Stumbling in Another Man’s ShoesCinema is often a study of trajectory, not just for the characters on screen, but for the artists behind the camera. In 2014, director Tom McCarthy was undeniably one of American independent cinema’s most humanistic voices. With films like *The Station Agent* and *The Visitor*, he had established a reputation for quiet, observational dramas that treated loneliness with profound dignity. It is this pedigree that makes *The Cobbler* not merely a failure, but one of the most baffling anomalies in modern film history. Released just a year before McCarthy would achieve cinematic immortality with the Oscar-winning *Spotlight*, this magical realist fable collapses under the weight of an identity crisis far more severe than the one suffered by its protagonist.

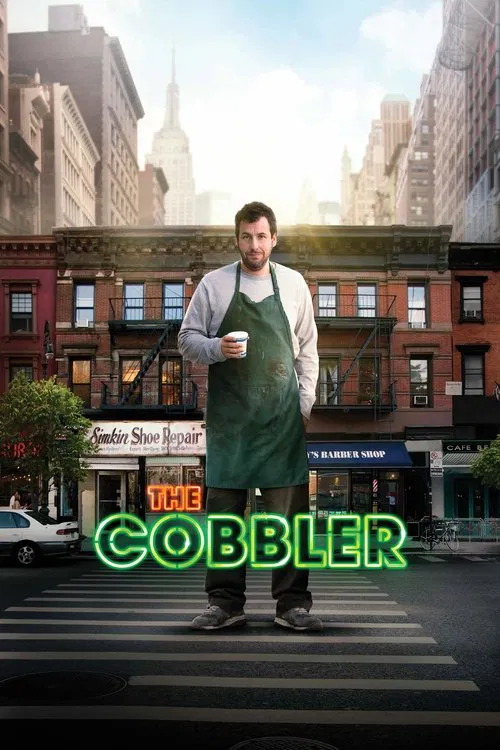

The premise suggests a modern fairy tale, rooted in the fading texture of the Lower East Side. Max Simkin (Adam Sandler) is a fourth-generation cobbler, grinding out a meager existence in a shop that feels less like a business and more like a tomb of family obligation. The film’s visual language, initially, is promising. McCarthy captures the dust motes and the worn leather of Max’s shop with a nostalgic warmth, suggesting a world where craftsmanship still holds magical potential. When Max discovers an ancestral stitching machine that allows him to physically transform into his customers by wearing their shoes, the stage is set for a parable about empathy. We expect Max to learn what it means to live another life, to understand the burdens of his neighbors.

However, the film violently rejects this empathetic potential in favor of a tonal dissonance that is almost impressive in its miscalculation. Instead of using his gift for connection, Max uses it for voyeurism, petty theft, and uncomfortable deception. The narrative veers sharply from a whimsical fable into a gritty, unpleasant crime drama involving slumlords and gang violence. The visual palette shifts from the warm amber of the shop to the harsh, gray chill of urban decay, but the transition feels unearned. We are watching a protagonist who behaves with a sociopathic detachment, yet the score and direction insist we view him as a lovable schlub.

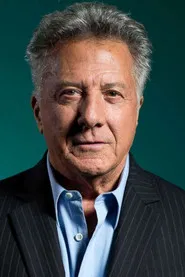

Adam Sandler, an actor capable of tremendous depth when given the right material (*Punch-Drunk Love*, *Uncut Gems*), delivers a performance of heavy-lidded exhaustion. He plays Max not as a man discovering wonder, but as a man burdened by it. There is a specific sequence where Max impersonates his own missing father (Dustin Hoffman) to comfort his dying mother. In the hands of a different director, this might have been a moment of transcendent sweetness. Here, it plays out with a morbid, uncanny quality—a deception that feels less like a gift and more like a violation of the natural order. It encapsulates the film’s core failure: it mistakes invasion of privacy for intimacy.

The film’s ultimate undoing, however, is its conclusion. In a desperate attempt to expand the mythology, the narrative spirals into a bizarre suggestion of a secret society of cobblers, hinting at a wider universe of magical tradesmen. It is a jarring pivot to superhero tropes that feels alien to the intimate, indie aesthetic McCarthy is known for. It cheapens the emotional stakes, suggesting that Max’s journey wasn’t about self-discovery, but about lineage and destiny.

*The Cobbler* remains a fascinating artifact—a "blimp crash" of a movie that occurred right before its captain steered the ship to the Oscars. It serves as a reminder that even the most empathetic directors can lose their way when they prioritize high-concept mechanics over the messy, authentic truth of human behavior. Max Simkin walked a mile in many shoes, but the film never quite figured out how to stand on its own two feet.