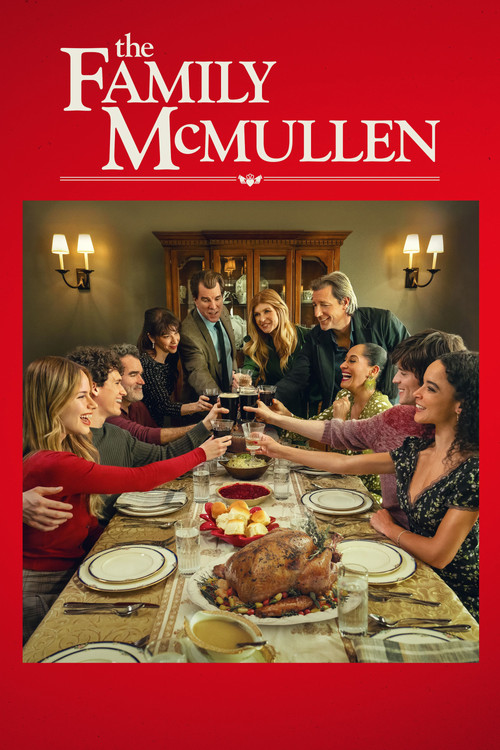

The Weight of Coming HomeIf the 1990s indie boom was a rebellion against polished studio gloss, Edward Burns’s *The Brothers McMullen* (1995) was its quietest insurgent—a $25,000 conversational piece about Irish-Catholic guilt that felt like eavesdropping on a neighbor. Three decades later, Burns returns to the well with *The Family McMullen* (2025), a film that asks a question terrifying to any nostalgic heart: can you go home again without finding the furniture rearranged and the lights a little dimmer? The answer, Burns suggests, is yes, but the comfort it offers is now tinged with the melancholy of time passed, not just time wasted.

Visually, Burns has abandoned the guerrilla grain of his debut for a polished, almost golden warmth that mirrors his career trajectory from indie darling to established veteran. The cinematography, rich with the amber hues of a stylized autumn in New York, wraps the characters in a visual embrace that feels undeniably cozy, perhaps to a fault. Gone are the jagged handheld shots of 20-somethings navigating Manhattan sidewalks; in their place are stable, composed wide shots of suburban living rooms and affluent kitchens. It creates an atmosphere that is less about the anxiety of "making it" and more about the stasis of having made it, only to realize you’re still lonely. The film’s aesthetic is comfortable, like a worn sweater, yet this polish occasionally threatens to rob the story of the raw, neurotic edge that made the McMullens so compelling in the first place.

At the heart of the film lies a study in generational friction. Barry McMullen (Burns), once the commitment-phobic cynic, is now a twice-divorced father projecting his own romantic failures onto his adult children. But the film’s emotional anchor is surprisingly not Barry, but Patrick (Michael McGlone) and Molly (Connie Britton). McGlone, reprising his role with a deepened, weary gravity, embodies a specific strain of Irish-Catholic guilt that has curdled into midlife paralysis. His scenes with Britton—whose character navigates the ghost of her late husband (the absent Jack)—possess a tenderness that transcends the script’s occasional sitcom-adjacent beats. When the film allows these two to simply sit and breathe in the silence of their shared history, it achieves a poignancy that feels earned, not manufactured.

Ultimately, *The Family McMullen* functions less as a groundbreaking piece of cinema and more as a cinematic reunion tour. It does not possess the hunger of the 1995 original, nor does it try to. Instead, it offers a reflection on the circular nature of family trauma—how we run from our parents’ mistakes only to sprint headlong into new versions of them. It is a film of gentle resignation rather than revelation. For those who grew up with the McMullens, this visit is a warm, if slightly too tidy, reminder that while we can’t stop the clock, we can at least choose who we waste our time with.