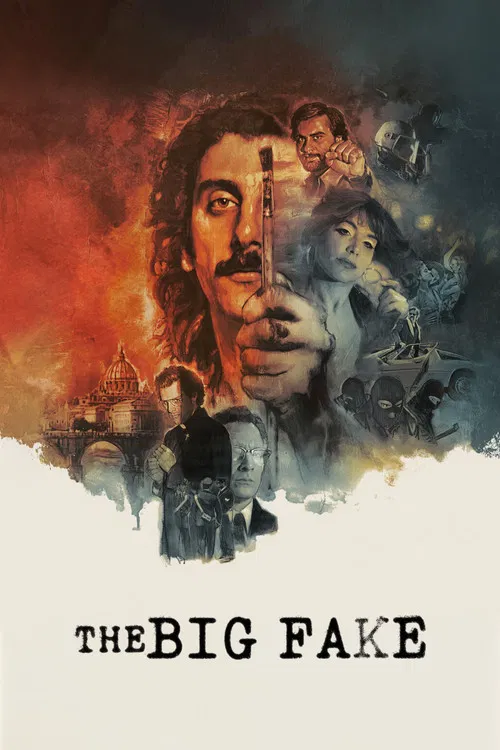

The Canvas of DeceitIn the hazy, cigarette-stained timeline of the Italian "Years of Lead," truth was often the first casualty. It was an era where the state and the insurrectionists engaged in a theater of violence so performative that reality itself felt staged. Into this fractured landscape steps Stefano Lodovichi’s *The Big Fake* (2025), a film that treats the act of forgery not merely as a crime, but as the only logical survival mechanism in a society that has lost its authentic center. By chronicling the life of Antonio "Tony" Chichiarelli—the painter-forger who infamously drafted the fake Red Brigades communiqué during the Aldo Moro kidnapping—Lodovichi moves beyond the standard biopic to offer a meditation on the power of the counterfeit.

The film does not merely recount events; it observes the texture of a lie. Lodovichi, whose previous work has often danced around the edges of psychological entrapment, here constructs 1970s Rome as a gallery of shadows. The camera lingers obsessively on the physicality of the medium: the mixing of pigments, the aging of canvas, the precise, terrifying stroke of a brush that mimics a master so well it mocks the original.

Visually, *The Big Fake* is suffocatingly beautiful. The cinematography avoids the sepia-toned nostalgia often reserved for period pieces, opting instead for a bruised color palette of sickly greens and charcoal greys. Lodovichi understands that for Toni, the studio is a sanctuary that slowly transforms into a prison. The most arresting sequences are not the high-stakes negotiations with the Magliana gang, but the silent, feverish moments of creation. When Toni works, the sound design drops the ambient noise of the city, leaving only the wet scrape of the palette knife—a sonic isolation that underscores his tragedy: he is a genius trapped in the margins, an artist whose masterpiece must remain unsigned to exist at all.

At the center of this tragedy is Pietro Castellitto, who delivers a performance of vibrating, nervous energy. He plays Toni not as a suave conman, but as a man deeply offended by the world’s refusal to recognize his legitimate talent. Castellitto captures the specific narcissism of the unappreciated artist; his eyes dart with a mixture of fear and arrogance. He makes us understand that for Chichiarelli, forging a de Chirico or a terrorist manifesto is the same act—it is an assertion of control over a reality that has rejected him. The forgery becomes a way to insert himself into history, a desperate scrawl of "I was here" on the walls of the establishment.

The film’s brilliance lies in its refusal to moralize the fake. In the narrative architecture of *The Big Fake*, the institutions—the government, the media, the galleries—are shown to be just as fraudulent as Toni’s paintings. When the fake Red Brigades communiqué is released, the film captures the terrifying absurdity of how quickly the lie is metabolized by the public. The "fake" becomes a historical agent, more powerful and consequential than the truth. Lodovichi suggests that in a corrupt system, the forger is the ultimate realist; he is the only one who understands that value is an illusion agreed upon by thieves.

Ultimately, *The Big Fake* is a melancholic diagnosis of modern Italy’s relationship with its own history. It posits that we are living in the downstream effects of these great deceptions. The film ends not with a bang, but with a lingering sense of unease, leaving the audience to question the authenticity of the narratives we consume today. It is a masterful, cynical, and deeply human work that reminds us that sometimes, it takes a lie to reveal the shape of the truth.