The Arrows of History, Blunted by AmbitionEvery generation gets the Robin Hood it deserves, or perhaps, the one it fears it needs. If Errol Flynn gave us a Technicolor swashbuckler to laugh away the Depression, and Kevin Costner offered a brooding Gen-X crusader, the 2025 MGM+ adaptation of *Robin Hood* presents a hero for an era of deep political polarization and class warfare. Yet, in its rush to be the "grounded" and "gritty" corrective to the myth, showrunners Jonathan English and John Glenn have crafted a series that feels paradoxically weightless—a beautifully shot, violently earnest saga that struggles to find the human pulse beneath its chainmail.

From the opening frames, the series labors to distinguish itself from the green-tights nostalgia of the past. This is 12th-century England treated not as a fairytale backdrop, but as an occupied state. The central tension here is the suffocating Norman boot on the Saxon neck. Jack Patten’s Rob is not a displaced lord, but a forester’s son, a man born into the mud rather than merely adopting it. This class consciousness is the show's most intriguing gambit. The camera lingers on the disparity between the cold, stone brutality of the Norman keeps and the organic, chaotic life of the Saxon villages. We are meant to feel the occupation in the texture of the clothing and the scarcity of the food.

However, the visual language often betrays this gritty ambition. The cinematography is sweeping, utilizing the Serbian landscapes to stand in for a mythical Nottingham, yet there is a distractingly modern sheen to the production. The costumes are too clean, the teeth too white, the forests too perfectly dappled with "magic hour" light. It suffers from the "streaming epic" syndrome—a desire to look like *Game of Thrones* without the lived-in grime that made Westeros feel historical. When Rob draws his bow, the action is kinetic and visceral, but one rarely fears for his safety; he moves with the invulnerability of a superhero rather than the desperation of an outlaw.

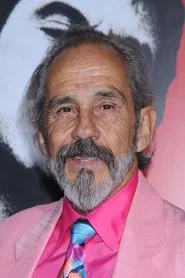

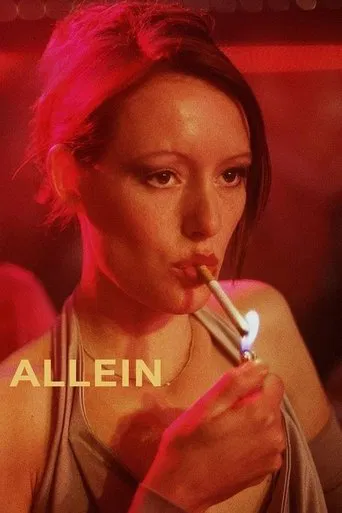

The series finds its surest footing not in the forests, but in the corridors of power, largely thanks to a casting coup: Sean Bean as the Sheriff of Nottingham. Bean, an actor who has died a thousand on-screen deaths, plays the Sheriff not as a mustache-twirling villain, but as a pragmatic bureaucrat of violence. He is weary, dangerous, and utterly captivating. Against him, Lauren McQueen’s Marian is a refreshing evolution. No longer a damsel, she is an infiltrator, a spy within the Norman court whose agency drives the plot as much as Rob’s arrows. The chemistry between Patten and McQueen is palpable, anchoring the show’s emotional stakes even when the political maneuvering becomes repetitive.

There is a specific sequence in the mid-season that captures the show's potential and its frustration. A Saxon wedding—a pagan rite held in defiance of the church—is interrupted by Norman soldiers. The ensuing violence is not swashbuckling; it is brutal and abrupt. It’s a moment that forces the audience to confront the reality of insurgency. Yet, moments later, the show retreats into standard action beats, undercutting the tragedy with stylized combat that feels designed for a trailer rather than a narrative.

Ultimately, this *Robin Hood* is a series at war with itself. It yearns to be a serious historical drama about colonization and resistance, echoing the complexities of *Vikings* or *The Last Kingdom*. But it cannot quite let go of the populist myth-making required by its title. It wants to deconstruct the legend while simultaneously relying on it. Jack Patten gives us a Rob who is stoic and physically capable, but the script rarely lets us see the doubt behind the eyes of a man asking his friends to die for a symbol.

As the first season concludes, we are left with a competent, entertaining, but largely safe reimagining. It strikes the target, certainly, but it fails to split the arrow. In trying to ground the legend in dirt and blood, the showrunners have forgotten that what makes Robin Hood endure isn't the realism of his struggle, but the romance of his impossible hope.