the suffocating warmth of stage lights. The costumes—replica Neil Diamond jumpsuits that are just a little too tight, a little too loud—act as armor. Brewer shoots the musical numbers not as campy spectacles to be laughed at, but as transcendent religious experiences for the characters. When Mike (Hugh Jackman) and Claire (Kate Hudson) step onto the sticky floor of a local pub as "Lightning & Thunder," the camera swirls with an intoxicating energy that convinces us, if only for three minutes, that they really are superstars. The music of Neil Diamond, often dismissed as kitsch, is reclaimed here as a primal scream of joy for people whose lives have offered them very little of it.

At the film's core is a romance built on shared brokenness. Hugh Jackman, an actor who usually radiates indestructible charisma, impressively scales it back to play Mike, a recovering alcoholic who wears his sobriety like a heavy coat. But it is Kate Hudson who provides the film’s shattering emotional anchor. As Claire, she navigates a character arc that violently pivots from romantic comedy to medical tragedy. The widely discussed "tonal shift" in the film’s second half—sparked by a freak accident that leaves Claire physically altered and deeply depressed—has been divisive. Critics have called it jarring, a "Hallmark movie" turn. However, to dismiss this shift is to misunderstand Brewer’s intent. He is arguing that for the working class, tragedy doesn't wait for the third act; it interrupts the chorus.

The narrative admittedly struggles to keep its footing during these darker sequences. The script sometimes rushes through Claire’s recovery, glossing over the psychological toll in favor of getting the band back together. Yet, the film succeeds because it refuses to treat the "tribute band" dream as a consolation prize. When the duo performs "Sweet Caroline," it isn't portrayed as a sad echo of the real thing; it is presented as a valid, vital act of creation. The "conversation" around the film often fixates on whether it’s a comedy or a drama, but *Song Sung Blue* sits uncomfortable in the gap between the two—much like the Neil Diamond songs it reveres, which often hide profound loneliness behind a catchy melody.

In an era of polished, intellectual property-driven cinema, *Song Sung Blue* feels rebelliously uncool. It wears its heart on its rhinestone sleeve. It is a messy, uneven, and deeply human film that suggests our dreams don't have to be original to be real. They just have to be loud enough to drown out the silence.