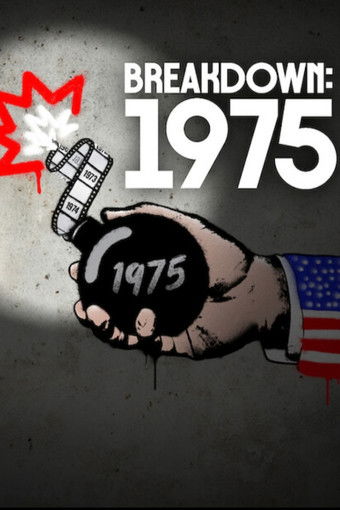

✦ AI-generated review

The Year America Cracked

There is a specific texture to the mid-1970s in America—a graininess that feels like a collective hangover. By 1975, the utopian dreams of the sixties had curdled into the paranoia of Watergate, the humiliation of Vietnam, and the grey stagnation of the economy. It was a time when the national psyche didn't just bruise; it fractured. Morgan Neville’s latest documentary, *Breakdown: 1975*, argues that this psychic fissure didn't destroy Hollywood—it liberated it. This is not a film about box office receipts; it is an autopsy of a moment when American cinema stared into the abyss and, for the first time, the abyss blinked back.

Neville, a documentarian known for finding the human pulse in pop culture (*Won’t You Be My Neighbor?*), here adopts a frenetic, collage-like aesthetic that mirrors the chaos of the era. He dispenses with the dry, Ken Burns-style historical plodding in favor of a sensory assault. The film’s visual language is less "history lesson" and more "mixtape," stitching together a dizzying array of clips that bleed the boundaries between fiction and reality.

One of the film’s most arresting visual arguments is a jarring, brilliant edit involving child actress Kim Richards. Neville cuts from her innocent, ice-cream-eating cherub in Disney’s *Escape to Witch Mountain* directly to her shocking, ice-cream-holding death in John Carpenter’s *Assault on Precinct 13*. It is a cruel, hilarious, and perfect encapsulation of the documentary’s thesis: the safety rails were gone. The innocence of the "family picture" had been assassinated, replaced by a ruthless, random violence that felt uncomfortably like the evening news.

Narrated with cool, detached intelligence by Jodie Foster—herself a child of this cinematic revolution—the film posits that the "New Hollywood" was a direct reaction to the collapse of moral authority. When the President is a crook and the war was a lie, the only honest response is the feral madness of *Taxi Driver* or the anarchic despair of *Dog Day Afternoon*.

However, Neville’s approach is not without its own chaotic flaws. Critics might note that the film plays fast and loose with the calendar. Oliver Stone, in a fervent interview, rattles off a list of "1975 masterpieces" that includes films from 1976, and the documentary happily blurs the lines, pulling in *Chinatown* (1974) and *Network* (1976) to suit its narrative. Yet, to nitpick the dates is to miss the point. *Breakdown: 1975* is capturing a vibe, not a spreadsheet. It reflects the delirium of a fever dream where time compresses under the weight of anxiety.

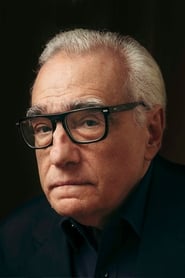

The film struggles slightly when it leans on younger talking heads like Seth Rogen, whose commentary, while appreciative, lacks the scar tissue of those who lived through the "breakdown." The emotional core is far stronger when we hear from the likes of Ellen Burstyn or Martin Scorsese, artists who speak of the era not as a cool retro aesthetic, but as a terrified struggle for meaning.

Ultimately, *Breakdown: 1975* leaves us with a haunting realization about our current cinematic landscape. It portrays a brief, shining window where the commercial and the artistic were not enemies, but desperate bedfellows. Neville shows us a Hollywood that was willing to risk everything because the world outside was already broken. It is a thrilling, if occasionally scattershot, reminder that cinema is at its most vital not when it offers an escape, but when it holds up a mirror to our own disintegration.