✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of a Scream

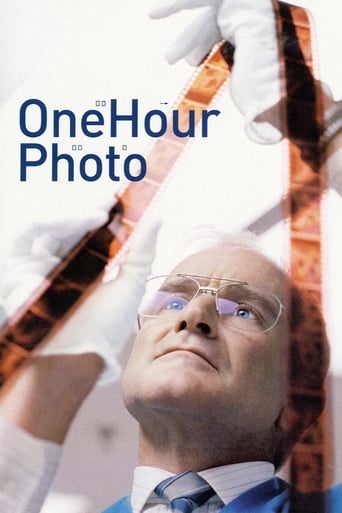

There is a specific subgenre of American cinema dedicated to the "One Bad Day"—that kinetic, suffocating narrative where a protagonist is stripped of their dignity layer by layer until civilization’s social contract no longer applies. In *STRAW*, Tyler Perry attempts to craft his own variation of *Falling Down* or *John Q*, but with a distinct, often polarizing frequency. Here, the vessel for this disintegration is Janiyah (Taraji P. Henson), a single mother whose descent is not just a thriller hook, but a operatic examination of the weight placed on Black womanhood. While Perry’s directorial hand remains as heavy and blunt as a sledgehammer, the film transcends its melodramatic machinery through a performance by Henson that feels less like acting and more like an exorcism.

To watch *STRAW* is to witness a stress test of the human spirit. Perry, who serves as writer, director, and producer, constructs Janiyah’s world as a claustrophobic cage of systemic failures. The visual language is stark, occasionally suffering from the flat, brightly lit aesthetic that plagues much of Perry’s Netflix output. However, in the film’s more chaotic moments—particularly the sudden, biblical downpours and the frenetic editing of the initial "bad day" montage—there is an effective, if unintentional, surrealism. The environment feels hostile by design, a universe conspiring to crush Janiyah between an eviction notice and a callous boss.

Yet, where the script often leans into caricature (the villainy of the supermarket manager is cartoonishly evil), Henson grounds the absurdity in a terrifying emotional reality. She plays Janiyah not as a victim, but as a exposed nerve. The film’s centerpiece—a standoff inside a bank that begins as a desperate attempt to cash a paycheck—is where the movie finds its pulse. It is here that Perry makes his most interesting choice: rather than focusing solely on the gun, he focuses on the gaze. The interaction between Janiyah and the bank manager, Nicole (played with surprising, quiet grace by Sherri Shepherd), shifts the film from a crime thriller to a chamber drama about shared trauma.

In these moments, the film deconstructs the "Angry Black Woman" trope by revealing the grief beneath the rage. The narrative’s major twist—that Janiyah’s motivation, her daughter Aria, has been a hallucination born of a psychotic break following the child’s death—recontextualizes the entire film. What initially plays as a frantic action movie is revealed to be a tragedy of mental health and unprocessed loss. While the execution of this reveal is jarring, perhaps even manipulative, it forces the audience to view Janiyah’s violence not as criminality, but as a symptom of a mind fracturing under an impossible load.

Perry’s direction often struggles to balance these tonal shifts, wavering between gritty social commentary and soap-opera theatrics. The "alternate ending" sequence, where we see Janiyah gunned down, feels like a cheap shock tactic before the "true" ending of peaceful surrender is allowed to play out. And yet, despite the clunky dialogue and the relentless misery, *STRAW* lands a resonant emotional punch. It succeeds not because of its craft, but because it gives space to a specific, often ignored anguish.

Ultimately, *STRAW* is a flawed vessel carried by a perfect storm of a performance. Henson demands that we look at Janiyah not as a statistic or a headline, but as a mother drowning in plain sight. It is a film that screams for attention—loud, messy, and undeniable.