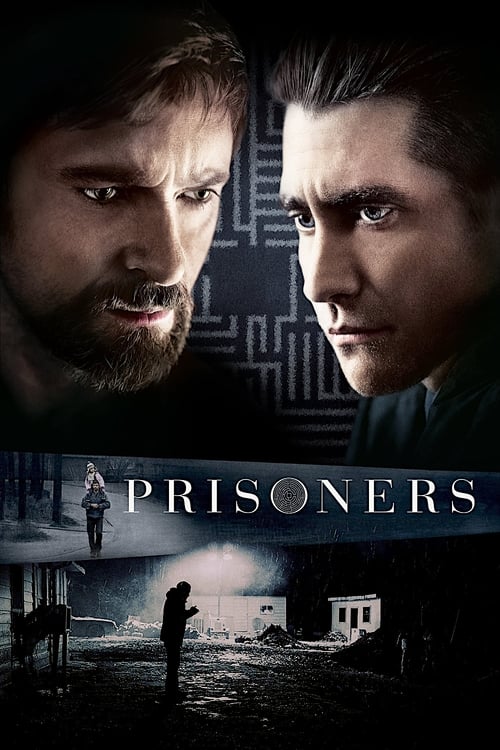

The Architecture of DespairThere is a specific kind of dread that permeates Denis Villeneuve’s *Prisoners*, a damp, heavy cold that seems to seep from the screen and settle into your bones. Released in 2013 as the French-Canadian director’s English-language debut, the film was initially marketed as a standard police procedural—a "missing child" thriller in the vein of *Taken* or *Ransom*. However, to view *Prisoners* through the lens of genre entertainment is to miss its terrifying point. This is not a film about a rescue; it is a film about the erosion of the soul. It is a moral horror story that asks how much of our humanity we are willing to amputate to save the things we love.

Villeneuve, fresh off the success of his scorched-earth tragedy *Incendies*, brought an outsider’s forensic eye to the American suburbs. He strips away the comfort of the middle-class cul-de-sac, revealing a landscape that is both banal and threatening. Working with legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins, Villeneuve constructs a visual world that is perpetually overcast. The Pennsylvania setting is rendered in a palette of slate greys, muddy browns, and bruised blues. It rains, it snows, and the slush on the ground seems to trap the characters in a physical purgatory. The camera does not sprint; it lingers, often observing the violence—or the aftermath of violence—with a detached, unblinking gaze that forces the audience to confront the ugliness without the anesthesia of quick cuts.

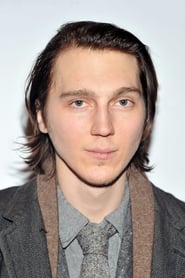

At the center of this moral labyrinth is Keller Dover, played with volcanic intensity by Hugh Jackman. Dover is a "prepper," a man who believes he can protect his family from any disaster if his basement is stocked and his will is strong. When his daughter is abducted, his entire worldview collapses. The systems he trusted fail him, and he decides that God has left the building. Jackman’s performance is terrifying because it is rooted in love; he becomes a monster fueled by a father’s primal instinct. His descent into vigilantism—specifically his torture of the intellectually disabled suspect Alex Jones (Paul Dano)—is the film’s central provocation. Villeneuve challenges us: We want the girl found, but can we stomach the cost? The film turns the audience into accomplices, testing our own ethical breaking points as Dover swings the hammer.

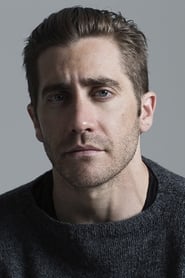

Counterbalancing Dover’s Old Testament fury is Detective Loki, portrayed by Jake Gyllenhaal. If Dover is pure, chaotic emotion, Loki is the embodiment of frustrated order. Twitchy, tattooed, and visibly exhausted, Loki is a man fighting a losing war against chaos. Gyllenhaal’s performance is a masterclass in internal acting; his eyes dart with the anxiety of a man who knows that "following the book" might not be enough. The tension between these two men—one operating outside the law, the other shackled by it—creates the film’s suffocating atmosphere. They are both trapped in the same maze, running in circles as the clock ticks down.

Ultimately, *Prisoners* is a film about the impotence of control. The "maze" mentioned throughout the film is not just a plot device; it is a metaphor for the intricate, confusing nature of grief and justice. Villeneuve refuses to offer the catharsis typical of Hollywood thrillers. Even when the mystery unravels, the resolution feels pyrrhic. The final shot—a faint whistle heard from the depths of the earth—is one of modern cinema’s most haunting endings. It hovers between hope and oblivion, leaving us in the dark, straining to hear a sound that might just be the wind. It is a masterful conclusion to a film that argues that while we may escape our prisons, we rarely escape ourselves.