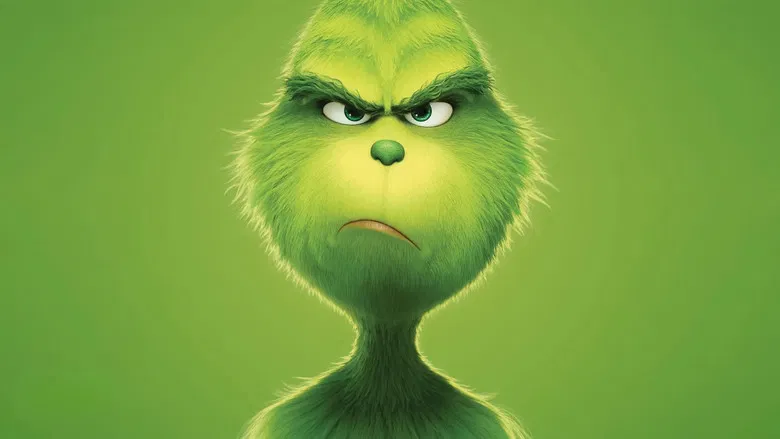

The Architecture of EmpathyIf cinema is a mirror held up to society, then our evolving interpretations of *The Grinch* reveal a fascinating shift in how we process antisocial behavior. In 1966, Chuck Jones gave us a slinking, termite-infested villain who was simply "a mean one." In 2000, Jim Carrey transformed him into a chaotic byproduct of consumerist trauma. But in Yarrow Cheney and Scott Mosier’s 2018 animated iteration, the green mountain-dweller is neither a monster nor an anarchist. He is, distinctly and painfully, a depressive neurotic. This film, glossy with the high-sheen finish of Illumination Entertainment, fundamentally softens the edges of Dr. Seuss’s jagged masterpiece, trading the original’s bite for a warm, if somewhat suffocating, hug.

Visually, the film is a triumph of texture over terror. Whoville has never looked more inviting—it is a confectionary dreamscape of gingerbread architecture and impossible physics, rendered with the kind of caloric density that makes you feel as though you’ve eaten a box of sugar cookies just by looking at it. The directors utilize the "Illumination House Style"—rubbery character designs and kinetic, slapstick energy—to create a world that feels physically safe. Even the Grinch’s lair, traditionally a damp cave of misery, is reimagined here as a marvel of introverted engineering. His gadgets are not rusty instruments of malice but convenient life-hacks for the socially anxious. The visual language suggests that the Grinch isn't rejected by Whoville because he is scary, but because he has voluntarily opted out of their aggressive joy.

Benedict Cumberbatch’s vocal performance is the fulcrum upon which this softer interpretation pivots. Abandoning his natural baritone for a pinched, nasal American accent, Cumberbatch plays the Grinch not as a villain, but as a man exhausted by the world. His irritation with the Whos feels less like misanthropy and more like sensory overload. This recontextualization is most evident in the film’s treatment of Cindy Lou Who. No longer just a plot device to prick the Grinch's conscience, she is given a subplot about an overworked single mother that mirrors the Grinch’s own isolation. The film posits that loneliness is the great equalizer—Cindy Lou feels it in her mother’s absence, and the Grinch feels it in his self-imposed exile.

However, this psychological leveling comes at a cost. By smoothing out the Grinch’s edges, the film robs his eventual redemption of its gravitational force. When a monster’s heart grows three sizes, it is a miracle; when a grumpy neighbor’s heart grows, it is merely a mood swing. The narrative tension collapses because the stakes have been lowered from "spiritual rot" to "holiday blues." The "heist" sequence, beautifully animated as it is, lacks the manic danger of the 1966 original or the unhinged frenzy of the Carrey version. It plays out with the precision of a silent comedy, efficient but toothless.

Ultimately, this version of *The Grinch* is a film for a generation that values emotional safety above all else. It is a technically dazzling, perfectly competent piece of family entertainment that refuses to let its protagonist be truly bad, and in doing so, prevents him from becoming truly good. It is a Christmas card that has been spell-checked, color-corrected, and sanitized of all ink smudges—beautiful to look at, but lacking the messy, human handwriting that makes a greeting feel sincere.