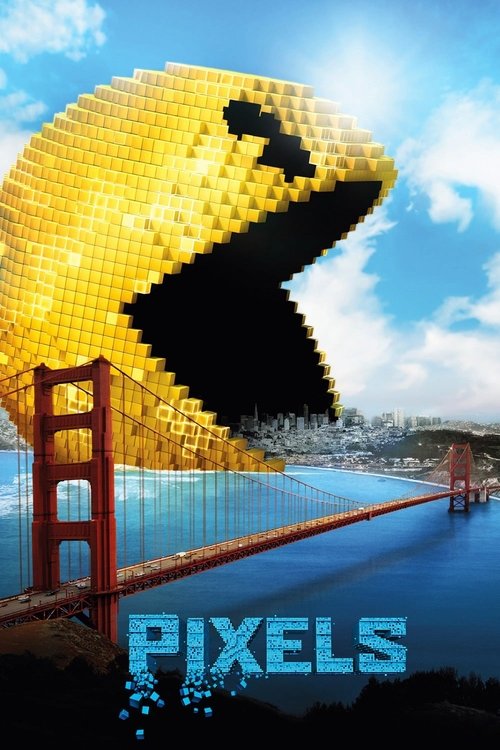

The Cynicism of MemoryNostalgia is a potent, dangerous currency in modern cinema. In the hands of a filmmaker like Spielberg, it is weaponized to evoke wonder; in the hands of the Happy Madison machine, it is too often reduced to a transaction. *Pixels* (2015), directed by Chris Columbus, stands as a fascinating, if depressing, monument to this latter approach. It attempts to adapt Patrick Jean’s brilliant, surreal 2010 short film—a two-minute abstract masterpiece where 8-bit logic consumes New York—into a conventional blockbuster narrative. The result is a film that misunderstands the very subculture it claims to celebrate, transforming the abstract joy of play into a literal, and surprisingly cynical, war for survival.

The premise is undeniably "high concept": aliens, misinterpreting 1982 arcade feeds as a declaration of war, attack Earth using video game models. It’s *Ghostbusters* for the Atari generation. Yet, where the short film was an aesthetic experiment, the feature film is a vehicle for the "Sandler Archetype"—the underachieving man-child who is secretly superior to the changing world around him.

Visually, Columbus—a director capable of genuine magic (*Home Alone*, *Harry Potter*)—achieves a strange technical victory amidst the tonal wreckage. The film’s "voxels" (volumetric pixels) are luminous and tactile. When Pac-Man chomps through a New York street, turning asphalt and fire trucks into cascading cubes of light, the effect is hypnotic. There is a weightlessness to the destruction that is almost beautiful, stripping the violence of its gore and replacing it with a digital sterility. However, this visual flair is constantly at war with the film’s flat, televisual direction. The camera rarely participates in the game; it merely observes Adam Sandler observing the game, creating a distance that fataly undermines the stakes.

The film's central failure, however, lies in its heart—or lack thereof. *Pixels* operates on a defensive, almost hostile form of nostalgia. The protagonists, led by Sandler’s Sam Brenner, are not just "nerds"; they are martyrs of a bygone era, demanding that the present day apologize for moving on. The script conflates gaming skill with moral superiority, suggesting that the ability to memorize patterns in *Galaga* is a more valid life skill than military strategy or political nuance.

This resentment is most palpable in the film's treatment of its characters. The dynamic between the "Arcaders" and the rest of the world is not one of misunderstood outcasts finding redemption, but of entitled experts waiting to say "I told you so." The film’s gender politics are particularly retrograde, treating Michelle Monaghan’s Violet—a high-ranking military officer—as a prize to be won by Brenner, provided she first acknowledges that his fixation on 1982 makes him the alpha male. It turns the inclusive, imaginative space of the arcade into a gated community of male grievance.

Even the finale, a recreation of *Donkey Kong* played out on a massive architectural scale, feels less like a climax and more like a checklist. We see the barrels, we see the hammer, but we do not feel the *play*. In adapting a medium defined by interactivity into a passive viewing experience, Columbus misses the fundamental appeal of video games: the agency of the player.

Ultimately, *Pixels* is a film that hates the present as much as it fetishizes the past. It takes the bright, abstract innocence of early gaming—where a yellow circle could be a character and a few beeps could be a symphony—and crushes it under the weight of a bloated, cynical studio formula. It is a "Game Over" screen that lasts for 106 minutes, leaving the viewer not with a sense of fun, but with the hollow realization that they have just watched someone else play a bad game very slowly.