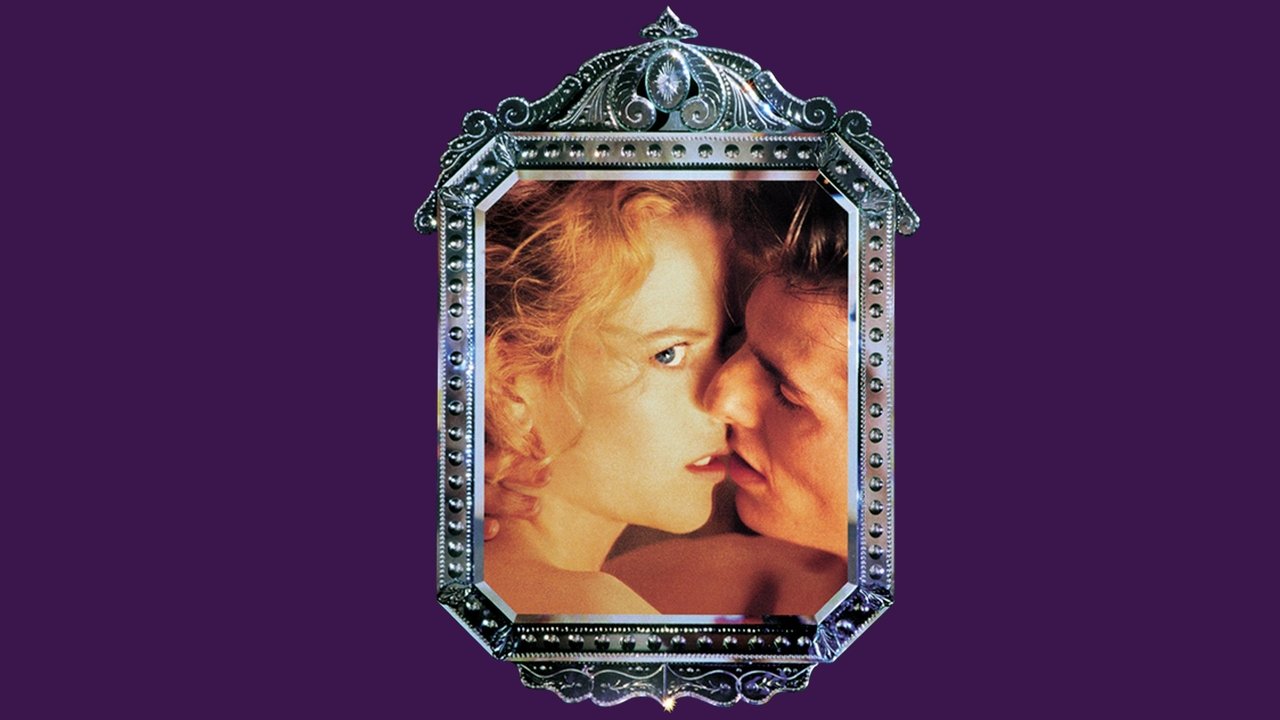

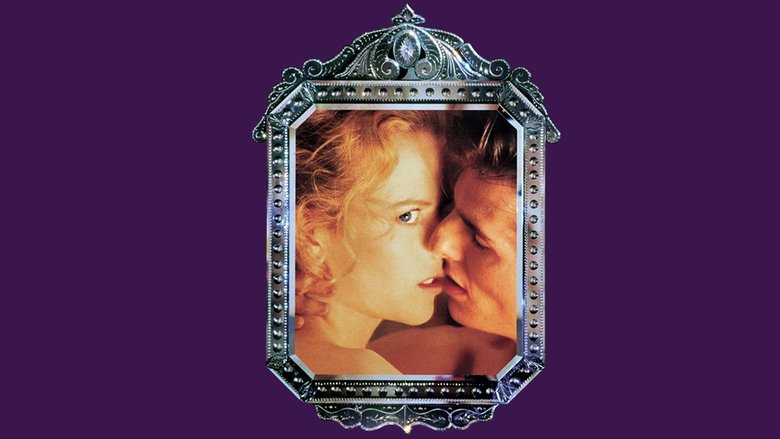

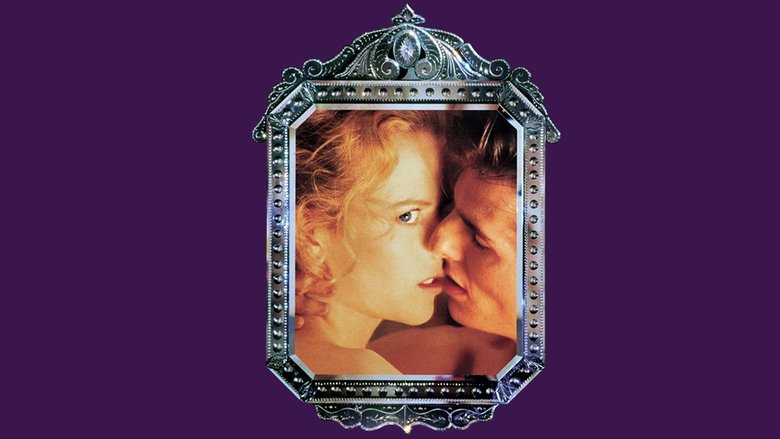

The Dream of WakingStanley Kubrick’s final cinematic gesture is not a period, but an ellipsis. Released posthumously in 1999, *Eyes Wide Shut* was initially misdiagnosed by a marketing machine desperate to sell it as a steamy, star-studded erotic thriller. Decades later, stripped of the tabloid noise surrounding its then-married stars, Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, the film reveals itself as something far colder and more terrifying: a ghost story about the unknowability of the person sleeping next to you. It is a film that suggests the "safety" of upper-middle-class domesticity is a thin sheet of ice over a dark, drowning ocean.

Kubrick, shifting Arthur Schnitzler’s novella *Traumnovelle* from fin-de-siècle Vienna to a dream-logic version of 1990s New York, constructs a city that feels deliberately artificial. This is not the gritty, breathing Manhattan of Scorsese; it is a soundstage purgatory, bathed in the sickly, omnipresent glow of Christmas lights that appear in nearly every frame. These lights do not signify holiday warmth but rather a suffocating consumer ritual, a constant reminder of the transactional nature of the world Dr. Bill Harford (Cruise) inhabits. The visual language is hypnotic and disorienting, using high-contrast colors—deep blues of the night conflicting with the garish golds of the wealthy interiors—to blur the line between Bill’s waking life and the lucid nightmare he stumbles into.

At the narrative’s hollow center is Bill’s shattered ego. The film’s inciting incident is not the masked ball, but a quiet, marijuana-hazed conversation in a bedroom. When Alice (Kidman) confesses her phantom desire for a naval officer she barely met—a desire so potent she would have abandoned her entire life for it—Bill’s reality fractures. Cruise delivers a performance of remarkable restraint; he plays Bill not as a hero, but as a naive tourist in the world of human desire. His subsequent "odyssey" through the night is a pathetic attempt at revenge, a search for an experience that can equal his wife’s fantasy. Yet, at every turn—from the grieving daughter of a patient to the chilling indifference of the Rainbow Fashions costume shop—he is rebuffed, exploited, or confused.

The famous orgy sequence, often discussed for its explicit nature, is actually a scene of profound anti-eroticism. It is a display of power, not pleasure. As Bill wanders through the Venetian-masked elite, the film pivots from a marital drama to a scathing critique of class. Bill, a successful doctor, realizes he is merely "hired help" to the truly wealthy. The masks strip away humanity, revealing the cold machinery of a society where people are commodities to be used and discarded. The terror of *Eyes Wide Shut* is the realization that the secret society isn't just a cult in a mansion; it is the operating system of the world Bill lives in, a system he foolishly thought he controlled.

Ultimately, Kubrick leaves us with a resolution that is as fragile as it is necessary. When the mask appears on the pillow next to a sleeping Alice, the dream logic invades the sanctuary of the home. The final scene in the toy store, surrounded by the gross excess of Christmas shopping, ends with perhaps the most famous final line in cinema history. It is not a vulgar joke, but a desperate prescription. To survive the abyss they have glimpsed, Bill and Alice must retreat into the only reality they can touch: the physical, the immediate, and the flawed present. They are awake, but they will never sleep soundly again.