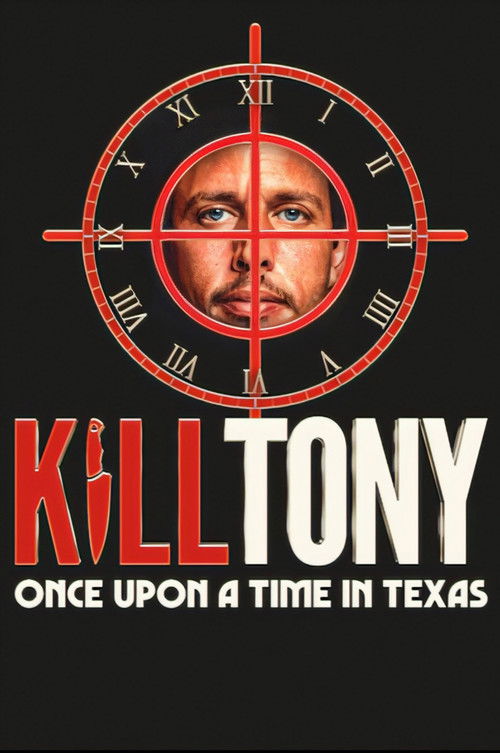

The Colosseum of CringeThere was a time when stand-up comedy was an intimate conspiracy—a secret shared between a performer and a dark, whiskey-soaked room. It was fragile. It was dangerous. In *Kill Tony: Once Upon a Time in Texas*, director Anthony Giordano and host Tony Hinchcliffe attempt to scale that fragility to the size of a Roman spectacle, and the result is a fascinating, if frequently discordant, crash of ambition against reality. This isn't just a comedy special; it is a gladiatorial exhibition where the lions are often the judges, and the Christians are terrified amateurs clutching a microphone like a lifeline.

The film (and make no mistake, this is a film about a live event, not just a recording) captures the "Kill Tony" phenomenon at its absolute zenith of excess. Moving from the claustrophobic intensity of the Comedy Mothership to the cavernous expanse of a Texas arena, the visual language shifts from underground punk rock to stadium pop. Giordano’s camera work emphasizes this vastness, frequently pulling back to show the lone bucket-pull comic as a speck of dust against a massive LED backdrop. The aesthetic is suffocatingly large, turning the simple act of telling a joke into a high-stakes tightrope walk over a pit of 15,000 screaming critics.

The central tension of *Once Upon a Time in Texas* lies not in the jokes themselves, but in the psychological warfare of the format. Hinchcliffe, presiding over the chaos like a sharp-suited Caesar, has assembled a panel of comedy royalty—Gabriel Iglesias, Rob Schneider, and the erratic Roseanne Barr. The dynamic is jarring. Iglesias, ever the professional, attempts to offer constructive warmth, while Barr serves as a chaotic element, her performance a fascinating study in unraveled celebrity. Her set, a rambling fixation on vulgarity without the structure of a punchline, provides the film's most uncomfortable, yet honest, moment: a legend stripping away the polish to reveal the raw, unpolished id underneath.

But the true narrative arc belongs to the "bucket pulls"—the random lottery that dictates the show's soul. When Timmy No Brakes takes the stage, we witness something transcending simple stand-up. His performance is a meta-commentary on the genre itself, a "4D chess" move where the character work is so committed it blurs the line between incompetence and genius. In these moments, the film shines. We aren't watching a polished routine; we are watching a human being gamble their dignity in real-time. The camera catches the sweat on their brow and the terror in their eyes, grounding the massive spectacle in a deeply human vulnerability.

However, the transition to this scale is not without its casualties. The intimacy that allows a roast to feel like "locker room talk" evaporates in an arena. The cruelty, usually playful in a club, echoes a bit too harshly here. When the panel "glazes" (over-praises) their peers while eviscerating a nervous newcomer, the power imbalance feels less like mentorship and more like bullying. The sound design struggles to reconcile the intimate audio of the mic with the delayed roar of the crowd, creating a slight disconnect that alienates the viewer at home. We are voyeurs to a party that got too big for the house.

Ultimately, *Kill Tony: Once Upon a Time in Texas* is a document of modern comedy's identity crisis. It tries to be both an underground fight club and a polished Netflix variety hour. While the narrative occasionally collapses under the weight of its own self-importance, and the "roasting" sometimes sours into mere meanness, the experiment remains compelling. It forces us to ask what we want from comedy: the safety of a prepared script, or the exhilarating, cringe-inducing possibility that the person on stage might fail spectacularly? Hinchcliffe bets on the failure, and in doing so, creates a piece of art that is as exhausting as it is electric.