✦ AI-generated review

A Baroque Descent into Hell

In the landscape of modern action cinema, where chaos is often confused with excitement and shaky camerawork disguises a lack of choreography, *John Wick: Chapter 2* (2017) stands as a piece of defiant, crystallized architecture. If the first film was a gritty, emotional reaction—a man grieving a dog—this sequel, directed solo by Chad Stahelski, is a cold, calculated meditation on the nature of the killer. It is less a movie about revenge than it is a tragedy about a man realizing he is the architect of his own damnation.

Visually, the film abandons the scuzzy, wet-pavement noir of its predecessor for something far more operatic. Cinematographer Dan Laustsen paints the screen in neon blues and demonic reds, turning New York and Rome into mythological realms rather than habitable cities. This is nowhere more evident than in the film's centerpiece: the "Reflections of the Soul" exhibit in a modern art museum. Here, John Wick (Keanu Reeves) engages in a gunfight amidst a labyrinth of mirrors. It is a sequence that explicitly quotes Orson Welles’ *The Lady from Shanghai* and *Enter the Dragon*, but Stahelski repurposes the homage for a darker thematic point. As Wick shatters glass to kill his enemies, he is literally destroying his own reflection over and over again. The violence is not just kinetic; it is self-immolating. The pristine, high-culture setting clashes violently with the "low art" of the headshot, forcing the audience to acknowledge the aesthetic beauty we find in brutality.

Narratively, the film replaces the emotional impetus of the first chapter with a bureaucratic nightmare. The plot is driven by a "Marker"—a blood oath that forces Wick out of retirement to kill for Santino D'Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio). This device strips Wick of his agency. He is no longer an angry husband seeking retribution; he is a slave to the "rules" of a secret society that values protocol over morality. The tragedy of John Wick is not that he is a killer, but that he is *only* a killer. Every attempt he makes to return to the civilian world is rejected by the universe. He is a Sisyphus with a semi-automatic, pushing the boulder of his past up a hill, only to watch it roll back down in the form of a new contract.

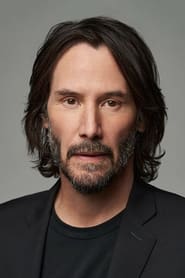

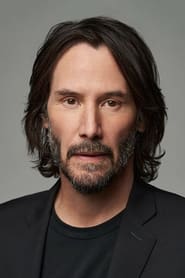

Reeves, often unfairly maligned for his limited range, finds a profound physical eloquence here. His performance is nearly silent, evoking the physical comedy of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, if those men dealt in death rather than pratfalls. The way he reloads a weapon or checks a chamber is not just technical proficiency; it is the weary muscle memory of a man who wishes his hands knew how to do anything else.

The film concludes not with a triumph, but with a terrifying expansion of scope. Wick breaks the one cardinal rule—killing on the grounds of the Continental Hotel—and is declared "excommunicado." The final shots, featuring Wick running through Central Park as every bystander turns to watch him, transform the genre from action to paranoia thriller. The world has not just turned against him; the world *is* the enemy. In expanding the mythology, Stahelski traps his hero in a gilded cage of infinite size. *John Wick: Chapter 2* proves that the only thing more dangerous than a man with nothing to lose is a man who realizes he never had anything to keep.