The Pilgrim in the PorscheIn the peculiar ecosystem of Italian cinema, Checco Zalone functions less as a comedian and more as a national stress test. For nearly two decades, his collaborations with director Gennaro Nunziante have served as a funhouse mirror for the Bel Paese, reflecting its vices—nepotism, indolence, casual racism—back at the audience with a grin so disarming that the insult feels like a hug. With *Buen Camino*, the duo reunites after a nine-year hiatus, retreating from the sharper, more divisive political edges of Zalone’s solo directorial effort, *Tolo Tolo* (2020). The result is a film that trades the biting satire of the migrant crisis for the well-worn cobblestones of the Camino de Santiago, offering a journey that is safe, scenic, and undeniably comfortable.

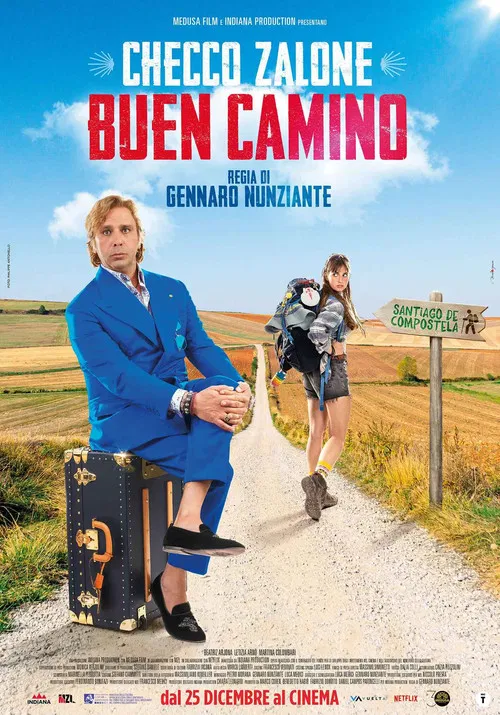

The premise is quintessential Zalone: Checco is the idle, wealthy son of a sofa magnate, a man whose existence is defined by pools, yachts, and a complete allergy to labor. When his daughter Cristal (named after the champagne, naturally) vanishes to find herself on the famous Spanish pilgrimage, Checco is forced to pursue her. Nunziante’s direction here remains steadfastly functional; he films comedy with the flat, bright lighting of a television commercial, ensuring that no shadow ever obscures a punchline. However, the setting forces a visual evolution. As Checco’s Ferrari—a gleaming red scar against the dusty, ochre landscapes of the Mesetas—gives way to walking boots, the film allows the grandeur of the Pyrenees to dwarfing its protagonist. The visual gag is obvious but effective: the grotesque excess of Italian materialism clashing against the ancient, ascetic spirituality of the pilgrim's trail.

At its heart, *Buen Camino* attempts to pivot from sociopolitical satire to a generational dramedy. The conflict isn't just between a rich man and a dirt road; it is between a Boomer/Gen-X father who equates love with financial provision, and a Gen-Z daughter seeking intangible "meaning." Zalone’s performance is, as always, a marvel of physical commitment. He plays the "ignorant Italian" with a specificity that saves it from caricature—his horror at the lack of luxury hotels, his transactional approach to spirituality. Yet, the emotional core feels somewhat engineered. The script, co-written by the duo, relies heavily on dismantling easy targets: the "radical chic" affectations of his ex-wife’s new circle and the performative asceticism of modern pilgrims. While Zalone’s character arc—learning that he cannot buy his daughter's affection—is sincere, it lacks the subversive danger of his previous work. The "monster" we loved to watch has been domesticated by fatherhood.

Ultimately, *Buen Camino* is a film of reconciliation rather than revolution. It avoids the polarization of *Tolo Tolo* in favor of a "buonismo" (a uniquely Italian term for feel-good moralizing) that reassures the audience rather than challenging them. It confirms that Zalone remains the last great mask of the Commedia dell'arte, capable of filling theaters in an era of streaming fragmentation. But one leaves the theater with the nagging sense that the pilgrimage was a bit too smooth. We laugh, certainly, but we are no longer implicated in the joke. Zalone has walked the path, but he hasn't quite lost his shoes.