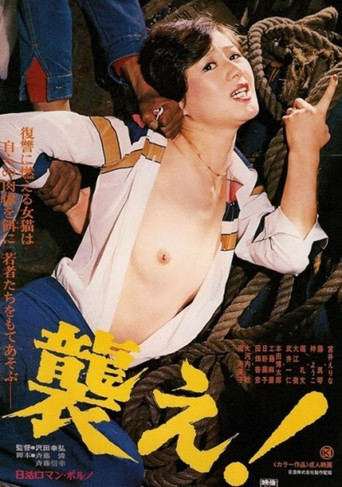

The Architecture of DesireThere is a fascinating paradox at the heart of Akihiko Shiota’s *Wet Woman in the Wind* (2016). Commissioned by the legendary Nikkatsu studio to celebrate the 45th anniversary of their "Roman Porno" line, the film operates under strict, almost algorithmic constraints: a runtime of roughly 80 minutes and a mandate for a sex scene every ten minutes. In lesser hands, this would result in a mechanical assembly of flesh and friction. However, Shiota, a director who has spent decades exploring the fragile boundaries of human connection in films like *Harmful Insect* and *Moonlight Whispers*, treats these constraints not as shackles, but as a poetic structure—a sonnet of softcore absurdity.

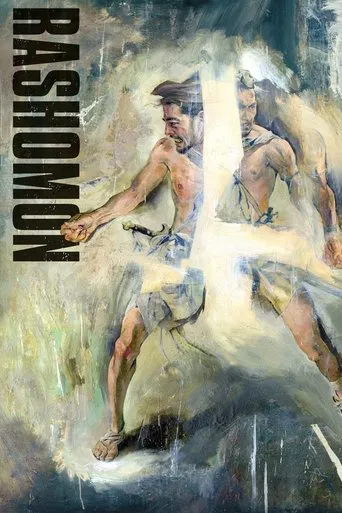

The premise is deceptively simple, echoing the screwball comedies of Howard Hawks as much as the pink films of the 1970s. Kosuke (Tasuku Nagaoka), a playwright suffering from a sophisticated form of burnout, has retreated to a mountain shack to embrace celibacy and silence. His monastic existence is shattered by Shiori (Yuki Mamiya), a café waitress and self-proclaimed "love hunter" who operates with the destructive energy of a natural disaster.

Visually, Shiota eschews the glossy, sanitized look of modern erotica for something earthier and more kinetic. The camera is often low and wide, capturing the lush, damp greens of the Japanese countryside which threaten to swallow the characters whole. The sound design is equally deliberate; the "wind" in the title is a constant auditory presence, a rushing force that mirrors Shiori’s relentless momentum. When she literally crashes her bicycle into the sea just to capture Kosuke’s attention, the splash is not just a physical gag—it is a baptismal announcement of chaos entering a closed system.

What elevates *Wet Woman in the Wind* above mere titillation is its astute subversion of gender dynamics. In traditional Roman Porno, women were often passive vessels for male frustration. Here, Shiota flips the script with glee. Shiori is not a victim, nor is she a manic pixie dream girl designed to save the protagonist. She is a predator, a force of nature who views Kosuke’s resistance as a structural challenge rather than a moral stance.

The film’s "heart" beats loudest in a scene involving an acting exercise. Kosuke, slipping back into his role as a director, tries to regain dominance by instructing Shiori on how to emote. It is a brilliant sequence where the lines between artistic direction and sexual power play blur indistinguishably. They scream, they grapple, and they engage in a physical dialogue that is far more intimate than the mandated sex scenes. The nudity becomes almost secondary to the raw, unvarnished exposure of their egos. Shiota suggests that the true obscenity isn't the act of sex, but the terrifying vulnerability of needing another person.

Ultimately, *Wet Woman in the Wind* succeeds because it refuses to take its own genre too seriously, while taking its characters’ neuroses very seriously. It is a film about the impossibility of control—how we try to curate our lives into quiet, manageable narratives, only for life (in the form of a wet, chaotic woman) to crash through the wall. Shiota has crafted a work that is undeniably erotic, but also deeply funny and strangely human. It reminds us that desire is rarely dignified; it is a messy, undignified, and vital collision that leaves us, like Kosuke, shivering in the wind.