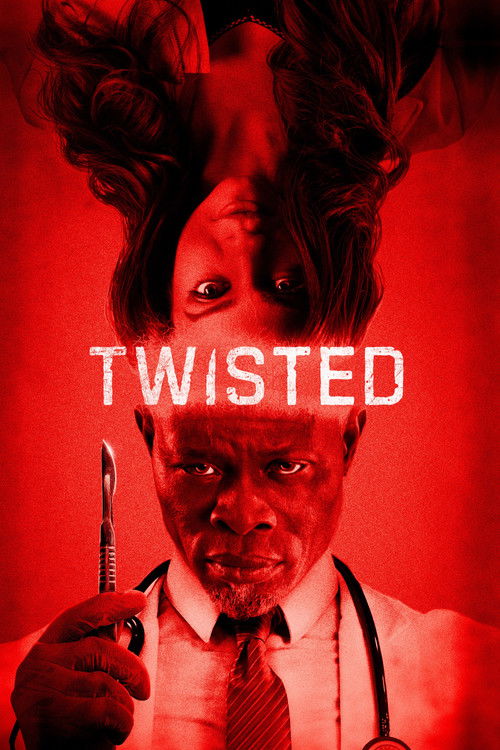

The Architecture of AgonyIn the modern cinematic landscape, the "eat the rich" narrative has become a comfortable, well-worn sweater. We are used to seeing the 1% punished for their excess. However, *Twisted* (2026), the latest claustrophobic nightmare from Darren Lynn Bousman, flips this script with a cruelty that feels distinctly retro. It suggests that in the concrete jungle of New York City, the only thing more dangerous than a desperate grifter is a landlord with a god complex. Bousman, a director who has spent his career examining the mechanics of torture (*Saw II-IV*, *Repo! The Genetic Opera*), here turns his gaze to a more insidious trap: the American housing market.

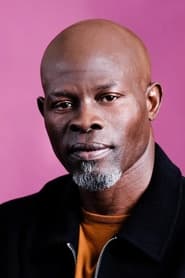

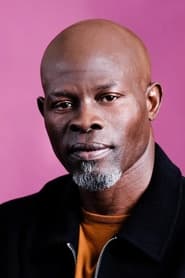

The film introduces us to Paloma (Lauren LaVera) and Smith (Mia Healey), two millennials operating a scam that is as brilliant as it is indicative of our economic anxieties. They lease luxury apartments they don’t own to desperate renters, vanishing with the cash before the keys stop working. LaVera, shedding the pure-hearted "Final Girl" armor she donned in the *Terrifier* franchise, plays Paloma with a sharp, morally grey edge. She is not a victim; she is a predator in a sleek blazer. But the film’s central thesis is that there is always a bigger fish. When they target the sprawling residence of Dr. Robert Kezian (Djimon Hounsou), the genre violently pivots from a slick *Ocean’s Eleven*-style caper into a suffocating chamber drama.

Bousman’s visual language in *Twisted* is a study in deterioration. The film begins with the polished, wide-angle sheen of a high-end real estate listing—crisp, inviting, and deceptive. As Kezian’s trap snaps shut and the power dynamic inverts, the film physically constricts. Bousman and cinematographer Bella Gonzales employ a fascinating, if aggressive, technique: as Paloma’s agency is stripped away, the aspect ratio slowly narrows, and the lighting shifts from naturalistic tones to sickly, hyper-color gels.

By the third act, the audience is looking through a lens that is warped and claustrophobic, mirroring the neurological experimentation Kezian visits upon his captives. This is not merely an aesthetic choice; it is a suffocating representation of madness. The "medical" sequences are less about surgical precision and more about the chaotic dissolution of the self, bathed in neon-soaked dread that recalls the grimiest entries of 90s industrial horror.

The film’s pulse, however, is dictated by the duet between LaVera and Hounsou. Djimon Hounsou brings a terrifying Shakespearean gravitas to Kezian. He does not play the surgeon as a cackling villain, but as a man burdened by a twisted altruism—he believes his horrific experiments are necessary to "save humanity." It is a performance of immense weight that grounds the film’s more exploitation-heavy elements.

Opposite him, LaVera proves she is one of the most dynamic physical actors working in horror today. She matches Hounsou’s intensity not with strength, but with a feral, scraping desperation. The tragedy of *Twisted* is that Paloma’s initial crime—a desire for a space of her own—is punished by a total loss of bodily autonomy.

*Twisted* is not a polite film. It is messy, nasty, and refuses to offer the catharsis that modern audiences have come to expect. It eschews the "good for her" ending in favor of something far bleaker and more resonant. In a year where horror has often played it safe with nostalgia, Bousman delivers a jagged reminders that some leases can only be broken by bone and blood. It is a grim fable about the cost of living, where the price is quite literally your mind.