The Death of the Gentleman SpyIn 2006, the cinematic world was not asking for another James Bond; it was actively mourning the idea of him. The franchise had bloated into self-parody, a cavalcade of invisible cars and ice palaces that felt like relics of a bygone, less cynical era. Into this exhaustion stepped Daniel Craig—blonde, craggy, and looking more like a dockworker than a diplomat—facing a pre-release vitriol that seems quaint in hindsight. Yet, Martin Campbell’s *Casino Royale* did not just silence the "CraigNotBond" detractors; it dismantled the entire mythos of the gentleman spy, rebuilding him from the blood and bone up. This is not a film about saving the world; it is a film about the cost of killing a man.

Campbell, who had already saved the franchise once with the sleek *GoldenEye*, here opts for a visual language of brutality over elegance. From the opening black-and-white sequence, the film establishes a new thesis: violence is ugly, messy, and physically exhausting. When Bond earns his "00" status, it is not through a laser-watch gadget or a witty quip, but through a suffocating, desperate brawl in a bathroom where tiles shatter and life is choked out with agonizing slowness. Bond is no longer a superhero in a tuxedo; he is, as M so perfectly articulates, a "blunt instrument."

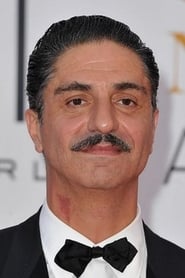

The film’s brilliance lies in how it treats action as character development rather than spectacle. Consider the Madagascar parkour chase. The bomb-maker Mollaka moves with fluid grace, leaping through vents and over obstacles like a dancer. Bond, by contrast, crashes through drywall like a bull. He doesn't finesse the environment; he destroys it. This physical clumsiness—the ego of a young agent who believes he is invincible—is mirrored in the poker scenes. The high-stakes Texas Hold'em game in Montenegro is shot with the same sweaty intensity as the gunfights. Bond loses not because of bad luck, but because of his arrogance. Le Chiffre, played with a terrifying, weeping-eyed stillness by Mads Mikkelsen, is not a megalomaniac engaging in world domination, but a desperate terrorist financier trying to cover his own bad debts. The stakes feel suffocatingly real because they are personal, not geopolitical.

However, the true subversive power of *Casino Royale* resides in its dismantling of the "Bond Girl" archetype through Vesper Lynd (Eva Green). Vesper is not a trophy to be won; she is the architect of Bond's soul. The film’s emotional centerpiece is not a bedroom conquest, but a fully clothed moment in a shower, where Bond holds a trembling Vesper as she washes the blood off her hands. It is a scene of profound intimacy that exposes Bond’s desperate desire for normalcy. He is ready to quit, to throw away the license to kill for a life of quiet anonymity. The tragedy of the film is that we, the audience, know this is impossible. We are watching a man open his heart only so it can be calcified into the armor worn by the Sean Connery and Roger Moore iterations.

By the time the credits roll, the transformation is complete. The "Bond, James Bond" catchphrase is finally uttered, but it doesn't sound like a charming introduction anymore. It sounds like a threat. *Casino Royale* stripped away the camp and the comfort, leaving us with a portrait of a man who had to kill his own humanity to become the weapon his country required. It remains the gold standard of modern blockbusters—a film that dared to ask not just how 007 fights, but why he bleeds.